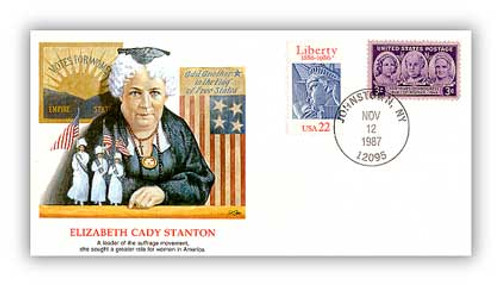

# 81873 - 1987 Eliz.Cady Stanton/Shapers of Am. Liberty

This limited-edition commemorative cover was produced to honor suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It features the Women's Progress stamp (that pictures Stanton) and was canceled on her 172nd birthday in her hometown of Johnstown, New York.

Birth of Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Suffragist and abolitionist Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born on November 12, 1815, in Johnstown, New York.

Stanton came from a prominent family and was the daughter of a lawyer and assemblyman. Her long talks with her father gave her a good informal knowledge of the laws of the day.

In 1840, Stanton married abolitionist lecturer Henry Stanton and often worked alongside him in the anti-slavery movement. While on their honeymoon in London in 1840, Stanton attempted to attend the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention. However, the male delegates at the convention voted that women weren’t allowed to participate in the proceedings. It was at this time that Stanton met Lucretia Mott, who was also upset to be barred from the convention’s proceedings. The women were eventually allowed to sit in a roped-off section out of view of the meeting. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison condemned the actions of the other men and chose to sit with the women in protest.

Stanton and Mott developed a close friendship and resolved that they would hold a women’s rights convention after they returned to the US. Eight years later they succeeded, holding the first Woman’s Right’s Convention in Seneca Falls on July 19, 1848. Over 300 people attended the convention and Stanton wrote and read a Declaration of Sentiments. Based on the Declaration of Independence, it declared men and women were created equal. Stanton also proposed the controversial resolution calling for voting rights for women. Thanks in part to an informal speech by Frederick Douglass in support of this, her resolution was among the many passed at that convention.

Stanton also listed 18 grievances such as women’s right to control their wages and property and the difficulties in gaining custody after a divorce. She urged social and legal changes to improve women’s place in society. Later that year she sent out petitions pushing the New York Congress to pass the New York Married Women’s Property Act.

Stanton met Susan B. Anthony in 1851 and worked closely with her on speeches, articles and books. Together they were the primary leaders of the women’s movement for more than 50 years. Stanton had seven children to raise, so she couldn’t always make it to events, but she would write speeches for Anthony to deliver.

During the Civil War, Stanton joined in the Union war efforts in New York City and helped push for the passage of the 13th Amendment that ended slavery. However, Stanton and Anthony opposed the 14th and 15th Amendments that would give voting rights to black men, because they didn’t give the same rights to women. This stance caused a rift with other suffragists and the two created the national Woman Suffrage Association in 1869. The two major suffragist groups would reunite in 1890.

However, by this time Stanton was 75 and didn’t travel and lecture as much. But she remained busy, writing three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, the Woman’s Bible, and her autobiography. Stanton died on October 26, 1902, in New York City, 18 years before women would gain the right to vote.

This limited-edition commemorative cover was produced to honor suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It features the Women's Progress stamp (that pictures Stanton) and was canceled on her 172nd birthday in her hometown of Johnstown, New York.

Birth of Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Suffragist and abolitionist Elizabeth Cady Stanton was born on November 12, 1815, in Johnstown, New York.

Stanton came from a prominent family and was the daughter of a lawyer and assemblyman. Her long talks with her father gave her a good informal knowledge of the laws of the day.

In 1840, Stanton married abolitionist lecturer Henry Stanton and often worked alongside him in the anti-slavery movement. While on their honeymoon in London in 1840, Stanton attempted to attend the World’s Anti-Slavery Convention. However, the male delegates at the convention voted that women weren’t allowed to participate in the proceedings. It was at this time that Stanton met Lucretia Mott, who was also upset to be barred from the convention’s proceedings. The women were eventually allowed to sit in a roped-off section out of view of the meeting. Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison condemned the actions of the other men and chose to sit with the women in protest.

Stanton and Mott developed a close friendship and resolved that they would hold a women’s rights convention after they returned to the US. Eight years later they succeeded, holding the first Woman’s Right’s Convention in Seneca Falls on July 19, 1848. Over 300 people attended the convention and Stanton wrote and read a Declaration of Sentiments. Based on the Declaration of Independence, it declared men and women were created equal. Stanton also proposed the controversial resolution calling for voting rights for women. Thanks in part to an informal speech by Frederick Douglass in support of this, her resolution was among the many passed at that convention.

Stanton also listed 18 grievances such as women’s right to control their wages and property and the difficulties in gaining custody after a divorce. She urged social and legal changes to improve women’s place in society. Later that year she sent out petitions pushing the New York Congress to pass the New York Married Women’s Property Act.

Stanton met Susan B. Anthony in 1851 and worked closely with her on speeches, articles and books. Together they were the primary leaders of the women’s movement for more than 50 years. Stanton had seven children to raise, so she couldn’t always make it to events, but she would write speeches for Anthony to deliver.

During the Civil War, Stanton joined in the Union war efforts in New York City and helped push for the passage of the 13th Amendment that ended slavery. However, Stanton and Anthony opposed the 14th and 15th Amendments that would give voting rights to black men, because they didn’t give the same rights to women. This stance caused a rift with other suffragists and the two created the national Woman Suffrage Association in 1869. The two major suffragist groups would reunite in 1890.

However, by this time Stanton was 75 and didn’t travel and lecture as much. But she remained busy, writing three volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage, the Woman’s Bible, and her autobiography. Stanton died on October 26, 1902, in New York City, 18 years before women would gain the right to vote.