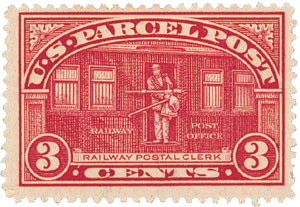

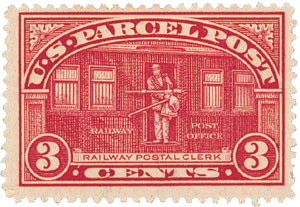

# Q3 - 1913 3c Parcel Post Stamp - Railway Post

City: Washington, DC

Printing Method: Engraved

Perforations: 12

Color: Carmine

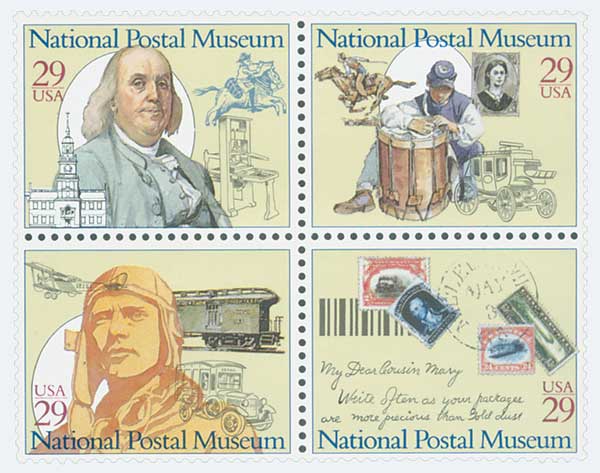

Railway Mail

On July 7, 1838, Congress approved an act that declared all United States railroads as post roads. This would lead to a dramatic increase in the use of railroads to deliver mail.

In the 1830s, businesses and individuals began to complain that mail delivery was too slow. At the time, it was carried by horse and stagecoach.

The postmaster general answered these calls by authorizing mail to be put on trains in the early 1830s. The first mail carried by train was delivered on December 5, 1832, aboard a train between Lancaster and West Chester, Pennsylvania.

The next major development came in May 1837, when John E. Kendall was made a route agent, marking the first time a clerk was appointed to accompany the mail on a railroad car. When the mail traveled on these trains, it usually sat unopened, waiting to be sorted at the local office.

To improve service, on July 7, 1838, Congress passed an act declaring all US railroads to be post roads. This act helped increase the use of railroads for mail delivery. It also led to a significant decrease in the use of post riders and horse-drawn vehicles. However, they were still used to deliver to post offices that weren’t along railway routes. In areas of the country that didn’t have railroads, contractors delivered the mail and were called star routes.

For nearly 30 years, trains were used to transport mail between post offices. The mailbags were loaded onto the trains and delivered to the post office where they were sorted. However, while some of the mail was delivered, many letters were returned to the bags and placed back on the trains to be sorted later. Several issues also arose. The post office and the railroads struggled to agree on a fixed rate for mail transported by rail. In some cases, this led to railroads refusing to deliver the mail. The post office felt the railroads were beyond their control and started to consider other options.

Soon the idea emerged to have mail clerks on the trains to sort the mail as it traveled between towns. In 1862, the idea was briefly tested on the Hannibal and St. Joseph line in Missouri. Then two years later, Chicago’s Assistant Postmaster George B. Armstrong pushed for the widespread use of a railway post office and succeeded. The first mail car, a renovated baggage car, ran on the Chicago and North Western Railroad line between Chicago and Clinton, Iowa, on August 28, 1864.

Clerks aboard the train sorted mail not just for routes along the line, but also for those beyond the end of the line. This new railway mail service proved a great success. More mail cars were added to travel between New York and Washington, New York, and Erie, Pennsylvania, as well as between Chicago and Burlington, Illinois, and Chicago and Rock Island, Illinois.

These trains didn’t always stop at every station, but those smaller stations still had mail. Early on, the trains had to slow down immensely so the clerks could grab the mailbags, which was both inefficient and dangerous. Eventually, they developed mail cranes. Mailbags were hung on a crane at stations that were too small for the train to stop. The clerk used a metal mar to grab the bag as the train passed at about 70 miles per hour.

