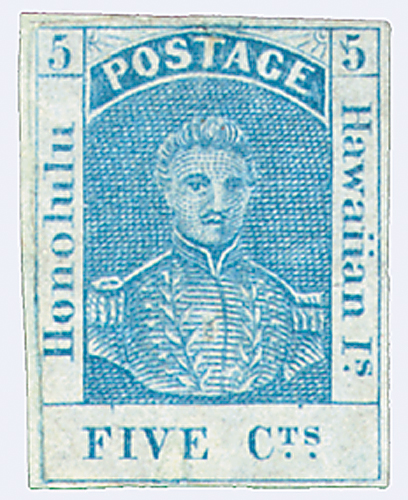

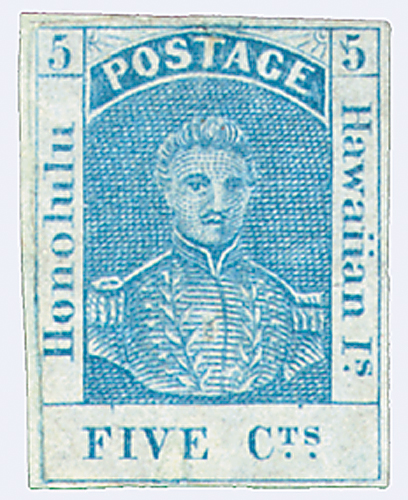

# H9 - 1861 5c Hawaii, blue, thin bluish wove paper

Why some Hawaii stamps were

created just for stamp collectors...

There was a great demand for Hawaii stamps from collectors in the United States. Hawaii’s connection to the U.S. was quite strong, and it was evident to many people that Hawaii would eventually become a U.S. state. This made the stamps popular in the U.S. But the small number of Hawaii stamps issued for postal purposes could not possibly supply demand. Postal authorities created “official imitations” and reproductions, thereby collecting a sizable profit on stamps that would never frank mail.

Hawaiian Independence Day

On November 28, 1843, France and the United Kingdom officially recognized Hawaii as an independent Kingdom.

After the death of King Kamehameha in 1819, his wife, newly converted Protestant Queen regent Ka’ahumanu, outlawed Catholicism in Hawaii. French Catholic priests were deported and native Hawaiian Catholic converts were arrested. They were later freed when they rejected Catholicism.

Then in 1839, the French government sent captain Cyrille Pierre Théodore Laplace to Hawaii. Laplace was ordered to threaten King Kamehameha III with war if he didn’t issue the Edict of Toleration. This decree called for the creation of the Hawaiian Catholic Church and the king also had to pay $20,000 in compensation to the French government. The Catholic missionaries were then allowed to return to Hawaii and were given land to build a church.

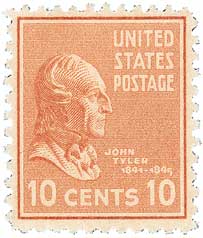

This incident, known as the Laplace Affair, made King Kamehameha III worry about future foreign intrusions. He decided to send diplomats to the U.S. and Europe to get official recognition of Hawaii’s independence. The diplomats left in mid-1842 and by December of that year, U.S. President John Tyler assured them that the U.S. would recognize their independence.

It took a bit longer for the British and French to recognize their independence. The first meeting with the British was unsuccessful, but after the delegation traveled to Belgium, that nations king promised to use his influence to help their cause. In March and April 1843, French and British representatives said their respective leaders would acknowledge Hawaii’s independence. However, during this time a British naval captain landed in Hawaii and occupied it for five months in the name of Queen Victoria. On July 31, 1843, King Kamehameha III was restored to power.

On November 28, 1843, British, and French representatives met at the Court of London to sign the Anglo-French Proclamation, formally recognizing Hawaii’s independence. Despite President Tyler’s earlier assurance, the U.S. didn’t sign the proclamation because it needed to be ratified by the U.S. Senate. However, in 1846 Tyler’s Secretary of State John C. Calhoun sent Hawaii a formal recognition of its independence.

Why some Hawaii stamps were

created just for stamp collectors...

There was a great demand for Hawaii stamps from collectors in the United States. Hawaii’s connection to the U.S. was quite strong, and it was evident to many people that Hawaii would eventually become a U.S. state. This made the stamps popular in the U.S. But the small number of Hawaii stamps issued for postal purposes could not possibly supply demand. Postal authorities created “official imitations” and reproductions, thereby collecting a sizable profit on stamps that would never frank mail.

Hawaiian Independence Day

On November 28, 1843, France and the United Kingdom officially recognized Hawaii as an independent Kingdom.

After the death of King Kamehameha in 1819, his wife, newly converted Protestant Queen regent Ka’ahumanu, outlawed Catholicism in Hawaii. French Catholic priests were deported and native Hawaiian Catholic converts were arrested. They were later freed when they rejected Catholicism.

Then in 1839, the French government sent captain Cyrille Pierre Théodore Laplace to Hawaii. Laplace was ordered to threaten King Kamehameha III with war if he didn’t issue the Edict of Toleration. This decree called for the creation of the Hawaiian Catholic Church and the king also had to pay $20,000 in compensation to the French government. The Catholic missionaries were then allowed to return to Hawaii and were given land to build a church.

This incident, known as the Laplace Affair, made King Kamehameha III worry about future foreign intrusions. He decided to send diplomats to the U.S. and Europe to get official recognition of Hawaii’s independence. The diplomats left in mid-1842 and by December of that year, U.S. President John Tyler assured them that the U.S. would recognize their independence.

It took a bit longer for the British and French to recognize their independence. The first meeting with the British was unsuccessful, but after the delegation traveled to Belgium, that nations king promised to use his influence to help their cause. In March and April 1843, French and British representatives said their respective leaders would acknowledge Hawaii’s independence. However, during this time a British naval captain landed in Hawaii and occupied it for five months in the name of Queen Victoria. On July 31, 1843, King Kamehameha III was restored to power.

On November 28, 1843, British, and French representatives met at the Court of London to sign the Anglo-French Proclamation, formally recognizing Hawaii’s independence. Despite President Tyler’s earlier assurance, the U.S. didn’t sign the proclamation because it needed to be ratified by the U.S. Senate. However, in 1846 Tyler’s Secretary of State John C. Calhoun sent Hawaii a formal recognition of its independence.