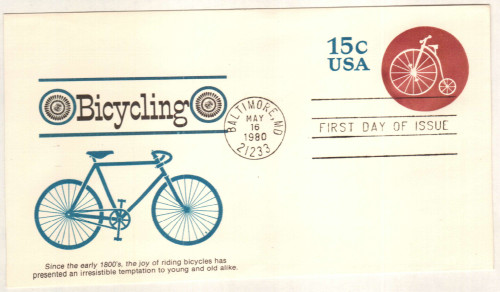

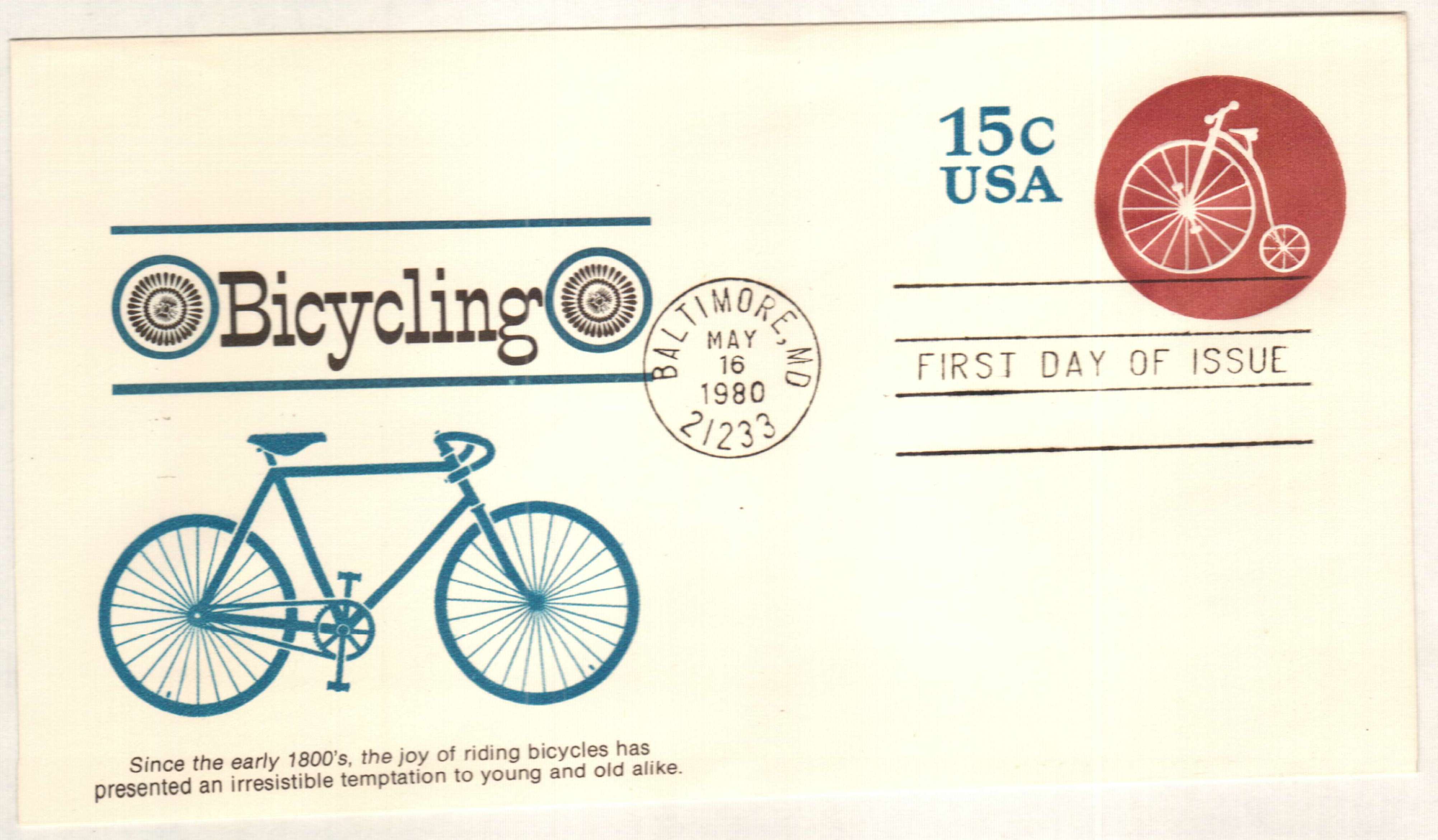

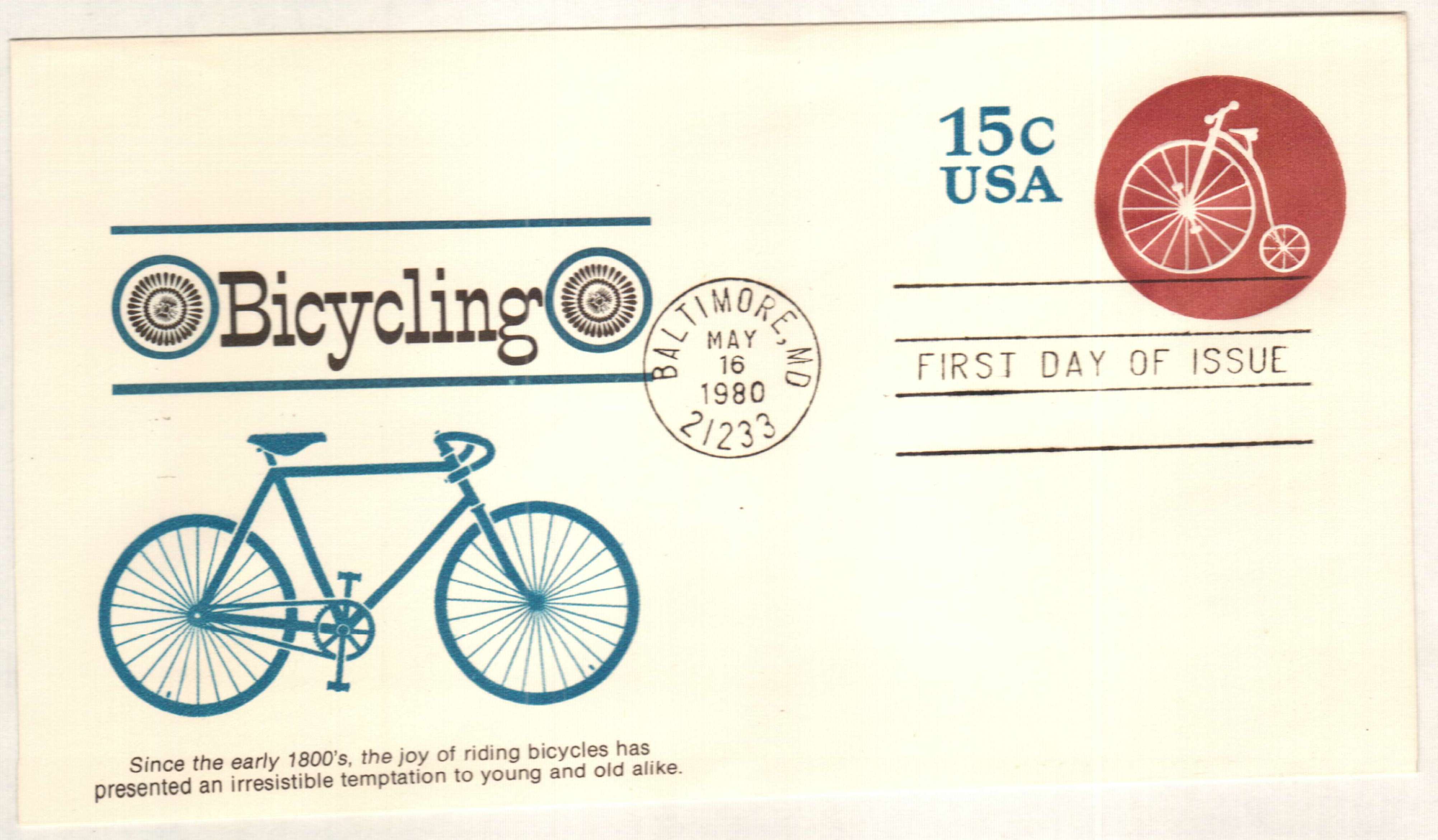

# U597 - 1980 15c Stamped Envelopes and Wrappers - Bicycle, blue & rose claret

Bicycle Mail

On July 6, 1894, a San Francisco businessman operated a short-lived bicycle mail route in San Francisco, complete with his own stamps.

The economic panic of 1893 hurt businesses across the nation, the Pullman Palace Car Company among them. As demand for their train cars declined, the company cut wages. Workers then complained of the low wages and 16-hour workdays. When the company president, George Pullman, refused to speak to the employees, they launched a boycott on June 26, 1894, led by Eugene V. Debs of the American Railway Union (ARU).

The strike brought mail delivery in the affected areas to a halt, which inspired Arthur Banta, owner of the Victor Cyclery store in Fresno, California, to take action. He set up a bicycle mail route that spanned the 210 miles between Fresno and San Francisco. The route consisted of eight relay points where riders were to remain at the ready for their deliveries. Banta estimated the route could be completed in about 18 hours each way. The service officially began on July 6, 1894. Banta ran advertisements for the route, stating a rate of 25¢ for letters to San Francisco or other locations along the way. Customers had to get the letters to his store by 10 pm in order for them to be delivered the next day.

