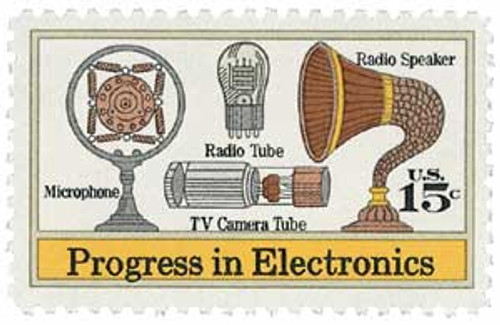

# AC506 FDC - 7/10/1973, USA, Postcard, Progress in Electronics Series of 1973

First Day Cover Honors Marconi's Electronics Progress

Issued to commemorate the progress made in electronics, the stamp on this First Day Cover (#1500) features Guglielmo Marconi's spark coil and spark gap, which enabled him to transmit across the Atlantic Ocean by wireless radio. The cachet pictures Marconi and his invention.

First Successful Wireless Communication Over Water

On May 13, 1897, Guglielmo Marconi sent the world’s first wireless communication over open sea.

Born in Bologna, Italy, on April 25, 1874, Guglielmo Marconi spent his early years in his native country as well as Bedford, England. He reportedly didn’t do well in school, but had an interest in science and electricity.

By the early 1890s, he became invested in the idea of “wireless telegraphy” (sending telegraph messages without the use of wires). He wasn’t the first person to explore this – in fact, people had been exploring the idea for over 50 years – but none were successful. Though Heinrich Hertz introduced the idea of electromagnetic radiation (radio waves) in 1888. At the time, most scientists believed that radio was like an invisible form of light that could only be detected within a line of sight.

Marconi believed radio waves were the key to wireless communication and dedicated himself to it. Just 20 years old, he began building his own equipment in his attic, aided by his butler. Among his early inventions was a storm alarm in 1894 that rang a bell when there was lighting. Later, he was able to make a bell on the other side of the room ring by pushing a telegraphic button. When he showed his experiments to his parents, his father gave him all the money he had on him at the time to buy more materials.

Marconi furthered his inventions by studying the research of physicists who experimented with radio waves. While to many radio waves were little more than a laboratory experiment, Marconi used them to create a new communication system. In a short time he developed portable transmitters and receiver systems that could work over long distance.

By 1895, Marconi was ready to take his experiment outside. Trying a variety of arrangements and antenna shapes, he was unable to send signals over half a mile away, which had previously been predicted as the maximum distance for radio wave transmission. But he soon made a breakthrough. Marconi discovered that his transmissions could go farther if he raised his antenna higher and grounded the transmitter and receiver. Soon he could send transmissions up to two miles away and over hills. He realized the commercial and military value of his invention and asked for funding from the Ministry of Post and telegraphs. The minister never responded and Marconi was convinced to go to England, where he would have better luck getting funding.

Once in England, Marconi arranged for his first demonstration with the British government in July 1896. After that success he held several more, eventually transmitting signals up to 3.7 miles over land. He then hit a major milestone on May 13, 1897. Marconi successfully sent the first-ever wireless transmission over open sea. From his location in Flat Holm Island, he sent the message “Are you ready?” 3.7 miles over the Bristol Channel to Lavernock Point.

The British were extremely impressed with Marconi’s success and introduced his findings to the public over a series of lectures. He soon received international attention. In the next couple years he triumphantly returned to Italy for a demonstration, successfully transmitted messages across the English Channel, and made his first presentation in America.

Though many doubted it was possible, Marconi was convinced that he could send a message across the Atlantic Ocean. He achieved that victory on December 12, 1901, sending a message 2,200 miles from England to Canada. For his pioneering work, Marconi later received the Nobel Prize in Physics.

First Day Cover Honors Marconi's Electronics Progress

Issued to commemorate the progress made in electronics, the stamp on this First Day Cover (#1500) features Guglielmo Marconi's spark coil and spark gap, which enabled him to transmit across the Atlantic Ocean by wireless radio. The cachet pictures Marconi and his invention.

First Successful Wireless Communication Over Water

On May 13, 1897, Guglielmo Marconi sent the world’s first wireless communication over open sea.

Born in Bologna, Italy, on April 25, 1874, Guglielmo Marconi spent his early years in his native country as well as Bedford, England. He reportedly didn’t do well in school, but had an interest in science and electricity.

By the early 1890s, he became invested in the idea of “wireless telegraphy” (sending telegraph messages without the use of wires). He wasn’t the first person to explore this – in fact, people had been exploring the idea for over 50 years – but none were successful. Though Heinrich Hertz introduced the idea of electromagnetic radiation (radio waves) in 1888. At the time, most scientists believed that radio was like an invisible form of light that could only be detected within a line of sight.

Marconi believed radio waves were the key to wireless communication and dedicated himself to it. Just 20 years old, he began building his own equipment in his attic, aided by his butler. Among his early inventions was a storm alarm in 1894 that rang a bell when there was lighting. Later, he was able to make a bell on the other side of the room ring by pushing a telegraphic button. When he showed his experiments to his parents, his father gave him all the money he had on him at the time to buy more materials.

Marconi furthered his inventions by studying the research of physicists who experimented with radio waves. While to many radio waves were little more than a laboratory experiment, Marconi used them to create a new communication system. In a short time he developed portable transmitters and receiver systems that could work over long distance.

By 1895, Marconi was ready to take his experiment outside. Trying a variety of arrangements and antenna shapes, he was unable to send signals over half a mile away, which had previously been predicted as the maximum distance for radio wave transmission. But he soon made a breakthrough. Marconi discovered that his transmissions could go farther if he raised his antenna higher and grounded the transmitter and receiver. Soon he could send transmissions up to two miles away and over hills. He realized the commercial and military value of his invention and asked for funding from the Ministry of Post and telegraphs. The minister never responded and Marconi was convinced to go to England, where he would have better luck getting funding.

Once in England, Marconi arranged for his first demonstration with the British government in July 1896. After that success he held several more, eventually transmitting signals up to 3.7 miles over land. He then hit a major milestone on May 13, 1897. Marconi successfully sent the first-ever wireless transmission over open sea. From his location in Flat Holm Island, he sent the message “Are you ready?” 3.7 miles over the Bristol Channel to Lavernock Point.

The British were extremely impressed with Marconi’s success and introduced his findings to the public over a series of lectures. He soon received international attention. In the next couple years he triumphantly returned to Italy for a demonstration, successfully transmitted messages across the English Channel, and made his first presentation in America.

Though many doubted it was possible, Marconi was convinced that he could send a message across the Atlantic Ocean. He achieved that victory on December 12, 1901, sending a message 2,200 miles from England to Canada. For his pioneering work, Marconi later received the Nobel Prize in Physics.