# H53 - 1893 1c Hawaii, purple, red overprint

Â

The Provisional Government

Queen Liliuokalani took the throne at a turbulent time in Hawaii’s history.  An economic depression was caused by the passage of the McKinley bill in the U.S.  This bill made the price of Hawaiian sugar uncompetitive with sugar grown in the U.S.  The sugar growers were very often prominent foreign businessmen, and they were often involved in the Hawaiian government for the specific purpose of protecting their own interests.  Most of these businessmen favored annexation to the U.S. for economic reasons.

When the queen attempted to put her own constitution into effect, some businessmen formed an annexation club.  This later became the Committee of Safety.  The changes to her constitution were considered revolutionary.  The most radical of these were: cabinet ministers were to serve “during the queen’s pleasure,†only male Hawaiian-born or naturalized subjects were allowed to vote, and nobles were appointed for life by the queen.  If this constitution had passed, the queen would have almost total control over the political affairs of the country, and the legislators’ powers would be severely limited.  Haoles, or white men, had become accustomed to running the Hawaiian government under the previous sovereigns.

The queen’s actions caused a panic among the businessmen in the community.  The Committee of Safety was formed, mainly made up of annexationists opposing the queen.  The Committee of Safety determined that the queen’s actions were a detriment to society, and called upon the United States for assistance in securing the public well-being. Â

Members of the committee obtained U.S. authority to set up a provisional government, and they wasted no time in doing so.  A U.S. ship called the Boston was in Honolulu’s harbor at the time.  Troops from the Boston took possession of the government office building, the Aliiolani Hale, on January 17, 1892.  The provisional government was in place the next day.

