# C20-22 - 1935 China Clippers Airmail Stamps

1937 20¢ China Clipper

Trans-Pacific Issue

China Clipper Inaugurates Trans-Pacific Airmail

Aviation in the 1920s developed at an incredible pace. Instead of the fragile wood and fabric of early biplanes, aircraft were soon being constructed of sturdy, streamlined metal propelled by increasingly light and powerful motors. As planes became more safe and reliable, people began to realize the amazing potential of flight.

US Airmail, first flown in May 1918, began regularly scheduled transcontinental flights only two years later. Commercial travel developed alongside airmail, bringing passengers to their destinations quicker and easier than ever before. But as fast as flight was progressing, the oceans still proved a formidable obstacle.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis made the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic. A year later, the famous Graf Zeppelin airship began transatlantic passenger and mail flights. International air travel was becoming a reality for the first time. Realizing the huge economic potential, airlines began developing the infrastructure necessary to make worldwide scheduled flight routes possible. It was a huge undertaking – not many countries had airfields large enough for a commercial aircraft to land, or access to the supplies and parts needed to maintain those planes.

Pan American Airways had a novel solution to bring airmail and travelers to destinations without an airfield. The company began to create a fleet of seaplanes, capable of landing anywhere with a sheltered harbor. Pan Am bought out smaller airlines in Central and South America and received landing rights and mail contracts to many countries in the area (including the US Airmail contract to Cuba).

By 1930, the company was flying along both coasts of South America as far north as Buenos Aires. However, the long-distance transpacific route remained out of the airline’s reach – a commercial seaplane capable of carrying mail and passengers across the Pacific simply didn’t exist. So the president of Pan Am, Juan Trippe, appealed to the aircraft industry to create a flying boat capable of the feat.

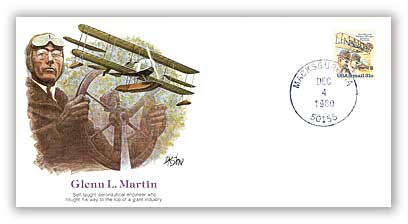

The Glenn L. Martin Company accepted Trippe’s challenge, and in 1935 built three Martin M-130 flying boats. Costing around $400,000 each, the aerodynamic, all-metal aircraft featured four 830 horsepower engines and a fuel capacity of over 4,000 gallons. Pan Am named its first M-130 the China Clipper. With a range of 3,200 miles, the airline finally had the seaplane it needed to fly mail and passengers over the Pacific!

The Glenn L. Martin Company accepted Trippe’s challenge, and in 1935 built three Martin M-130 flying boats. Costing around $400,000 each, the aerodynamic, all-metal aircraft featured four 830 horsepower engines and a fuel capacity of over 4,000 gallons. Pan Am named its first M-130 the China Clipper. With a range of 3,200 miles, the airline finally had the seaplane it needed to fly mail and passengers over the Pacific!On November 22, 1935, China Clipper left Alameda, California, carrying the first-ever transpacific airmail. Its crew included famous pilot Ed Musick and navigator Fred Noonan. (Two years later, Noonan and Amelia Earhart would disappear on their infamous attempt to cross the globe.) China Clipper had planned to fly over the incomplete San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge shortly after taking off. However, the pilot realized he wouldn’t make it over the bridge and flew under instead – narrowly avoiding a crash. The plane completed its historic 8,000-mile island-hopping journey across the Pacific on November 29, delivering 58 mailbags with more than 110,000 pieces of mail.

In 1936, Pan Am first allowed passengers on its transpacific flights. Two more Martin M-130s, the Hawaii Clipper and Philippine Clipper, began flying the same route as China Clipper. For the next few years, the three planes successfully carried passengers and millions of pieces of mail across the Pacific. However, it soon became apparent just how dangerous transoceanic flight could be.

Before the invention of radar, pilots used a compass and sea currents to navigate over the ocean. At night, the position of stars in the sky would be used as a guide. And if the weather was bad, dead reckoning (navigating from a known location) was used. The vast oceans left pilots with little margin for error – go off-route, and the plane might not have enough fuel to make it to its next destination. On July 28, 1938, Hawaii Clipper disappeared on its way to Guam from Manila. A ship noticed an oil slick along the plane’s route, but the aircraft – along with its six passengers and nine crew – were never seen again. At the time, it was the Pacific’s worst airline accident – foreshadowing the fate of the other two Martin M-130s.

With the outbreak of WWII, the remaining two M-130 flying boats were pressed into service with the Navy. While still piloted by Pan Am employees, the flying boats’ range and capacity made it a valuable asset to the military. At Wake Island, the Philippine Clipper survived repeated attacks by Japanese aircraft the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. But just over a year later, the plane was flying Navy officers from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco when it crashed into a mountain during bad weather. Of the three original M-130 seaplanes, only the China Clipper remained.

