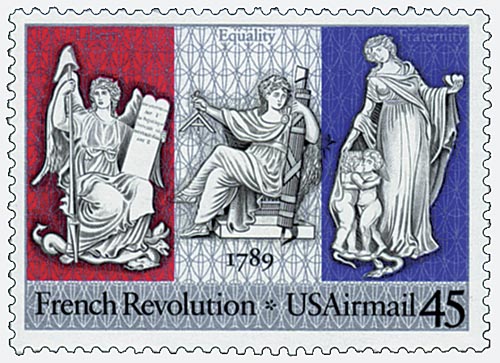

# C120 - 1989 45c French Revolution Joint Issue with France

1989 45¢ French Revolution Bicentennial

First City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 38,532,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforation: 11 ½ x 11

Beginning Of The French Revolution

On July 14, 1789, revolutionaries stormed the Bastille in Paris, marking the start of the decade-long French Revolution.

In 1370, the people of Paris built a bastide (fortification), to protect from a British attack. Over time it became an independent fort and its name became Bastille. In the 17th century it was used as a state prison, housing upper-class felons and spies. Many were imprisoned there without a trial as ordered by the king.

By the time King Louis XVI took the throne, France was heading toward revolution. The country was in the midst of an economic crisis, due to its intervention in the American Revolution as well as a failing tax system. This, coupled with spreading food shortages, led to nationwide resentment and anger toward the king.

On June 17, 1789, the National Assembly was formed and called for the creation of a French constitution. At first, King Louis XVI seemed to support the idea, legalizing the National Assembly. However, he then surrounded Paris with troops and fired Jacques Necker, a popular state minister that had supported reforms.

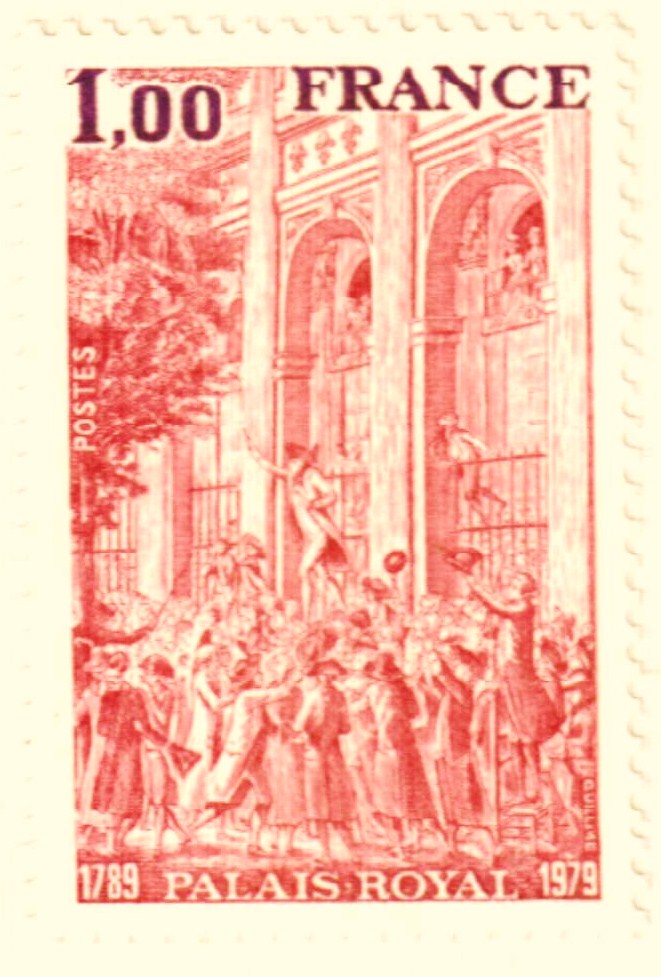

Soon revolutionary leaders began to rise and encouraged rioting in the streets of Paris. At the Palais-Royal, one such leader, Camille Desmoulins, proclaimed that, “This very night all the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ de Mars to massacre us all; one resource is left; to take arms!”