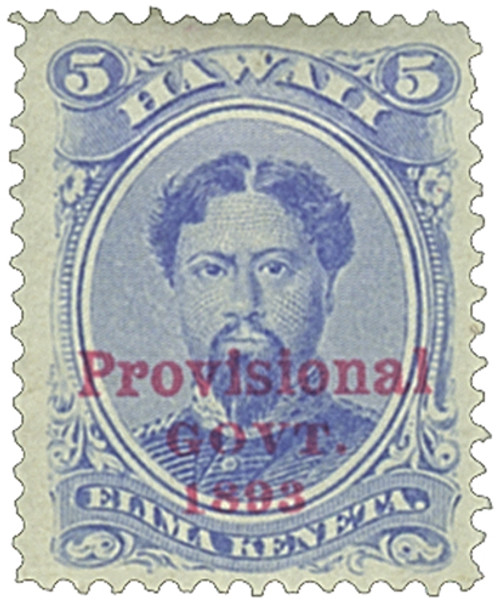

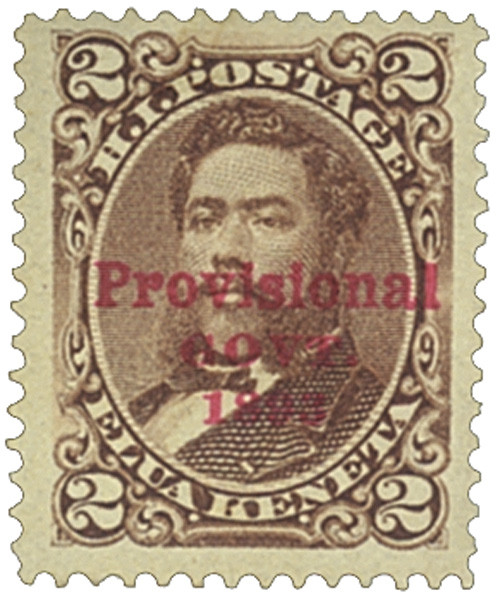

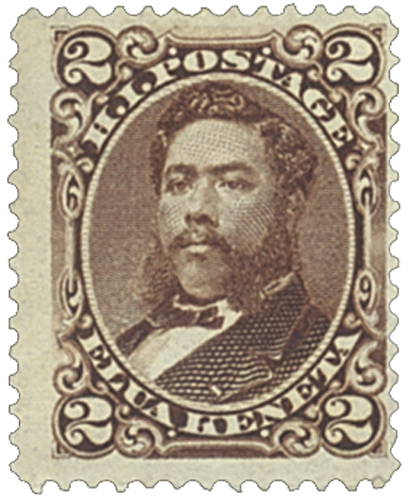

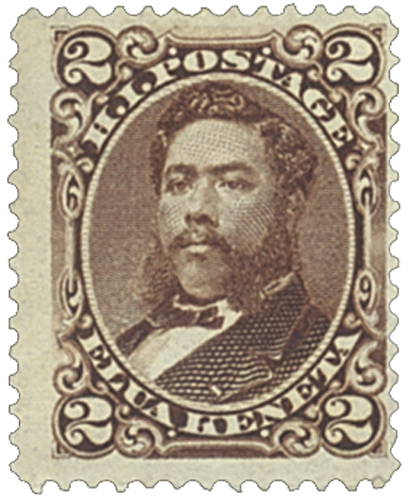

On May 20, 1893, the stamps of the Kingdom of Hawaii went on sale with the overprint of “Provisional GOVT. 1893.† The newly appointed Postmaster General was Joseph M. Oat.  Oat’s predecessor, Walter Hill, was ousted from his position.  Overprinting of the stamps was done with great haste by the Hawaiian Gazette Co.  There was a strong demand for the overprinted stamps, and the 2¢ bright vermillion sold out on the first day it was placed on sale.

The U.S. Annexes HawaiiÂ

On July 7, 1898, President William McKinley signed legislation annexing Hawaii, paving the way for it to become a U.S. state.

Polynesians were the first people to settle the Hawaiian Islands. They journeyed across the Pacific, moving from island to island in giant canoes, and likely reached Hawaii around 2,000 years ago. Another group from Tahiti reached the islands in 1200 A.D. and conquered the earlier settlers. The name Hawaii is either derived from the name of a hero from a Hawaiian legend, Hawai’iloa, or the name of the Polynesian homeland to the west, Hawaiki.

Although European or Japanese ships may have reached the Hawaiian Islands during the 1500s, Great Britain’s Captain James Cook was responsible for making them known to the rest of the world. Cook landed there on January 18, 1778, and engaged in friendly trade. It’s estimated that about 300,000 people lived in Hawaii at that time. The Hawaiians believed Cook had divine powers and considered him a great chief. He named the islands in honor of the first lord of the British admiralty, the Earl of Sandwich, and left after two weeks. He returned in November 1778, and was later killed when a fight broke out between the Hawaiians and his men.

Cook’s voyages brought more explorers and traders to Hawaii. The first trading ship stopped there in 1786 while transporting a load of furs from Oregon to China. New types of livestock, manufactured goods, and plants were introduced to the islands. Unfortunately, new diseases took a devastating toll on the islanders.

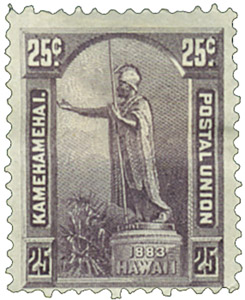

Local chiefs had controlled the islands throughout Hawaii’s history. In 1782, Chief Kamehameha obtained firearms from European traders and began a bloody war to unite the islands into a kingdom. By 1792, he controlled Hawaii Island. Three years later, he controlled all the main islands except Kauai and Niihau. Kamehameha appointed the local chiefs as governors and proclaimed himself King Kamehameha I. The chiefs of Kauai and Niihau accepted Kamehameha’s rule in 1810.

From 1811 to 1830, Hawaii shipped large supplies of sandalwood to China. Money from this lucrative trade allowed the Hawaiians to purchase weapons, ships, and other supplies. From then until the 1860s, Hawaii’s greatest source of income was the sale of fresh water and other supplies to whaling ships. The first permanent sugar cane plantation in Hawaii was started at Koloa on Kauai Island in 1835. In 1885, the first pineapples were brought to the islands from Jamaica. The British horticulturist Captain John Kidwell imported the plants. Even today, sugar cane and pineapples remain Hawaii’s most profitable crops.

Kamehameha’s son, crowned Kamehameha II in 1819, banned the official religion of the Hawaiian Kingdom and disbanded its orders of priests. In 1820, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent Protestant missionaries and teachers to the islands. Most Hawaiians converted to Christianity. In 1827, Roman Catholic missionaries arrived. These missionaries met resistance from the chiefs who considered Protestantism the official religion. The Roman Catholics were forced to leave in 1831. Efforts were made to prevent new Catholics from arriving, and many Hawaiians practicing Catholicism were jailed. In July 1839, French Captain C.P.T. Laplace of the frigate L’Artémise blockaded Honolulu. Laplace demanded Roman Catholics have religious freedom and threatened to destroy Honolulu. As a result, the Hawaiians granted the Catholics their freedom.

