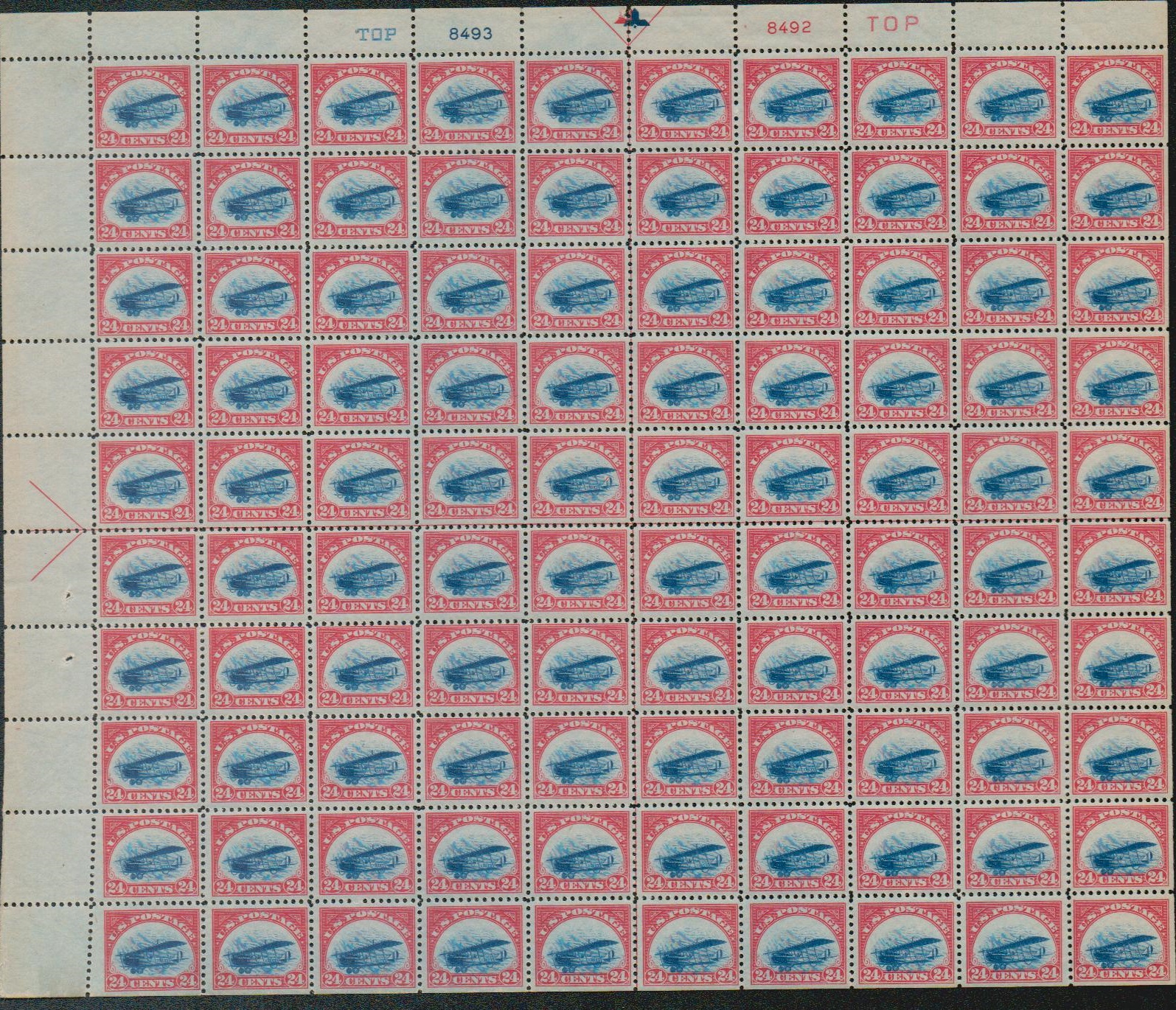

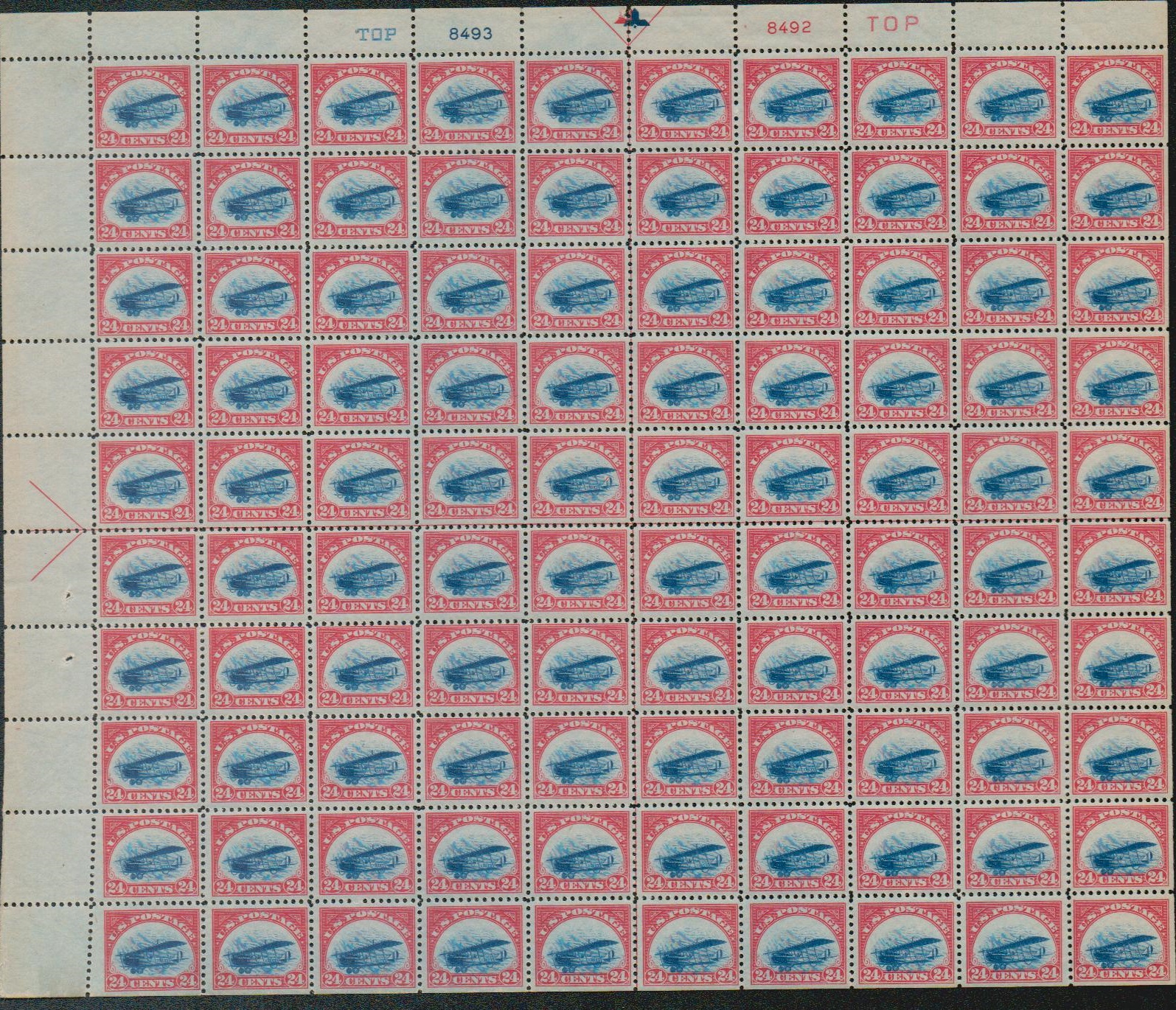

# C2 - 1918 16c Curtiss Jenny, green

1918 16¢ Curtiss Jenny

City: Washington, DC

Quantity: 3,793,887

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat plate printing

Perforations: 11

Color: Green

America Issues First Airmail Stamp

The possibility of airmail delivery had been debated and dismissed for nearly a decade, so it came as a surprise to many when Postmaster General Burleson suddenly announced that service would begin between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. The year was 1918 and the world was at war. Critics argued that every available resource – including planes and pilots – was needed to win the war.

However, Burleson brokered a deal with the War Department on March 1, 1918. Under this arrangement, the Postal Department would handle their traditional tasks and the military would provide the planes and pilots. Americans would have a rapid system of mail transportation, and military pilots would receive badly needed flight training. However, the War Department didn’t notify the Army Air Service of its new assignment until May 3, 1918.

Major Reuben H. Fleet, an Army executive officer in charge of planning instruction, was placed in charge of making the necessary arrangements. The task was overwhelming. Fleet faced a shortage of planes, pilots, airfields, and aircraft mechanics. None of the available planes were capable of flying the proposed route. “The best plane we have is the Curtiss JN-4D Jenny, and it will fly only an hour and twenty minutes. Its maximum range is 88 miles at a cruising speed of 66 miles per hour,” Fleet advised.

