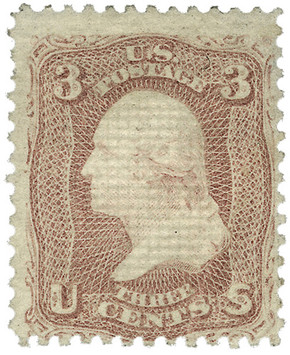

U.S. #83

George Washington

- Only stamp embossed with the “C” grill

- Grill measures 16-17 points by 18-21 points

- Last of the three “points up” grilled stamps

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: 1867

Value: 3c

Printed by: National Bank Note Co.

Quantity printed: 300,000 (estimated)

Format: Printed in sheets of 200 stamps, divided into vertical panes of 100 each

Printing Method: Engraving

Perforations: 12

Color: Rose

Earliest Documented Use: November 16th, 1867

Why the stamp was issued: The stamp paid the half-ounce domestic rate

About the printing: The design was engraved on a die – a small, flat piece of steel. The design was copied to a transfer roll – a blank roll of steel. Several impressions or “reliefs” were made on the roll. The reliefs were transferred to the plate – a large, flat piece of steel from which the stamps were printed. The grilling process was applied to the stamp after printing.

About the design: The image of Washington is based on a sculpture by Jean Antoine Houdon.

About the series of 1867: Grills were introduced because the U.S. Post Office department was worried about the removal of cancellations, allowing for fraudulent reuse of a stamp. Grills were made by embossing the stamp with a pattern to break down paper fibers, allowing cancellation ink to soak deeply into the paper. This made it impossible to remove cancels, as even regular pen ink, used to manually cancel stamps at smaller post offices, would penetrate the fibers.

There were several proposals for different ways to solve the problem. Charles Steel, who oversaw stamp production at the National Bank Note Company in the 1860s, developed and patented the grilling method. He was granted a patent for the process on October 22, 1867. Steel also saw the process as helping stamps adhere better to mail.

According to Steel’s patent, “The object of my invention is to produce a stamp which shall stick better than usual, and which it shall be impossible to fraudulently remove and use again.” Steel’s simple machine used a roller pitted with either small depressions or small raised pyramids to break fibers in the stamp paper. The rollers with depressions created a “points up” pattern while those with raised pyramids made a “points down” pattern.

The United States was the first country to issue grilled stamps and was the only country to do so until the mid-1870s, when Peru also began using grills. The National Bank Note Company was responsible for producing both countries’ stamps.

Grills were used for only nine years – 1867 to 1875, encompassing the 1869 Pictorial Series (#112-22) and the 1870-71 Bank Notes (#134-44). The National Bank Note Company attempted to find the perfect grill size by experimenting with various versions. The large A, B, and C grills weakened the paper too much. As time went on, the rollers were ground down to produce smaller-sized grills that would prevent the stamp from tearing easily, but wouldn’t let the ink penetrate the paper. That resulted in grills too weak to do the job. There was also the issue of extra expense, plus, the reuse of stamps wasn’t as prevalent as postal authorities feared. This historic postal era had come to an end.

In 1916, William L. Stevenson measured all known grill sizes and categorized them. He gave each a letter from A to J. The exception was the “Z” grill, as he was unsure to which grill family it belonged. Nor did he know which family it preceded or followed, so he used the letter “Z” to signify the unknown. It differs from other grill patterns because the tiny ridges on each peak are oriented horizontally instead of vertically.

Grills are classified by the dimensions of the grill pattern and are measured in millimeters or by counting the number of grill points. There are eleven major classifications.

“A” Grill Covers the entire stamp

“B” Grill 18x15mm (22x18pts)

“C” Grill 13x16mm (16-17x18-21pts)

“D” Grill 12x14mm (15-17-18pts)

“Z” Grill 11x14mm (14-15x17-18pts)

“E” Grill 11x13mm (14x15-17pts)

“F” Grill 9x13mm (11-12x15-17pts)

“G” Grill 9½ x9mm (12x11-11 ½ pts)

“H” Grill 10x12mm (11-13x14-16pts)

“I” Grill 8½ x10mm (10x11x10-13pts)

“J” Grill 7x9 ½ mm (10x12pts)

The letters classifying the various grill types do not denote the size, shape, or appearance of the grills. They indicate the order in which each was discovered.

Mostly visible from the back of the stamp only, grills may be felt by lightly running a fingertip over the surface. Depending on which roller was used, the pattern is “points up” or “points down.” The ridges on an indented roller force the paper into the recesses, creating raised points, while a roller with raised pyramids will cause the points to be forced down into the paper, forming a series of depressions.

Grilling resulted in some of the greatest U.S. stamp rarities, including the legendary 1c “Z” Grill (U.S. #85A) owned by Mystic Stamp Company for several years.

