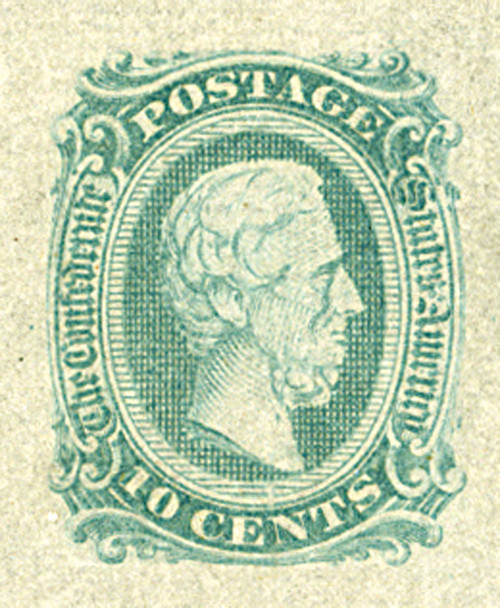

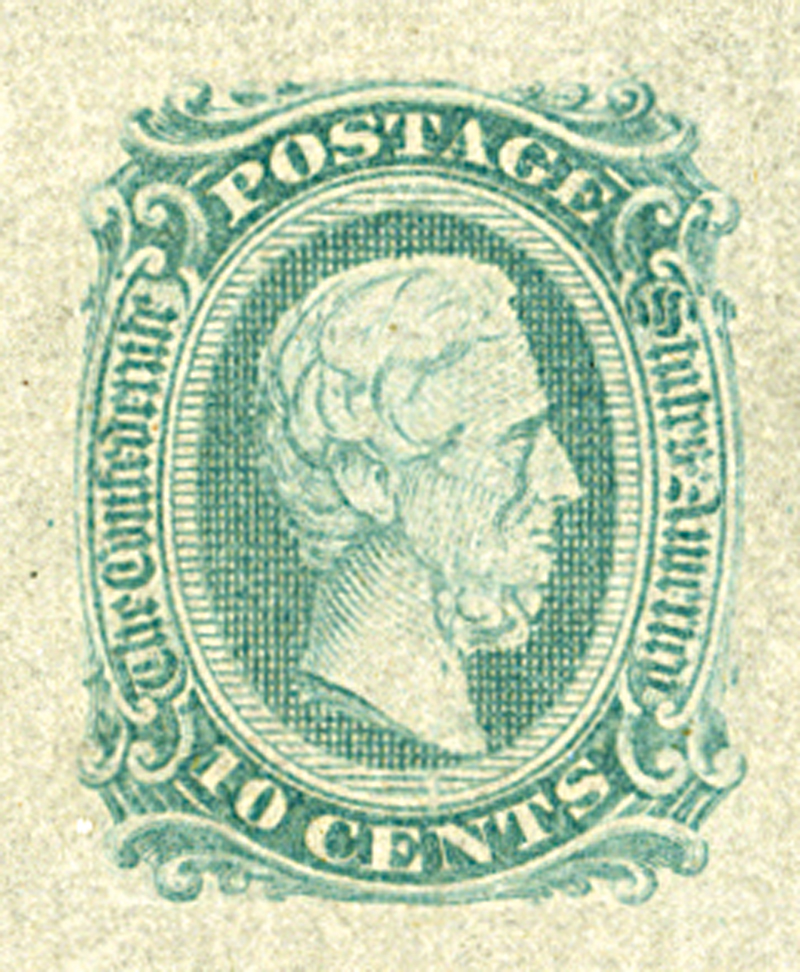

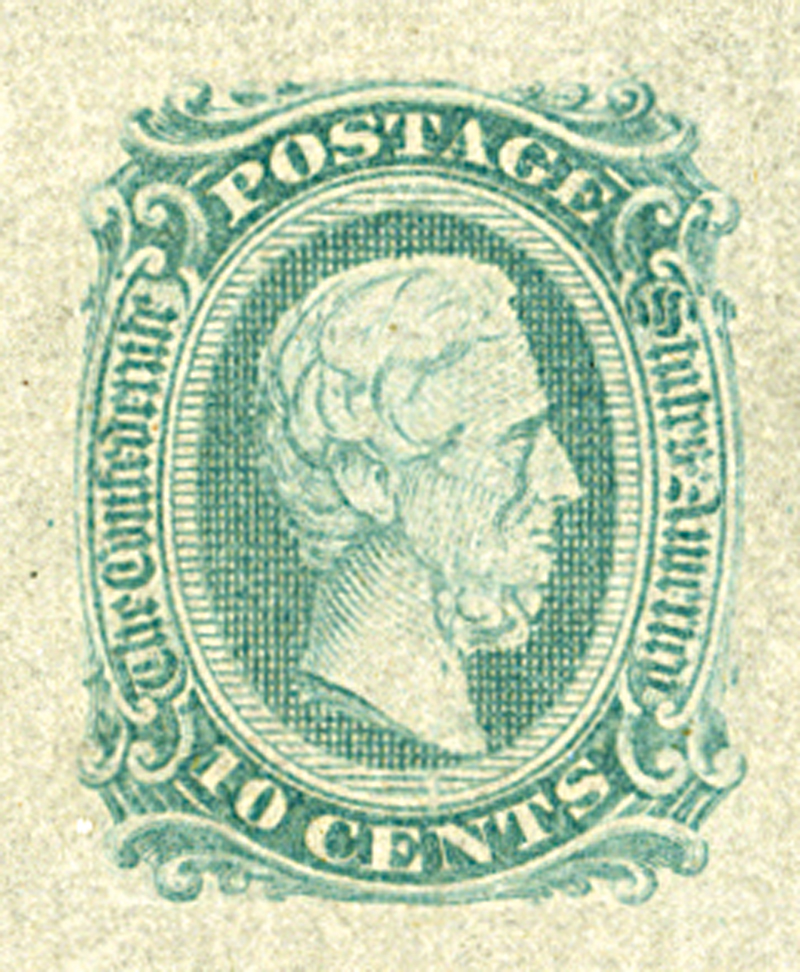

# CSA11c - 1863-64 10c Confederate States - Jefferson Davis - greenish-blue, no frame-line (Die A)

Lincoln Suspends Writ of Habeas Corpus

On April 27, 1861, Abraham Lincoln became the first US president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus – the right to be released from unlawful detention. He took this controversial move in the hopes it would prevent Maryland from joining the Confederacy.

When the Civil War began in April 1861, Congress could not convene until July, meaning that President Lincoln had to make his war-time decisions without the advice or consent of Congress. He called upon his presidential war powers to create a blockade on the South and distribute funds without Congressional permission.

Slave states that didn’t declare their secession from the Union became hotly contested as the nation spiraled into Civil War. Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and a portion of Virginia that became West Virginia all remained in the Union while generally opposing military action against the new Confederacy. Loyalties were often mixed, even within families. Many of these “border states†also had social, political, and economic ties to both the North and South. More of their trade was with the North, but as slave states, many of their residents were sympathetic to the Confederate cause.

Maryland was especially important to the Federal government in April 1861. Maryland falling into Confederate hands would have meant Washington, DC, would be surrounded. Vital rail and telegraph lines passed from the west and north through Baltimore on their way to Washington. Additionally, troops summoned to defend the capital also needed to travel through Baltimore. At the time, there was no direct connection between Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad’s tracks and those of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, so railcars transferring between the two had to be pulled by horse along Pratt Street for over a mile. On April 19, 1861, a crowd of anti-war “Copperheads†and other Southern sympathizers attempted to prevent the 6th Massachusetts Militia from transferring between the two lines, in an event that became known as the Baltimore Riot of 1861. The mob prevented the cars from being pulled by horse, forcing the soldiers to march the remaining distance on foot. As they marched, the rear companies were attacked with cobblestones and bricks. Some of the soldiers shot into the crowds before the Baltimore police gained control of the situation separating the two groups. Four soldiers and twelve civilians were killed.

