# 766 - 1935 1c Restoration of Fort Dearborn

U.S. #766

1935 1¢ Restoration of Fort Dearborn

Issue Date: March 15, 1935

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 98,712

Battle Of Fort Dearborn

In a battle lasting only 15 minutes on August 15, 1812, the Potawatomi Indians attacked Fort Dearborn near present-day Chicago, Illinois, and burned it to the ground.

Fort Dearborn was built beside the Chicago River in 1803 and named after then-U.S. Secretary of War Henry Dearborn. That part of the country, the Northwest Territory, had been an area of contention for years. The United States first acquired it as part of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but clashes with local Native Americans continued over the years.

Two Shawnee brothers, the prophet Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh, sought to expel the “children of the Evil Spirit,” the American settler. They formed a confederation of several tribes and soon became allies with Britain.

As the war between the U.S. and Britain became apparent, violence increased in the area. After a band of Indians killed two white men nearby, many people from Chicago fled to Fort Dearborn for safety. There, 15 civilian men were organized into a militia.

When the British captured Fort Mackinac in July 1812, General William Hull sent orders to Captain Nathan Heald to evacuate Fort Dearborn, destroy the arms and ammunition, and give what was left to friendly Indians who could escort them to Fort Wayne. Heald was warned by a Potawatomi chief of an ambush, but the group decided to leave the fort anyway.

In response to this, Captain William Wells, the sub-Indian agent at Fort Wayne, organized a group of 30 Miami Indians to travel to Dearborn to escort the evacuees.

On August 14, Heald met with leaders of the Potawatomi to inform them that he was evacuating the fort. However, they misunderstood and thought he was offering to give them the fort’s firearms, ammunition, and money if they would escort the settlers to Fort Wayne.

Heald and Wells led the evacuation of the Fort on August 15. Their party consisted of 54 troops, 12 militia, nine women, and 12 children. About 1.5 miles from Dearborn, they encountered a band of Potawatomi warriors who quickly ambushed them. The cavalry made their way to a nearby dune to charge toward the attackers, leaving the wagon train of women and children. The militia stepped in and defended the wagons, but in the end, they were all killed.

In all, the battle lasted about 15 minutes. The surviving soldiers surrendered and were taken as prisoners. American losses included 26 soldiers, all 12 militiamen, two women, and 12 children, with the rest taken prisoner. The Indians then burned down the fort and no U.S. citizens entered the area until after the war. The confederacy’s victory was short-lived, as the U.S. accelerated its policy of Indian removal in response to the massacre.

Fort Dearborn was rebuilt in 1816 and a replica of it was created for the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago.

What are Farley’s Follies?

This story begins with the issue of the 1933 Newburgh Peace commemorative, Scott #727. U.S. Postmaster General James A. Farley removed several first-run sheets from the printing presses before they were gummed or perforated, and autographed them. He gave these stamps to President Franklin Roosevelt (an avid stamp collector), Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, the President’s secretary Louis Howe, various Post Office Department officials, and each of his children. Farley continued this practice with other new stamp issues.

These ungummed and imperforate stamps were not available to the public – Farley was creating precious philatelic rarities and distributing them to his boss and friends.

Needless to say, the philatelic community was outraged. However, when a New York City stamp dealer declared he had a sheet of 200 ungummed, imperforate Mother’s Day stamps signed by the postmaster general for sale, and that he had insured them for $20,000, the general public was upset as well. It was estimated that 160 of Farley’s special sheets had been distributed. That made a total value of $3,200,000!

A recall was suggested, but deemed impossible. Finally, the Post Office came up with a solution – the reissue, in sheet form, of all the stamps issued since March 4, 1933, in ungummed condition, imperforate and in sufficient numbers to satisfy public demand.

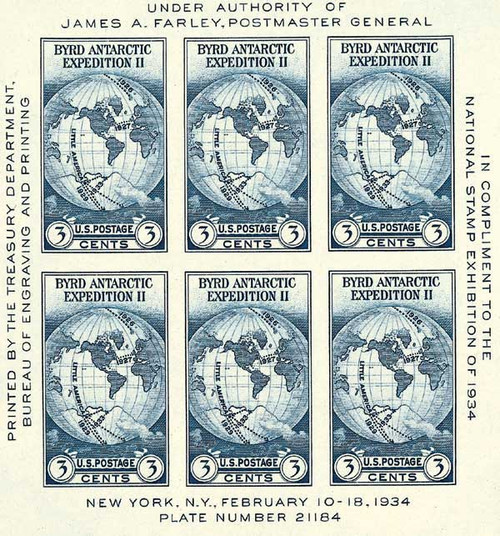

This imperforate, ungummed stamp comes from a souvenir sheet honoring Fort Dearborn, the original site of Chicago. It’s a reissue of the souvenir sheet issued for the 1933 American Philatelic Convention held in Chicago. Two of the main features on the Chicago Exposition grounds were meant to provide a contrast by which to measure the city’s progress. A restoration of Fort Dearborn, the original site of Chicago, which had twice been destroyed, stood in sight of the towering Federal Building, which dominated the grounds. These concrete symbols of Chicago’s progress were natural choices as stamp subjects.

Farley’s Follies are Scarce and Valuable Collectibles

The British stamp firm Gibbons reportedly declared the reprint was “nauseous prostitution,” and at first refused to list the issues in their famous stamp catalog! But even today, over 80 years after they were issued, collectors still love Farley’s Follies.