The Postal Department stood firm in spite of the logistical and safety issues. The first regularly scheduled U.S. airmail flight was to leave Washington, D.C., on May 15th. Major Fleet had just two weeks to plan a major revolution in communication.

By all accounts, the 24¢ fee for airmail transportation with Special Delivery was an arbitrary decision. At eight times the regular first class rate, the amount outraged several officials. The figure was equal to more than $12 in modern wages, and the service only shaved a few hours off existing transportation time.

As late as April 25, 1918, officials denied that a special stamp would be issued to frank airmail letters. The public was told that regular postage stamps would be valid for airmail delivery. However, available stamps didn’t include a 24¢ denomination. A decision was made to produce a patriotic red, white, and blue stamp to inaugurate the revolutionary new service and lift war-weary spirits. It would be the first bi-colored U.S. stamp issued since the 1901 Pan-American Exposition commemoratives.

The formal request for a new 24¢ airmail stamp reached the Bureau of Engraving and Printing less than two weeks before the first scheduled flight. The understaffed BEP worked around the clock to design, engrave, and print the first U.S. airmail stamps.

Using a War Department photo, BEP veteran Clair Aubrey Huston designed a blue vignette featuring the Curtiss Jenny JN-4 surrounded by a red frame. Although the precise date isn’t recorded, the actual engraving began around May 9, 1918. With the tight deadline met, the 24¢ airmail stamps were placed on sale slightly ahead of time late Monday afternoon – May 13, 1918.

Meanwhile, Fleet began the task of securing a fleet of airplanes, selecting pilots, and untangling a host of other details, including the flight plan. One plane was to depart New York and fly south at the same time a second plane flew north from Washington, D.C. The planes were to meet in Philadelphia to exchange mailbags and refuel before returning home.

On May 15, a crowd of several hundred gathered at Washington’s Polo Grounds to witness history being made. After carefully reviewing the route to Philadelphia on Fleet’s map – a photo opportunity that would become more ironic as the day progressed – Lt. George Boyle climbed inside the Jenny. His bags contained 5,500 letters destined to fly on the first airmail route in U.S. history.

As President Woodrow Wilson looked on with a crowd of dignitaries, mechanics tried to start Boyle’s plane. The propeller turned but the engine wouldn’t start. After four attempts, mechanics checked the gas tank and realized the plane was out of fuel. Furthermore, there was no gas on the field, so mechanics quickly siphoned fuel out of nearby planes. Boyle flew off for his journey to Philadelphia at 11:46 a.m. – 45 minutes late and barely clearing nearby trees.

Hours later, officials would learn that Boyle had flown in the wrong direction and crashed his plane. Instructed to follow the train tracks north, Boyle had become disoriented and used a southeastern branch of the track as his guide. Although Lt. Boyle escaped injury, Jenny No. 38262 was lying upside down in a field near Otto Praeger’s country home. The mailbags aboard Boyle’s plane were quietly brought back to Washington, D.C., and flown to Philadelphia and New York City the following day.

Meanwhile, Lt. Torrey Webb had left New York and arrived safely in Philadelphia. His mailbags were transferred to the waiting plane of Lt. James Edgerton, who arrived in Washington, D.C., at 2:20 p.m. After two weeks of intense preparation and high drama, America’s first airmail service was established.

In the months that followed, pioneering aviators expanded airmail service, flying by the seat of their pants over the treacherous Allegheny Mountains to Chicago and eventually the west coast. The cost of sending an airmail letter dropped dramatically in the early months of the service – to 16¢ in July to just 6¢ in December. (Special Delivery service became optional with the December rate.)

With each decrease, a new single color stamp was issued using the same design as the 24¢ Jenny. Scott Catalog assigned numbers to the set of three 1918 airmail stamps based on denomination rather than chronology, which unfortunately created confusion among collectors. The first U.S. airmail stamp (24¢) was issued as U.S. #C3, while the last 1918 airmail stamp is identified as #C1.

1918 16¢ Curtiss Jenny

City: Washington, DC

Quantity: 3,793,887

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat plate printing

Perforations: 11

Color: Green

America Issues First Airmail Stamp

The possibility of airmail delivery had been debated and dismissed for nearly a decade, so it came as a surprise to many when Postmaster General Burleson suddenly announced that service would begin between New York City, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. The year was 1918 and the world was at war. Critics argued that every available resource – including planes and pilots – was needed to win the war.