Banta also had special diamond-shaped Bicycle Mail stamps produced for the service. These special stamps were used on covers with current US stamps from the time or on stamped envelopes. The printer produced over 800 stamps before realizing he had misspelled San Francisco as “San Fransisco.” Once he realized the error, he re-engraved the plate and printed more stamps. The service ran until July 18, when the railway strike ended. During that time, the bicycle mail service reportedly carrier 380 letters, 315 of which were stamped and 40 of which were in stamped envelopes.

There’s also a bit of controversy around these stamps. It turns out the man that engraved the die knew collectors at the time would want these stamps and covers. Banta didn’t want to pay the $5 fee to take ownership of the die. So the engraver produced a second die and defaced it, to convince Banta he’d defaced the original and couldn’t produce more stamps. It was later discovered that he went on to produce more stamps and covers without Banta’s knowledge. But when he found out, the engraver defaced the original die too.

Returning back to the Pullman strike, this tale also has an interesting connection to Labor Day

The strike ended production in the Pullman factories and resulted in a lockout. Soon, railroad workers around the country refused to switch Pullman cars. Within four days, 125,000 workers from 29 railroads stopped working, causing the companies to hire replacement workers, which vastly increased hostilities. As tensions increased, so did the violence, with workers burning a nearby building, derailing trains, blocking tracks, and threatening their replacements.

The railroads then obtained an injunction, instructing union leaders to abandon the strike and warning the workers to end the strike or be fired. When the workers and union leaders ignored the injunction, President Grover Cleveland claimed they were interfering with mail delivery and violating the Sherman Antitrust Act, threatening public safety. As a result, he sent in US Marshalls and 12,000 Army troops to suppress the workers. In all, 13 strikers were killed and 57 wounded, causing $340,000 worth of property damage.

Bicycle Mail

On July 6, 1894, a San Francisco businessman operated a short-lived bicycle mail route in San Francisco, complete with his own stamps.

The economic panic of 1893 hurt businesses across the nation, the Pullman Palace Car Company among them. As demand for their train cars declined, the company cut wages. Workers then complained of the low wages and 16-hour workdays. When the company president, George Pullman, refused to speak to the employees, they launched a boycott on June 26, 1894, led by Eugene V. Debs of the American Railway Union (ARU).

The strike brought mail delivery in the affected areas to a halt, which inspired Arthur Banta, owner of the Victor Cyclery store in Fresno, California, to take action. He set up a bicycle mail route that spanned the 210 miles between Fresno and San Francisco. The route consisted of eight relay points where riders were to remain at the ready for their deliveries. Banta estimated the route could be completed in about 18 hours each way. The service officially began on July 6, 1894. Banta ran advertisements for the route, stating a rate of 25¢ for letters to San Francisco or other locations along the way. Customers had to get the letters to his store by 10 pm in order for them to be delivered the next day.

Banta also had special diamond-shaped Bicycle Mail stamps produced for the service. These special stamps were used on covers with current US stamps from the time or on stamped envelopes. The printer produced over 800 stamps before realizing he had misspelled San Francisco as “San Fransisco.” Once he realized the error, he re-engraved the plate and printed more stamps. The service ran until July 18, when the railway strike ended. During that time, the bicycle mail service reportedly carrier 380 letters, 315 of which were stamped and 40 of which were in stamped envelopes.

There’s also a bit of controversy around these stamps. It turns out the man that engraved the die knew collectors at the time would want these stamps and covers. Banta didn’t want to pay the $5 fee to take ownership of the die. So the engraver produced a second die and defaced it, to convince Banta he’d defaced the original and couldn’t produce more stamps. It was later discovered that he went on to produce more stamps and covers without Banta’s knowledge. But when he found out, the engraver defaced the original die too.

Returning back to the Pullman strike, this tale also has an interesting connection to Labor Day

The strike ended production in the Pullman factories and resulted in a lockout. Soon, railroad workers around the country refused to switch Pullman cars. Within four days, 125,000 workers from 29 railroads stopped working, causing the companies to hire replacement workers, which vastly increased hostilities. As tensions increased, so did the violence, with workers burning a nearby building, derailing trains, blocking tracks, and threatening their replacements.

The railroads then obtained an injunction, instructing union leaders to abandon the strike and warning the workers to end the strike or be fired. When the workers and union leaders ignored the injunction, President Grover Cleveland claimed they were interfering with mail delivery and violating the Sherman Antitrust Act, threatening public safety. As a result, he sent in US Marshalls and 12,000 Army troops to suppress the workers. In all, 13 strikers were killed and 57 wounded, causing $340,000 worth of property damage.