History the stamp represents: The “C” grill was rejected after a low quantity was issued, because it covered a large portion of the stamp and weakened it too much. This grill was the last of the “points up” grills.

U.S. #83

George Washington

- Only stamp embossed with the “C” grill

- Grill measures 16-17 points by 18-21 points

- Last of the three “points up” grilled stamps

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: 1867

Value: 3c

Printed by: National Bank Note Co.

Quantity printed: 300,000 (estimated)

Format: Printed in sheets of 200 stamps, divided into vertical panes of 100 each

Printing Method: Engraving

Perforations: 12

Color: Rose

Earliest Documented Use: November 16th, 1867

Why the stamp was issued: The stamp paid the half-ounce domestic rate

About the printing: The design was engraved on a die – a small, flat piece of steel. The design was copied to a transfer roll – a blank roll of steel. Several impressions or “reliefs” were made on the roll. The reliefs were transferred to the plate – a large, flat piece of steel from which the stamps were printed. The grilling process was applied to the stamp after printing.

About the design: The image of Washington is based on a sculpture by Jean Antoine Houdon.

About the series of 1867: Grills were introduced because the U.S. Post Office department was worried about the removal of cancellations, allowing for fraudulent reuse of a stamp. Grills were made by embossing the stamp with a pattern to break down paper fibers, allowing cancellation ink to soak deeply into the paper. This made it impossible to remove cancels, as even regular pen ink, used to manually cancel stamps at smaller post offices, would penetrate the fibers.

There were several proposals for different ways to solve the problem. Charles Steel, who oversaw stamp production at the National Bank Note Company in the 1860s, developed and patented the grilling method. He was granted a patent for the process on October 22, 1867. Steel also saw the process as helping stamps adhere better to mail.

According to Steel’s patent, “The object of my invention is to produce a stamp which shall stick better than usual, and which it shall be impossible to fraudulently remove and use again.” Steel’s simple machine used a roller pitted with either small depressions or small raised pyramids to break fibers in the stamp paper. The rollers with depressions created a “points up” pattern while those with raised pyramids made a “points down” pattern.

The United States was the first country to issue grilled stamps and was the only country to do so until the mid-1870s, when Peru also began using grills. The National Bank Note Company was responsible for producing both countries’ stamps.

Grills were used for only nine years – 1867 to 1875, encompassing the 1869 Pictorial Series (#112-22) and the 1870-71 Bank Notes (#134-44). The National Bank Note Company attempted to find the perfect grill size by experimenting with various versions. The large A, B, and C grills weakened the paper too much. As time went on, the rollers were ground down to produce smaller-sized grills that would prevent the stamp from tearing easily, but wouldn’t let the ink penetrate the paper. That resulted in grills too weak to do the job. There was also the issue of extra expense, plus, the reuse of stamps wasn’t as prevalent as postal authorities feared. This historic postal era had come to an end.

In 1916, William L. Stevenson measured all known grill sizes and categorized them. He gave each a letter from A to J. The exception was the “Z” grill, as he was unsure to which grill family it belonged. Nor did he know which family it preceded or followed, so he used the letter “Z” to signify the unknown. It differs from other grill patterns because the tiny ridges on each peak are oriented horizontally instead of vertically.

Grills are classified by the dimensions of the grill pattern and are measured in millimeters or by counting the number of grill points. There are eleven major classifications.

“A” Grill Covers the entire stamp

“B” Grill 18x15mm (22x18pts)

“C” Grill 13x16mm (16-17x18-21pts)

“D” Grill 12x14mm (15-17-18pts)

“Z” Grill 11x14mm (14-15x17-18pts)

“E” Grill 11x13mm (14x15-17pts)

“F” Grill 9x13mm (11-12x15-17pts)

“G” Grill 9½ x9mm (12x11-11 ½ pts)

“H” Grill 10x12mm (11-13x14-16pts)

“I” Grill 8½ x10mm (10x11x10-13pts)

“J” Grill 7x9 ½ mm (10x12pts)

The letters classifying the various grill types do not denote the size, shape, or appearance of the grills. They indicate the order in which each was discovered.

Mostly visible from the back of the stamp only, grills may be felt by lightly running a fingertip over the surface. Depending on which roller was used, the pattern is “points up” or “points down.” The ridges on an indented roller force the paper into the recesses, creating raised points, while a roller with raised pyramids will cause the points to be forced down into the paper, forming a series of depressions.

Grilling resulted in some of the greatest U.S. stamp rarities, including the legendary 1c “Z” Grill (U.S. #85A) owned by Mystic Stamp Company for several years.

History the stamp represents: The “C” grill was rejected after a low quantity was issued, because it covered a large portion of the stamp and weakened it too much. This grill was the last of the “points up” grills.