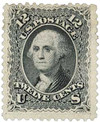

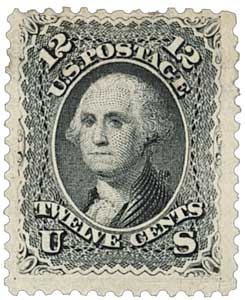

# 97 - 1867 12c Washington, black

U.S. #97

Series of 1867 12¢ Washington

“F” Grill

Earliest Known Use: May 27, 1868

Quantity issued: 2,600,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Black

Grills were made by embossing the stamp, breaking paper fibers, and allowing canceling ink to soak deeply into the paper. This made it difficult to remove cancels and reuse stamps. Charles Steel, who oversaw postage stamp production in the 1860s, patented the grilling method. It was used nine short years – 1867 to 1875. Grilling resulted in some of the greatest U.S. stamp rarities, including the legendary “Z” Grill U.S. #85A.

Series of 1867

Grills are classified by the dimensions of the grill pattern and are measured in millimeters or by counting the number of grill points. There are eleven major classifications.

“A” Grill Covers the entire stamp

“B” Grill 18x15mm (22x18pts)

“C” Grill 13x16mm (16-17x18-21pts)

“D” Grill 12x14mm (15-17-18pts)

“Z” Grill 11x14mm (13-14x18pts)

“E” Grill 11x13mm (14x15-17pts)

“F” Grill 9x13mm (11-12x15-17pts)

“G” Grill 9 ½ x9mm (12x11-11 ½ pts)

“H” Grill 10x12mm (11-13x14-16pts)

“I” Grill 8 ½ x10mm (10x11x10-13pts)

“J” Grill 7x9 ½ mm (10x12pts)

The letters that classify the various grill types do not denote the size, shape, or appearance of the grills. Rather, they simply indicate the order in which they were discovered.

The exception to the rule is the “Z” grill, which was identified by William L. Stevenson. Stevenson could not decide to which family of grills this particular type belonged. Nor did he know which other families it preceded or followed and so he designated it as “Z Grill,” where “Z” signifies the unknown.

Visible in general from the back of the stamp only, grills may also be felt by lightly running a fingertip over the surface. Depending on which type of roller was used, the pattern may be “points up” or a “points down.” The ridges on an indented roller force the paper into the recesses, creating raised points, while a roller with raised pyramids will cause the points to be forced down into the paper, forming a series of depressions.

The United States was the first country to issue grilled stamps and was the only country to do so until the mid-1870s, when Peru also began using grills. The National Bank Note Company was responsible for producing both countries’ stamps.

On October 3, 1789 and 1863, two sitting presidents called on Americans to celebrate a day of Thanksgiving in November.

Though colonists had held harvest celebrations of thanks since the 1620s, it wasn’t an official holiday celebrated everywhere. That changed in 1789. On September 25, Elias Boudinot presented a resolution to the House of Representatives asking that President Washington “recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer… [for] the many signal favors of Almighty God.”

Congress approved the resolution and appointed a committee to approach Washington. Washington agreed and issued his proclamation on October 3. In it, he asked all Americans to observe November 26 as a day to give thanks to God for their victory in the Revolution as well as their establishment of a Constitution and government. He then gave it to the governors of each state and asked them to publish it for all to see.

In the years that followed, Presidents John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations, but none were permanent. In 1817, New York officially established an annual Thanksgiving holiday. Other northern states followed suit, though they weren’t all on the same day.

Sarah Josepha Hale (famous for the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”) began a rigorous campaign in 1827 to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. She published articles and wrote letters to countless politicians, to no avail. Finally, in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln received one of her letters and was inspired. On October 3, he issued his own proclamation, establishing the last Thursday of November as a day of Thanksgiving. In particular to pray for those who lost loved ones in the war and to “heal the wounds of the nation.”