Meanwhile, the military governor of the Bastille, Bernard-René de Launay, worried that the fortress might be one of the revolutionaries’ targets and requested reinforcements. A company of Swiss mercenaries was then brought in to aid the 82 French soldiers there. On July 12 Royal authorities worried that the revolutionaries might attack the Paris Arsenal, so they transferred 250 barrels of gunpowder to the Bastille.

Of the seven inmates at the Bastille at that time was the Marquis de Sade. When he was transferred to an insane asylum, he shouted out his window, “They are massacring the prisoners; you must come and free them.”

On July 13 revolutionaries approached the Bastille with muskets and began firing on Lunay’s soldiers. Then that evening mobs of revolutionaries stormed the Paris Arsenal and other armories, collecting thousands of muskets.

At dawn on the morning of July 14, 1789, a huge crowd armed with muskets, swords, and other weapons assembled around the Bastille. Launay invited some of the revolutionary leaders to meet with him, but he refused to surrender the fort. He then met with a second group of leaders and promised not to fire on the crowd. As a sign of good faith he even showed them that the cannons weren’t loaded. However, this had the opposite effect, angering the crowd and inciting a group of men to climb one of the fort’s walls and lower a drawbridge. Within minutes, 300 revolutionaries stormed the fort. Those outside then attempted to lower another drawbridge but came under fire and 100 were killed or wounded.

While Launay held the fort for most of the day, more and more people arrived to support the revolutionaries, including French army deserters. These soldiers used the smoke from fires to conceal five cannons they’d brought in and aimed at the Bastille. Launay could not longer hold the fort and waved a white flag of surrender. He and his men were taken prisoner, the fort’s cannons and gunpowder were seized, and the seven prisoners were freed.

The storming of the Bastille marked the start of the French Revolution. About four-fifths of the French Army joined the revolutionaries in taking control of Paris and the French countryside. They eventually forced King Louis XVI to accept their constitutional government and later sent him and his wife to the guillotine for treason. The Bastille was then torn down under the new government.

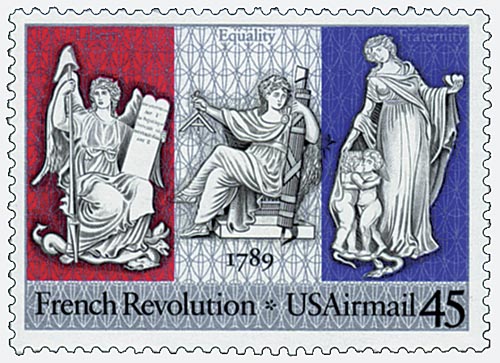

1989 45¢ French Revolution Bicentennial

First City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 38,532,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforation: 11 ½ x 11

Beginning Of The French Revolution

On July 14, 1789, revolutionaries stormed the Bastille in Paris, marking the start of the decade-long French Revolution.

In 1370, the people of Paris built a bastide (fortification), to protect from a British attack. Over time it became an independent fort and its name became Bastille. In the 17th century it was used as a state prison, housing upper-class felons and spies. Many were imprisoned there without a trial as ordered by the king.

By the time King Louis XVI took the throne, France was heading toward revolution. The country was in the midst of an economic crisis, due to its intervention in the American Revolution as well as a failing tax system. This, coupled with spreading food shortages, led to nationwide resentment and anger toward the king.

On June 17, 1789, the National Assembly was formed and called for the creation of a French constitution. At first, King Louis XVI seemed to support the idea, legalizing the National Assembly. However, he then surrounded Paris with troops and fired Jacques Necker, a popular state minister that had supported reforms.