Following the riot, the Maryland legislature met. They voted against secession, but voted to close the railways to Union troops. Lincoln was so determined to keep passage through Maryland open for Union troops that he resorted to extreme measures. In a shocking turn of events, on April 27, Lincoln suspended the Constitutional privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus (Latin for “show me the bodyâ€) along the military lines from Washington, DC, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Habeas corpus is the personal right that an arrested person must be charged with a specific crime, or they must be released. It serves as a safeguard against unlawful seizures. In taking this action, Lincoln was authorizing the US Army to arrest and hold anyone they wanted. Though it was a controversial move, Lincoln viewed it as necessary to protect DC and end further talks of secession.

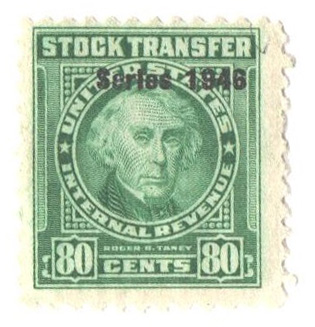

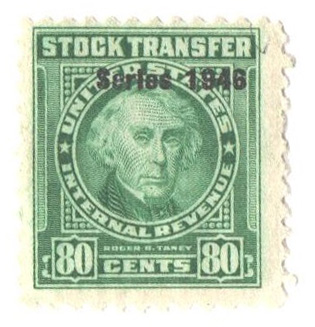

A month later, US soldiers arrested John Merryman, a lieutenant in the Maryland state militia. He had been ordered by the governor to burn rail bridges, preventing Northern troops from entering the city of Baltimore. Merryman was imprisoned at Fort McHenry without charges or legal counsel. Upon hearing of the situation, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney issued a Writ of Habeas Corpus, but it was refused at the fort’s gate. Taney submitted his written opinion on the situation to the president, claiming he had overstepped his Constitutional limits. President Lincoln responded that without Congress in session, he had to act on their behalf.

Taney urged other judges to follow his lead and issue writs to the growing number of border states secessionists who were being detained. Frustrated, Lincoln issued a presidential arrest warrant for the sitting chief justice of the Supreme Court. When Congress finally convened in July 1861, it failed to pass a resolution supporting Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus. Lincoln released most of the prisoners in February 1862, bringing an end to the court challenges. He again suspended habeas corpus that September when people opposed his calling up of the militia. Later that year, Congress passed the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which Lincoln signed into law on March 3, 1863. It remained in effect until Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, repealed it on December 1, 1865.

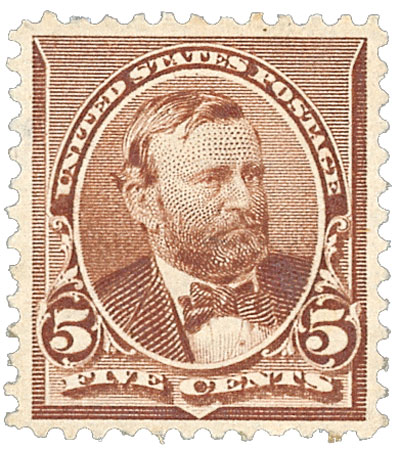

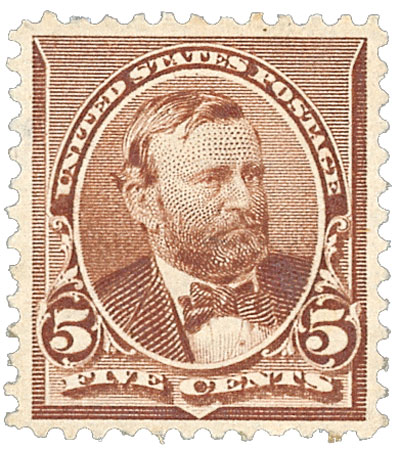

In the years since the Civil War, other presidents have suspended the writ in times of crisis. Ulysses S. Grant suspended habeas corpus under the Civil Rights Act of 1871 in response to the Ku Klux Klan’s opposition of Reconstruction. Franklin Roosevelt suspended habeas corpus during World War II and George W. Bush called upon the power to after the September 11 attacks, but this move was overturned.