Thanksgiving continued to be celebrated on last Thursday of November until 1939, when President Franklin Roosevelt moved it up a week to increase retail sales during the Great Depression. Americans were outraged and dubbed it “Franksgiving.” Two years later he reversed his policy and signed a bill making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November, as it has remained ever since.

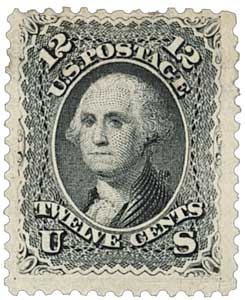

U.S. #97

Series of 1867 12¢ Washington

“F” Grill

Earliest Known Use: May 27, 1868

Quantity issued: 2,600,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Black

Grills were made by embossing the stamp, breaking paper fibers, and allowing canceling ink to soak deeply into the paper. This made it difficult to remove cancels and reuse stamps. Charles Steel, who oversaw postage stamp production in the 1860s, patented the grilling method. It was used nine short years – 1867 to 1875. Grilling resulted in some of the greatest U.S. stamp rarities, including the legendary “Z” Grill U.S. #85A.

Series of 1867

Grills are classified by the dimensions of the grill pattern and are measured in millimeters or by counting the number of grill points. There are eleven major classifications.

“A” Grill Covers the entire stamp

“B” Grill 18x15mm (22x18pts)

“C” Grill 13x16mm (16-17x18-21pts)

“D” Grill 12x14mm (15-17-18pts)

“Z” Grill 11x14mm (13-14x18pts)

“E” Grill 11x13mm (14x15-17pts)

“F” Grill 9x13mm (11-12x15-17pts)

“G” Grill 9 ½ x9mm (12x11-11 ½ pts)

“H” Grill 10x12mm (11-13x14-16pts)

“I” Grill 8 ½ x10mm (10x11x10-13pts)

“J” Grill 7x9 ½ mm (10x12pts)

The letters that classify the various grill types do not denote the size, shape, or appearance of the grills. Rather, they simply indicate the order in which they were discovered.

The exception to the rule is the “Z” grill, which was identified by William L. Stevenson. Stevenson could not decide to which family of grills this particular type belonged. Nor did he know which other families it preceded or followed and so he designated it as “Z Grill,” where “Z” signifies the unknown.

Visible in general from the back of the stamp only, grills may also be felt by lightly running a fingertip over the surface. Depending on which type of roller was used, the pattern may be “points up” or a “points down.” The ridges on an indented roller force the paper into the recesses, creating raised points, while a roller with raised pyramids will cause the points to be forced down into the paper, forming a series of depressions.

The United States was the first country to issue grilled stamps and was the only country to do so until the mid-1870s, when Peru also began using grills. The National Bank Note Company was responsible for producing both countries’ stamps.