By 1867, there were 18 railway mail routes that crossed over 4,435 miles of track with 160 clerks hard at work. They were so efficient that dozens of clerks at stationary post offices were fired or moved to other jobs because they were no longer needed to sort the mail. The clerks took great pride in their work and could sort up to 600 pieces of mail an hour, and up until the mid-1900s, railway mail service dominated the movement of the mail.

However, as airplanes and highways expanded and improved, the need for railway mail began to decline. Postal officials also began to move toward mechanical processing. On June 30, 1977, the very last railway mail car ended its final run when it pulled into Washington’s Union Station.

City: Washington, DC

Printing Method: Engraved

Perforations: 12

Color: Carmine

Railway Mail

On July 7, 1838, Congress approved an act that declared all United States railroads as post roads. This would lead to a dramatic increase in the use of railroads to deliver mail.

In the 1830s, businesses and individuals began to complain that mail delivery was too slow. At the time, it was carried by horse and stagecoach.

The postmaster general answered these calls by authorizing mail to be put on trains in the early 1830s. The first mail carried by train was delivered on December 5, 1832, aboard a train between Lancaster and West Chester, Pennsylvania.

The next major development came in May 1837, when John E. Kendall was made a route agent, marking the first time a clerk was appointed to accompany the mail on a railroad car. When the mail traveled on these trains, it usually sat unopened, waiting to be sorted at the local office.

To improve service, on July 7, 1838, Congress passed an act declaring all US railroads to be post roads. This act helped increase the use of railroads for mail delivery. It also led to a significant decrease in the use of post riders and horse-drawn vehicles. However, they were still used to deliver to post offices that weren’t along railway routes. In areas of the country that didn’t have railroads, contractors delivered the mail and were called star routes.

For nearly 30 years, trains were used to transport mail between post offices. The mailbags were loaded onto the trains and delivered to the post office where they were sorted. However, while some of the mail was delivered, many letters were returned to the bags and placed back on the trains to be sorted later. Several issues also arose. The post office and the railroads struggled to agree on a fixed rate for mail transported by rail. In some cases, this led to railroads refusing to deliver the mail. The post office felt the railroads were beyond their control and started to consider other options.

Soon the idea emerged to have mail clerks on the trains to sort the mail as it traveled between towns. In 1862, the idea was briefly tested on the Hannibal and St. Joseph line in Missouri. Then two years later, Chicago’s Assistant Postmaster George B. Armstrong pushed for the widespread use of a railway post office and succeeded. The first mail car, a renovated baggage car, ran on the Chicago and North Western Railroad line between Chicago and Clinton, Iowa, on August 28, 1864.

Clerks aboard the train sorted mail not just for routes along the line, but also for those beyond the end of the line. This new railway mail service proved a great success. More mail cars were added to travel between New York and Washington, New York, and Erie, Pennsylvania, as well as between Chicago and Burlington, Illinois, and Chicago and Rock Island, Illinois.

These trains didn’t always stop at every station, but those smaller stations still had mail. Early on, the trains had to slow down immensely so the clerks could grab the mailbags, which was both inefficient and dangerous. Eventually, they developed mail cranes. Mailbags were hung on a crane at stations that were too small for the train to stop. The clerk used a metal mar to grab the bag as the train passed at about 70 miles per hour.

By 1867, there were 18 railway mail routes that crossed over 4,435 miles of track with 160 clerks hard at work. They were so efficient that dozens of clerks at stationary post offices were fired or moved to other jobs because they were no longer needed to sort the mail. The clerks took great pride in their work and could sort up to 600 pieces of mail an hour, and up until the mid-1900s, railway mail service dominated the movement of the mail.

However, as airplanes and highways expanded and improved, the need for railway mail began to decline. Postal officials also began to move toward mechanical processing. On June 30, 1977, the very last railway mail car ended its final run when it pulled into Washington’s Union Station.