China Clipper managed to survive its service in the war. By this time, Pan Am had newer, larger models of flying boats in service across the Pacific, so the China Clipper was transferred to the less-famous Miami–Leopold transatlantic route. On January 8, 1945, it attempted to land at the Port of Spain in Trinidad and Tobago. The plane hit the water nose-first at a high speed, breaking its hull in two. The China Clipper quickly sank, taking 23 passengers and crew with it. Over its career, the famous plane had spent over 15,000 hours in the air, transporting around 3,500 passengers and 750,000 pounds of mail over the oceans.

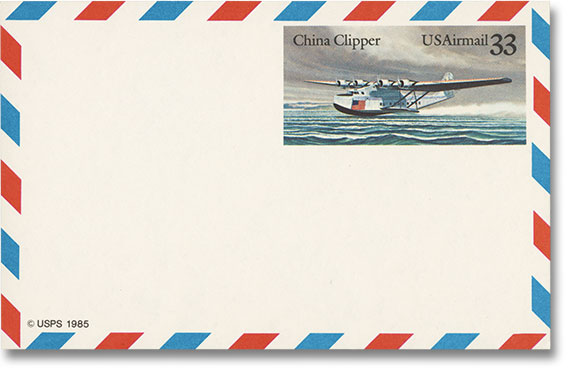

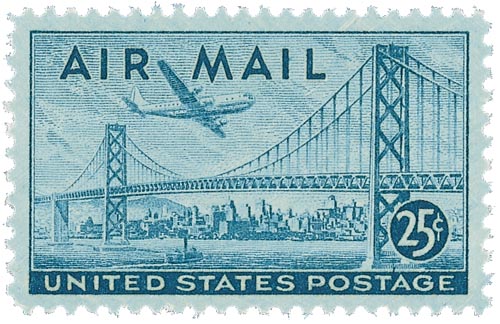

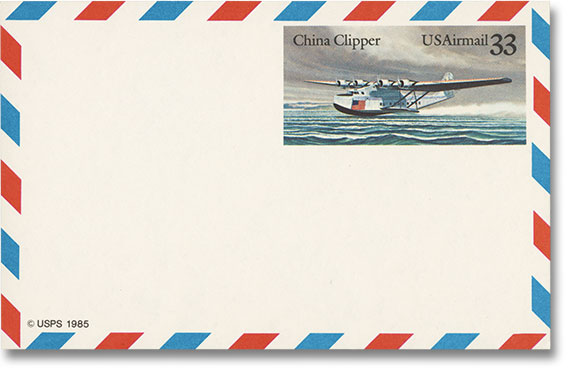

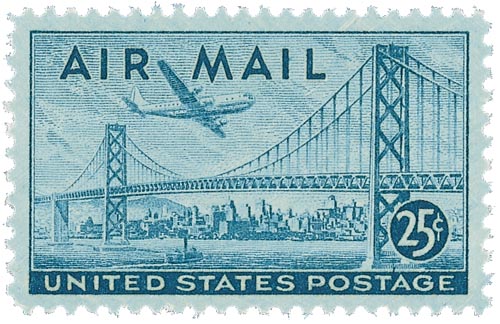

The first China Clipper Airmail stamp was issued on the day of its inaugural flight, November 22, 1935. The 25¢ denomination satisfied the rate for mail sent on one leg of the transpacific flight – from San Francisco to Hawaii, Hawaii to Guam, or Guam to Manila. A letter traveling the entire journey required 75¢ postage.

Two years later, the service was extended to Hong Kong and China. A green 20¢ and a carmine 50¢ stamp were issued for this service using the same design but minus the “November 1935” inscription (#C21-22). The addition of the China route resulted in the three stamps being nicknamed the “China Clippers.”

Click here for photos and more about the China Clipper.

1937 20¢ China Clipper

Trans-Pacific Issue

China Clipper Inaugurates Trans-Pacific Airmail

Aviation in the 1920s developed at an incredible pace. Instead of the fragile wood and fabric of early biplanes, aircraft were soon being constructed of sturdy, streamlined metal propelled by increasingly light and powerful motors. As planes became more safe and reliable, people began to realize the amazing potential of flight.

US Airmail, first flown in May 1918, began regularly scheduled transcontinental flights only two years later. Commercial travel developed alongside airmail, bringing passengers to their destinations quicker and easier than ever before. But as fast as flight was progressing, the oceans still proved a formidable obstacle.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh and his Spirit of St. Louis made the first nonstop flight across the Atlantic. A year later, the famous Graf Zeppelin airship began transatlantic passenger and mail flights. International air travel was becoming a reality for the first time. Realizing the huge economic potential, airlines began developing the infrastructure necessary to make worldwide scheduled flight routes possible. It was a huge undertaking – not many countries had airfields large enough for a commercial aircraft to land, or access to the supplies and parts needed to maintain those planes.