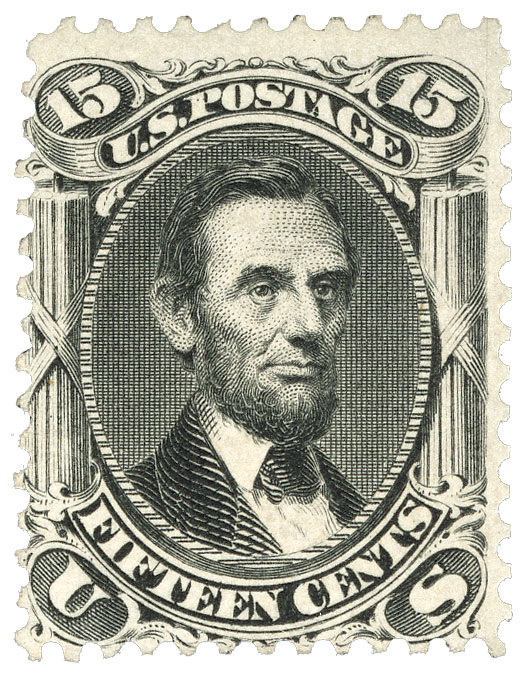

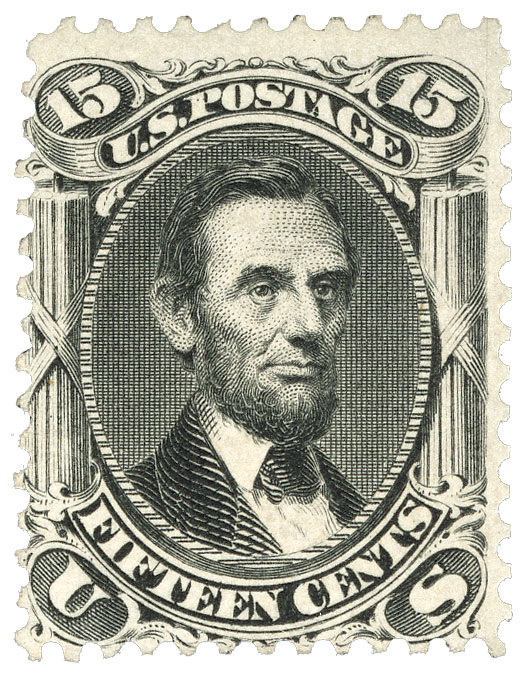

On October 3, 1789 and 1863, two sitting presidents called on Americans to celebrate a day of Thanksgiving in November.

Though colonists had held harvest celebrations of thanks since the 1620s, it wasn’t an official holiday celebrated everywhere. That changed in 1789. On September 25, Elias Boudinot presented a resolution to the House of Representatives asking that President Washington “recommend to the people of the United States a day of public thanksgiving and prayer… [for] the many signal favors of Almighty God.”

Congress approved the resolution and appointed a committee to approach Washington. Washington agreed and issued his proclamation on October 3. In it, he asked all Americans to observe November 26 as a day to give thanks to God for their victory in the Revolution as well as their establishment of a Constitution and government. He then gave it to the governors of each state and asked them to publish it for all to see.

In the years that followed, Presidents John Adams and James Madison issued similar proclamations, but none were permanent. In 1817, New York officially established an annual Thanksgiving holiday. Other northern states followed suit, though they weren’t all on the same day.

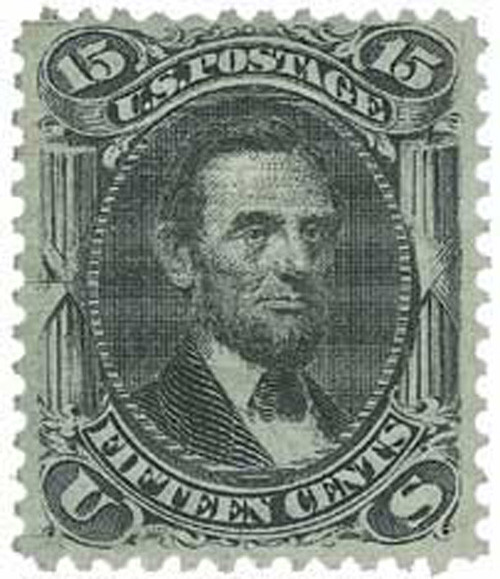

Sarah Josepha Hale (famous for the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”) began a rigorous campaign in 1827 to make Thanksgiving a national holiday. She published articles and wrote letters to countless politicians, to no avail. Finally, in 1863, at the height of the Civil War, President Lincoln received one of her letters and was inspired. On October 3, he issued his own proclamation, establishing the last Thursday of November as a day of Thanksgiving. In particular to pray for those who lost loved ones in the war and to “heal the wounds of the nation.”

Thanksgiving continued to be celebrated on last Thursday of November until 1939, when President Franklin Roosevelt moved it up a week to increase retail sales during the Great Depression. Americans were outraged and dubbed it “Franksgiving.” Two years later he reversed his policy and signed a bill making Thanksgiving the fourth Thursday of November, as it has remained ever since.