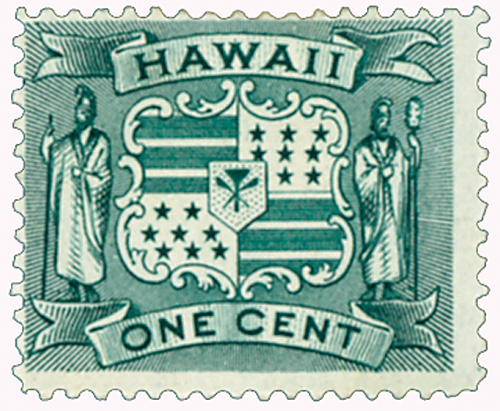

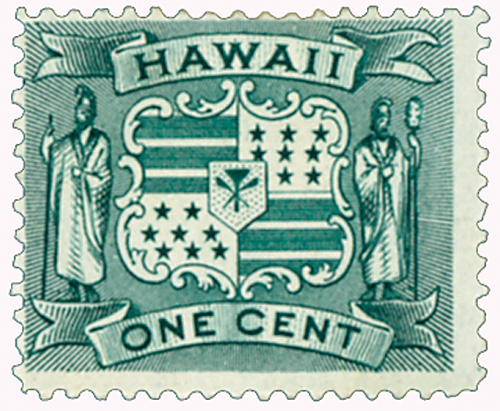

Hawaii adopted its first constitution in 1840, which provided for an executive, a legislature, and a supreme court. The legislature consisted of a house of chiefs and a house of elected representatives. The United States recognized Hawaii as an independent government in 1842.

Before 1848, the king owned all the land in Hawaii. That year, land reforms were enacted under the Great MÄhele. Land was distributed to chiefs who divided it into homesteads. Some land was sold to foreigners. From 1854 to 1900, Hawaii’s economic opportunities attracted a great number of foreigners. Chinese, Polynesians, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipinos, Koreans, and Puerto Ricans all came to the islands.

King KÄlakaua gave the U.S. the right to use Pearl Harbor as a naval base in 1887 in return for trading privileges. In 1891, KÄlakaua died and his sister was crowned Queen Liliuokalani. Liliuokalani attempted to install a new constitution that would increase her power. In 1893, a group of nine Americans, two Britons, and two Germans led a revolution against Liliuokalani, removing her from office. U.S. marines and sailors aided the revolutionaries. In 1894, the Republic of Hawaii was formed. This short-lived nation had just one president, Sanford B. Dole.

Soon, Hawaii was controlled by U.S. businessmen who began to lobby for its annexation by America. Following the explosion of the battleship Maine in Havana harbor and the ensuing Spanish-American War, some members of Congress began to realize the strategic importance of Hawaii as a mid-Pacific fueling station and naval base. These Congressmen then submitted a proposal to annex Hawaii. The joint resolution passed and was signed into law by President William McKinley on July 7, 1898. McKinley had long supported the idea, claiming, “We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny.â€

Hawaii later became a U.S. territory on June 14, 1900, and Hawaiians became U.S. citizens. However, their congressional representative could not vote and the U.S. Congress could veto any law passed by their legislature. The first bill attempting to make Hawaii a state was introduced in 1919. In 1950, Hawaii adopted a constitution in preparation for statehood. Congress approved the appropriate legislation in 1959 and President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill. The matter went before the Hawaiian people, who voted 17 to 1 in favor of statehood. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became a U.S. state.

Â

Â

The Provisional Government

Queen Liliuokalani took the throne at a turbulent time in Hawaii’s history.  An economic depression was caused by the passage of the McKinley bill in the U.S.  This bill made the price of Hawaiian sugar uncompetitive with sugar grown in the U.S.  The sugar growers were very often prominent foreign businessmen, and they were often involved in the Hawaiian government for the specific purpose of protecting their own interests.  Most of these businessmen favored annexation to the U.S. for economic reasons.

When the queen attempted to put her own constitution into effect, some businessmen formed an annexation club.  This later became the Committee of Safety.  The changes to her constitution were considered revolutionary.  The most radical of these were: cabinet ministers were to serve “during the queen’s pleasure,†only male Hawaiian-born or naturalized subjects were allowed to vote, and nobles were appointed for life by the queen.  If this constitution had passed, the queen would have almost total control over the political affairs of the country, and the legislators’ powers would be severely limited.  Haoles, or white men, had become accustomed to running the Hawaiian government under the previous sovereigns.