Pan American Airways had a novel solution to bring airmail and travelers to destinations without an airfield. The company began to create a fleet of seaplanes, capable of landing anywhere with a sheltered harbor. Pan Am bought out smaller airlines in Central and South America and received landing rights and mail contracts to many countries in the area (including the US Airmail contract to Cuba).

By 1930, the company was flying along both coasts of South America as far north as Buenos Aires. However, the long-distance transpacific route remained out of the airline’s reach – a commercial seaplane capable of carrying mail and passengers across the Pacific simply didn’t exist. So the president of Pan Am, Juan Trippe, appealed to the aircraft industry to create a flying boat capable of the feat.

The Glenn L. Martin Company accepted Trippe’s challenge, and in 1935 built three Martin M-130 flying boats. Costing around $400,000 each, the aerodynamic, all-metal aircraft featured four 830 horsepower engines and a fuel capacity of over 4,000 gallons. Pan Am named its first M-130 the China Clipper. With a range of 3,200 miles, the airline finally had the seaplane it needed to fly mail and passengers over the Pacific!

The Glenn L. Martin Company accepted Trippe’s challenge, and in 1935 built three Martin M-130 flying boats. Costing around $400,000 each, the aerodynamic, all-metal aircraft featured four 830 horsepower engines and a fuel capacity of over 4,000 gallons. Pan Am named its first M-130 the China Clipper. With a range of 3,200 miles, the airline finally had the seaplane it needed to fly mail and passengers over the Pacific!On November 22, 1935, China Clipper left Alameda, California, carrying the first-ever transpacific airmail. Its crew included famous pilot Ed Musick and navigator Fred Noonan. (Two years later, Noonan and Amelia Earhart would disappear on their infamous attempt to cross the globe.) China Clipper had planned to fly over the incomplete San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge shortly after taking off. However, the pilot realized he wouldn’t make it over the bridge and flew under instead – narrowly avoiding a crash. The plane completed its historic 8,000-mile island-hopping journey across the Pacific on November 29, delivering 58 mailbags with more than 110,000 pieces of mail.

In 1936, Pan Am first allowed passengers on its transpacific flights. Two more Martin M-130s, the Hawaii Clipper and Philippine Clipper, began flying the same route as China Clipper. For the next few years, the three planes successfully carried passengers and millions of pieces of mail across the Pacific. However, it soon became apparent just how dangerous transoceanic flight could be.

Before the invention of radar, pilots used a compass and sea currents to navigate over the ocean. At night, the position of stars in the sky would be used as a guide. And if the weather was bad, dead reckoning (navigating from a known location) was used. The vast oceans left pilots with little margin for error – go off-route, and the plane might not have enough fuel to make it to its next destination. On July 28, 1938, Hawaii Clipper disappeared on its way to Guam from Manila. A ship noticed an oil slick along the plane’s route, but the aircraft – along with its six passengers and nine crew – were never seen again. At the time, it was the Pacific’s worst airline accident – foreshadowing the fate of the other two Martin M-130s.

With the outbreak of WWII, the remaining two M-130 flying boats were pressed into service with the Navy. While still piloted by Pan Am employees, the flying boats’ range and capacity made it a valuable asset to the military. At Wake Island, the Philippine Clipper survived repeated attacks by Japanese aircraft the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. But just over a year later, the plane was flying Navy officers from Pearl Harbor to San Francisco when it crashed into a mountain during bad weather. Of the three original M-130 seaplanes, only the China Clipper remained.

China Clipper managed to survive its service in the war. By this time, Pan Am had newer, larger models of flying boats in service across the Pacific, so the China Clipper was transferred to the less-famous Miami–Leopold transatlantic route. On January 8, 1945, it attempted to land at the Port of Spain in Trinidad and Tobago. The plane hit the water nose-first at a high speed, breaking its hull in two. The China Clipper quickly sank, taking 23 passengers and crew with it. Over its career, the famous plane had spent over 15,000 hours in the air, transporting around 3,500 passengers and 750,000 pounds of mail over the oceans.

The first China Clipper Airmail stamp was issued on the day of its inaugural flight, November 22, 1935. The 25¢ denomination satisfied the rate for mail sent on one leg of the transpacific flight – from San Francisco to Hawaii, Hawaii to Guam, or Guam to Manila. A letter traveling the entire journey required 75¢ postage.

Two years later, the service was extended to Hong Kong and China. A green 20¢ and a carmine 50¢ stamp were issued for this service using the same design but minus the “November 1935” inscription (#C21-22). The addition of the China route resulted in the three stamps being nicknamed the “China Clippers.”

Click here for photos and more about the China Clipper.