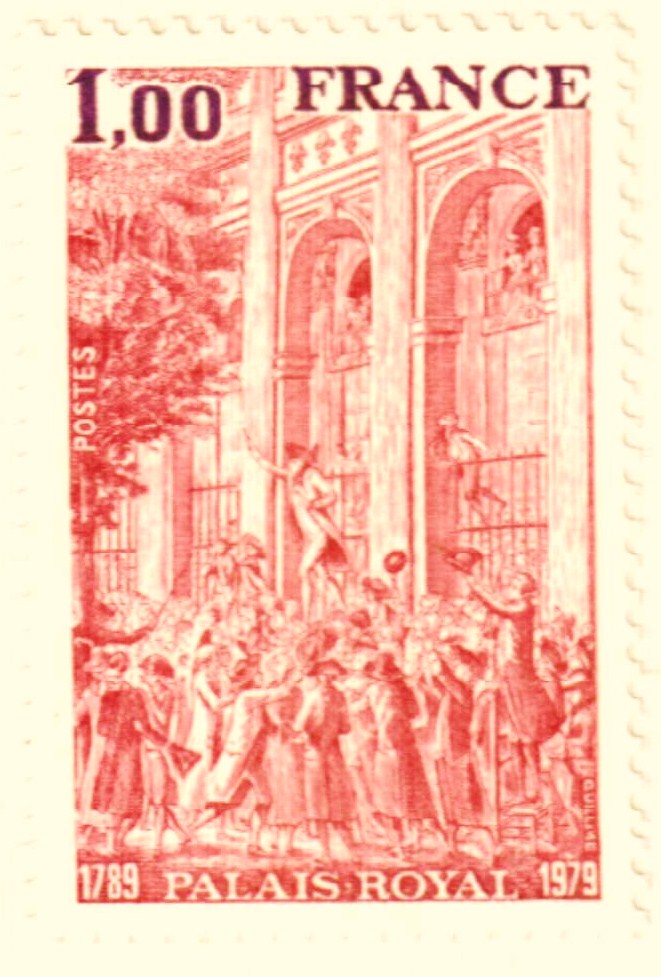

Soon revolutionary leaders began to rise and encouraged rioting in the streets of Paris. At the Palais-Royal, one such leader, Camille Desmoulins, proclaimed that, “This very night all the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ de Mars to massacre us all; one resource is left; to take arms!”

Meanwhile, the military governor of the Bastille, Bernard-René de Launay, worried that the fortress might be one of the revolutionaries’ targets and requested reinforcements. A company of Swiss mercenaries was then brought in to aid the 82 French soldiers there. On July 12 Royal authorities worried that the revolutionaries might attack the Paris Arsenal, so they transferred 250 barrels of gunpowder to the Bastille.

Of the seven inmates at the Bastille at that time was the Marquis de Sade. When he was transferred to an insane asylum, he shouted out his window, “They are massacring the prisoners; you must come and free them.”

On July 13 revolutionaries approached the Bastille with muskets and began firing on Lunay’s soldiers. Then that evening mobs of revolutionaries stormed the Paris Arsenal and other armories, collecting thousands of muskets.

At dawn on the morning of July 14, 1789, a huge crowd armed with muskets, swords, and other weapons assembled around the Bastille. Launay invited some of the revolutionary leaders to meet with him, but he refused to surrender the fort. He then met with a second group of leaders and promised not to fire on the crowd. As a sign of good faith he even showed them that the cannons weren’t loaded. However, this had the opposite effect, angering the crowd and inciting a group of men to climb one of the fort’s walls and lower a drawbridge. Within minutes, 300 revolutionaries stormed the fort. Those outside then attempted to lower another drawbridge but came under fire and 100 were killed or wounded.

While Launay held the fort for most of the day, more and more people arrived to support the revolutionaries, including French army deserters. These soldiers used the smoke from fires to conceal five cannons they’d brought in and aimed at the Bastille. Launay could not longer hold the fort and waved a white flag of surrender. He and his men were taken prisoner, the fort’s cannons and gunpowder were seized, and the seven prisoners were freed.

The storming of the Bastille marked the start of the French Revolution. About four-fifths of the French Army joined the revolutionaries in taking control of Paris and the French countryside. They eventually forced King Louis XVI to accept their constitutional government and later sent him and his wife to the guillotine for treason. The Bastille was then torn down under the new government.