The queen’s actions caused a panic among the businessmen in the community.  The Committee of Safety was formed, mainly made up of annexationists opposing the queen.  The Committee of Safety determined that the queen’s actions were a detriment to society, and called upon the United States for assistance in securing the public well-being. Â

Members of the committee obtained U.S. authority to set up a provisional government, and they wasted no time in doing so.  A U.S. ship called the Boston was in Honolulu’s harbor at the time.  Troops from the Boston took possession of the government office building, the Aliiolani Hale, on January 17, 1892.  The provisional government was in place the next day.

On May 20, 1893, the stamps of the Kingdom of Hawaii went on sale with the overprint of “Provisional GOVT. 1893.† The newly appointed Postmaster General was Joseph M. Oat.  Oat’s predecessor, Walter Hill, was ousted from his position.  Overprinting of the stamps was done with great haste by the Hawaiian Gazette Co.  There was a strong demand for the overprinted stamps, and the 2¢ bright vermillion sold out on the first day it was placed on sale.

The U.S. Annexes HawaiiÂ

On July 7, 1898, President William McKinley signed legislation annexing Hawaii, paving the way for it to become a U.S. state.

Polynesians were the first people to settle the Hawaiian Islands. They journeyed across the Pacific, moving from island to island in giant canoes, and likely reached Hawaii around 2,000 years ago. Another group from Tahiti reached the islands in 1200 A.D. and conquered the earlier settlers. The name Hawaii is either derived from the name of a hero from a Hawaiian legend, Hawai’iloa, or the name of the Polynesian homeland to the west, Hawaiki.

Although European or Japanese ships may have reached the Hawaiian Islands during the 1500s, Great Britain’s Captain James Cook was responsible for making them known to the rest of the world. Cook landed there on January 18, 1778, and engaged in friendly trade. It’s estimated that about 300,000 people lived in Hawaii at that time. The Hawaiians believed Cook had divine powers and considered him a great chief. He named the islands in honor of the first lord of the British admiralty, the Earl of Sandwich, and left after two weeks. He returned in November 1778, and was later killed when a fight broke out between the Hawaiians and his men.

Cook’s voyages brought more explorers and traders to Hawaii. The first trading ship stopped there in 1786 while transporting a load of furs from Oregon to China. New types of livestock, manufactured goods, and plants were introduced to the islands. Unfortunately, new diseases took a devastating toll on the islanders.

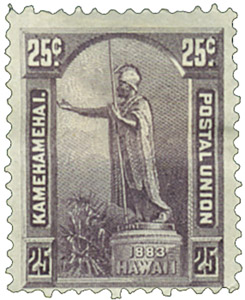

Local chiefs had controlled the islands throughout Hawaii’s history. In 1782, Chief Kamehameha obtained firearms from European traders and began a bloody war to unite the islands into a kingdom. By 1792, he controlled Hawaii Island. Three years later, he controlled all the main islands except Kauai and Niihau. Kamehameha appointed the local chiefs as governors and proclaimed himself King Kamehameha I. The chiefs of Kauai and Niihau accepted Kamehameha’s rule in 1810.

From 1811 to 1830, Hawaii shipped large supplies of sandalwood to China. Money from this lucrative trade allowed the Hawaiians to purchase weapons, ships, and other supplies. From then until the 1860s, Hawaii’s greatest source of income was the sale of fresh water and other supplies to whaling ships. The first permanent sugar cane plantation in Hawaii was started at Koloa on Kauai Island in 1835. In 1885, the first pineapples were brought to the islands from Jamaica. The British horticulturist Captain John Kidwell imported the plants. Even today, sugar cane and pineapples remain Hawaii’s most profitable crops.

Kamehameha’s son, crowned Kamehameha II in 1819, banned the official religion of the Hawaiian Kingdom and disbanded its orders of priests. In 1820, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent Protestant missionaries and teachers to the islands. Most Hawaiians converted to Christianity. In 1827, Roman Catholic missionaries arrived. These missionaries met resistance from the chiefs who considered Protestantism the official religion. The Roman Catholics were forced to leave in 1831. Efforts were made to prevent new Catholics from arriving, and many Hawaiians practicing Catholicism were jailed. In July 1839, French Captain C.P.T. Laplace of the frigate L’Artémise blockaded Honolulu. Laplace demanded Roman Catholics have religious freedom and threatened to destroy Honolulu. As a result, the Hawaiians granted the Catholics their freedom.