Â

Lincoln Suspends Writ of Habeas Corpus

On April 27, 1861, Abraham Lincoln became the first US president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus – the right to be released from unlawful detention. He took this controversial move in the hopes it would prevent Maryland from joining the Confederacy.

When the Civil War began in April 1861, Congress could not convene until July, meaning that President Lincoln had to make his war-time decisions without the advice or consent of Congress. He called upon his presidential war powers to create a blockade on the South and distribute funds without Congressional permission.

Slave states that didn’t declare their secession from the Union became hotly contested as the nation spiraled into Civil War. Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and a portion of Virginia that became West Virginia all remained in the Union while generally opposing military action against the new Confederacy. Loyalties were often mixed, even within families. Many of these “border states†also had social, political, and economic ties to both the North and South. More of their trade was with the North, but as slave states, many of their residents were sympathetic to the Confederate cause.

Maryland was especially important to the Federal government in April 1861. Maryland falling into Confederate hands would have meant Washington, DC, would be surrounded. Vital rail and telegraph lines passed from the west and north through Baltimore on their way to Washington. Additionally, troops summoned to defend the capital also needed to travel through Baltimore. At the time, there was no direct connection between Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad’s tracks and those of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, so railcars transferring between the two had to be pulled by horse along Pratt Street for over a mile. On April 19, 1861, a crowd of anti-war “Copperheads†and other Southern sympathizers attempted to prevent the 6th Massachusetts Militia from transferring between the two lines, in an event that became known as the Baltimore Riot of 1861. The mob prevented the cars from being pulled by horse, forcing the soldiers to march the remaining distance on foot. As they marched, the rear companies were attacked with cobblestones and bricks. Some of the soldiers shot into the crowds before the Baltimore police gained control of the situation separating the two groups. Four soldiers and twelve civilians were killed.

Following the riot, the Maryland legislature met. They voted against secession, but voted to close the railways to Union troops. Lincoln was so determined to keep passage through Maryland open for Union troops that he resorted to extreme measures. In a shocking turn of events, on April 27, Lincoln suspended the Constitutional privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus (Latin for “show me the bodyâ€) along the military lines from Washington, DC, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Habeas corpus is the personal right that an arrested person must be charged with a specific crime, or they must be released. It serves as a safeguard against unlawful seizures. In taking this action, Lincoln was authorizing the US Army to arrest and hold anyone they wanted. Though it was a controversial move, Lincoln viewed it as necessary to protect DC and end further talks of secession.

A month later, US soldiers arrested John Merryman, a lieutenant in the Maryland state militia. He had been ordered by the governor to burn rail bridges, preventing Northern troops from entering the city of Baltimore. Merryman was imprisoned at Fort McHenry without charges or legal counsel. Upon hearing of the situation, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney issued a Writ of Habeas Corpus, but it was refused at the fort’s gate. Taney submitted his written opinion on the situation to the president, claiming he had overstepped his Constitutional limits. President Lincoln responded that without Congress in session, he had to act on their behalf.

Taney urged other judges to follow his lead and issue writs to the growing number of border states secessionists who were being detained. Frustrated, Lincoln issued a presidential arrest warrant for the sitting chief justice of the Supreme Court. When Congress finally convened in July 1861, it failed to pass a resolution supporting Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus. Lincoln released most of the prisoners in February 1862, bringing an end to the court challenges. He again suspended habeas corpus that September when people opposed his calling up of the militia. Later that year, Congress passed the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which Lincoln signed into law on March 3, 1863. It remained in effect until Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, repealed it on December 1, 1865.

In the years since the Civil War, other presidents have suspended the writ in times of crisis. Ulysses S. Grant suspended habeas corpus under the Civil Rights Act of 1871 in response to the Ku Klux Klan’s opposition of Reconstruction. Franklin Roosevelt suspended habeas corpus during World War II and George W. Bush called upon the power to after the September 11 attacks, but this move was overturned.

Â