However, Burleson brokered a deal with the War Department on March 1, 1918. Under this arrangement, the Postal Department would handle their traditional tasks and the military would provide the planes and pilots. Americans would have a rapid system of mail transportation, and military pilots would receive badly needed flight training. However, the War Department didn’t notify the Army Air Service of its new assignment until May 3, 1918.

Major Reuben H. Fleet, an Army executive officer in charge of planning instruction, was placed in charge of making the necessary arrangements. The task was overwhelming. Fleet faced a shortage of planes, pilots, airfields, and aircraft mechanics. None of the available planes were capable of flying the proposed route. “The best plane we have is the Curtiss JN-4D Jenny, and it will fly only an hour and twenty minutes. Its maximum range is 88 miles at a cruising speed of 66 miles per hour,” Fleet advised.

The Postal Department stood firm in spite of the logistical and safety issues. The first regularly scheduled U.S. airmail flight was to leave Washington, D.C., on May 15th. Major Fleet had just two weeks to plan a major revolution in communication.

By all accounts, the 24¢ fee for airmail transportation with Special Delivery was an arbitrary decision. At eight times the regular first class rate, the amount outraged several officials. The figure was equal to more than $12 in modern wages, and the service only shaved a few hours off existing transportation time.

As late as April 25, 1918, officials denied that a special stamp would be issued to frank airmail letters. The public was told that regular postage stamps would be valid for airmail delivery. However, available stamps didn’t include a 24¢ denomination. A decision was made to produce a patriotic red, white, and blue stamp to inaugurate the revolutionary new service and lift war-weary spirits. It would be the first bi-colored U.S. stamp issued since the 1901 Pan-American Exposition commemoratives.

The formal request for a new 24¢ airmail stamp reached the Bureau of Engraving and Printing less than two weeks before the first scheduled flight. The understaffed BEP worked around the clock to design, engrave, and print the first U.S. airmail stamps.

Using a War Department photo, BEP veteran Clair Aubrey Huston designed a blue vignette featuring the Curtiss Jenny JN-4 surrounded by a red frame. Although the precise date isn’t recorded, the actual engraving began around May 9, 1918. With the tight deadline met, the 24¢ airmail stamps were placed on sale slightly ahead of time late Monday afternoon – May 13, 1918.

Meanwhile, Fleet began the task of securing a fleet of airplanes, selecting pilots, and untangling a host of other details, including the flight plan. One plane was to depart New York and fly south at the same time a second plane flew north from Washington, D.C. The planes were to meet in Philadelphia to exchange mailbags and refuel before returning home.

On May 15, a crowd of several hundred gathered at Washington’s Polo Grounds to witness history being made. After carefully reviewing the route to Philadelphia on Fleet’s map – a photo opportunity that would become more ironic as the day progressed – Lt. George Boyle climbed inside the Jenny. His bags contained 5,500 letters destined to fly on the first airmail route in U.S. history.

As President Woodrow Wilson looked on with a crowd of dignitaries, mechanics tried to start Boyle’s plane. The propeller turned but the engine wouldn’t start. After four attempts, mechanics checked the gas tank and realized the plane was out of fuel. Furthermore, there was no gas on the field, so mechanics quickly siphoned fuel out of nearby planes. Boyle flew off for his journey to Philadelphia at 11:46 a.m. – 45 minutes late and barely clearing nearby trees.

Hours later, officials would learn that Boyle had flown in the wrong direction and crashed his plane. Instructed to follow the train tracks north, Boyle had become disoriented and used a southeastern branch of the track as his guide. Although Lt. Boyle escaped injury, Jenny No. 38262 was lying upside down in a field near Otto Praeger’s country home. The mailbags aboard Boyle’s plane were quietly brought back to Washington, D.C., and flown to Philadelphia and New York City the following day.

Meanwhile, Lt. Torrey Webb had left New York and arrived safely in Philadelphia. His mailbags were transferred to the waiting plane of Lt. James Edgerton, who arrived in Washington, D.C., at 2:20 p.m. After two weeks of intense preparation and high drama, America’s first airmail service was established.

In the months that followed, pioneering aviators expanded airmail service, flying by the seat of their pants over the treacherous Allegheny Mountains to Chicago and eventually the west coast. The cost of sending an airmail letter dropped dramatically in the early months of the service – to 16¢ in July to just 6¢ in December. (Special Delivery service became optional with the December rate.)

With each decrease, a new single color stamp was issued using the same design as the 24¢ Jenny. Scott Catalog assigned numbers to the set of three 1918 airmail stamps based on denomination rather than chronology, which unfortunately created confusion among collectors. The first U.S. airmail stamp (24¢) was issued as U.S. #C3, while the last 1918 airmail stamp is identified as #C1.