Hawaii adopted its first constitution in 1840, which provided for an executive, a legislature, and a supreme court. The legislature consisted of a house of chiefs and a house of elected representatives. The United States recognized Hawaii as an independent government in 1842.

Before 1848, the king owned all the land in Hawaii. That year, land reforms were enacted under the Great MÄhele. Land was distributed to chiefs who divided it into homesteads. Some land was sold to foreigners. From 1854 to 1900, Hawaii’s economic opportunities attracted a great number of foreigners. Chinese, Polynesians, Japanese, Portuguese, Filipinos, Koreans, and Puerto Ricans all came to the islands.

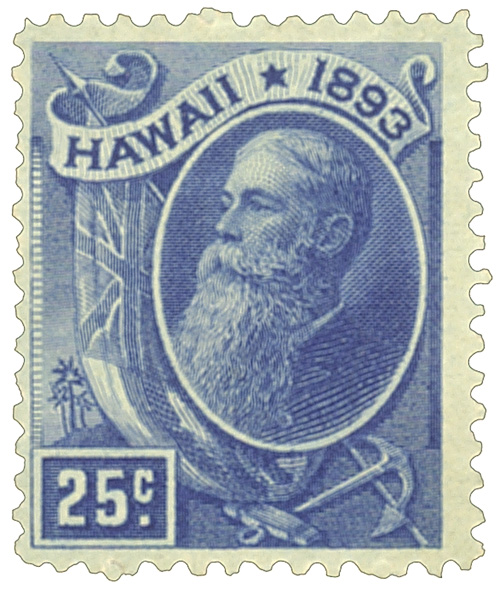

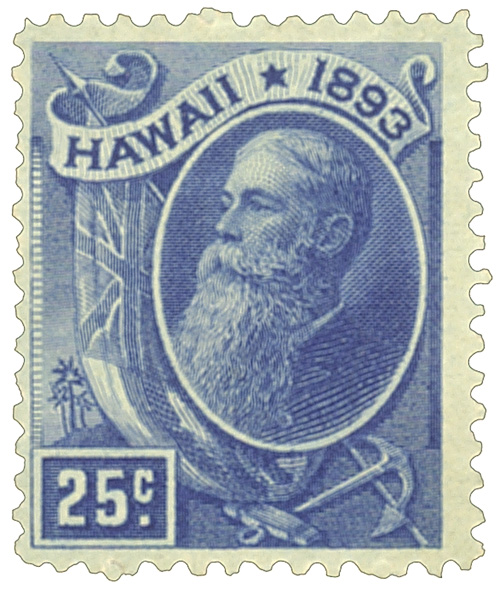

King KÄlakaua gave the U.S. the right to use Pearl Harbor as a naval base in 1887 in return for trading privileges. In 1891, KÄlakaua died and his sister was crowned Queen Liliuokalani. Liliuokalani attempted to install a new constitution that would increase her power. In 1893, a group of nine Americans, two Britons, and two Germans led a revolution against Liliuokalani, removing her from office. U.S. marines and sailors aided the revolutionaries. In 1894, the Republic of Hawaii was formed. This short-lived nation had just one president, Sanford B. Dole.

Soon, Hawaii was controlled by U.S. businessmen who began to lobby for its annexation by America. Following the explosion of the battleship Maine in Havana harbor and the ensuing Spanish-American War, some members of Congress began to realize the strategic importance of Hawaii as a mid-Pacific fueling station and naval base. These Congressmen then submitted a proposal to annex Hawaii. The joint resolution passed and was signed into law by President William McKinley on July 7, 1898. McKinley had long supported the idea, claiming, “We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny.â€

Hawaii later became a U.S. territory on June 14, 1900, and Hawaiians became U.S. citizens. However, their congressional representative could not vote and the U.S. Congress could veto any law passed by their legislature. The first bill attempting to make Hawaii a state was introduced in 1919. In 1950, Hawaii adopted a constitution in preparation for statehood. Congress approved the appropriate legislation in 1959 and President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the bill. The matter went before the Hawaiian people, who voted 17 to 1 in favor of statehood. On August 21, 1959, Hawaii became a U.S. state.

Â