“Farley’s Follies” were issued in large sheets that are way too big to fit in stamp albums. So smart collectors snapped up blocks and pairs in a variety of formats instead. They not only fit, but these key formats are an easy way to understand the stamp printing process.

Mystic purchased full sheets of these mint stamps and made them available in scarce formats like vertical, horizontal and gutter pairs plus arrow blocks, line pairs and cross gutter blocks. All are hard to find – some occur only once in every stamp sheet. It’s a neat way to own a scandalous slice of US postal history..

U.S. #766

1935 1¢ Restoration of Fort Dearborn

Issue Date: March 15, 1935

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 98,712

Battle Of Fort Dearborn

In a battle lasting only 15 minutes on August 15, 1812, the Potawatomi Indians attacked Fort Dearborn near present-day Chicago, Illinois, and burned it to the ground.

Fort Dearborn was built beside the Chicago River in 1803 and named after then-U.S. Secretary of War Henry Dearborn. That part of the country, the Northwest Territory, had been an area of contention for years. The United States first acquired it as part of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, but clashes with local Native Americans continued over the years.

Two Shawnee brothers, the prophet Tenskwatawa and Tecumseh, sought to expel the “children of the Evil Spirit,” the American settler. They formed a confederation of several tribes and soon became allies with Britain.

As the war between the U.S. and Britain became apparent, violence increased in the area. After a band of Indians killed two white men nearby, many people from Chicago fled to Fort Dearborn for safety. There, 15 civilian men were organized into a militia.

When the British captured Fort Mackinac in July 1812, General William Hull sent orders to Captain Nathan Heald to evacuate Fort Dearborn, destroy the arms and ammunition, and give what was left to friendly Indians who could escort them to Fort Wayne. Heald was warned by a Potawatomi chief of an ambush, but the group decided to leave the fort anyway.

In response to this, Captain William Wells, the sub-Indian agent at Fort Wayne, organized a group of 30 Miami Indians to travel to Dearborn to escort the evacuees.

On August 14, Heald met with leaders of the Potawatomi to inform them that he was evacuating the fort. However, they misunderstood and thought he was offering to give them the fort’s firearms, ammunition, and money if they would escort the settlers to Fort Wayne.

Heald and Wells led the evacuation of the Fort on August 15. Their party consisted of 54 troops, 12 militia, nine women, and 12 children. About 1.5 miles from Dearborn, they encountered a band of Potawatomi warriors who quickly ambushed them. The cavalry made their way to a nearby dune to charge toward the attackers, leaving the wagon train of women and children. The militia stepped in and defended the wagons, but in the end, they were all killed.

In all, the battle lasted about 15 minutes. The surviving soldiers surrendered and were taken as prisoners. American losses included 26 soldiers, all 12 militiamen, two women, and 12 children, with the rest taken prisoner. The Indians then burned down the fort and no U.S. citizens entered the area until after the war. The confederacy’s victory was short-lived, as the U.S. accelerated its policy of Indian removal in response to the massacre.

Fort Dearborn was rebuilt in 1816 and a replica of it was created for the 1933 Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago.

What are Farley’s Follies?

This story begins with the issue of the 1933 Newburgh Peace commemorative, Scott #727. U.S. Postmaster General James A. Farley removed several first-run sheets from the printing presses before they were gummed or perforated, and autographed them. He gave these stamps to President Franklin Roosevelt (an avid stamp collector), Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, the President’s secretary Louis Howe, various Post Office Department officials, and each of his children. Farley continued this practice with other new stamp issues.

These ungummed and imperforate stamps were not available to the public – Farley was creating precious philatelic rarities and distributing them to his boss and friends.

Needless to say, the philatelic community was outraged. However, when a New York City stamp dealer declared he had a sheet of 200 ungummed, imperforate Mother’s Day stamps signed by the postmaster general for sale, and that he had insured them for $20,000, the general public was upset as well. It was estimated that 160 of Farley’s special sheets had been distributed. That made a total value of $3,200,000!

A recall was suggested, but deemed impossible. Finally, the Post Office came up with a solution – the reissue, in sheet form, of all the stamps issued since March 4, 1933, in ungummed condition, imperforate and in sufficient numbers to satisfy public demand.

This imperforate, ungummed stamp comes from a souvenir sheet honoring Fort Dearborn, the original site of Chicago. It’s a reissue of the souvenir sheet issued for the 1933 American Philatelic Convention held in Chicago. Two of the main features on the Chicago Exposition grounds were meant to provide a contrast by which to measure the city’s progress. A restoration of Fort Dearborn, the original site of Chicago, which had twice been destroyed, stood in sight of the towering Federal Building, which dominated the grounds. These concrete symbols of Chicago’s progress were natural choices as stamp subjects.

Farley’s Follies are Scarce and Valuable Collectibles

The British stamp firm Gibbons reportedly declared the reprint was “nauseous prostitution,” and at first refused to list the issues in their famous stamp catalog! But even today, over 80 years after they were issued, collectors still love Farley’s Follies.

“Farley’s Follies” were issued in large sheets that are way too big to fit in stamp albums. So smart collectors snapped up blocks and pairs in a variety of formats instead. They not only fit, but these key formats are an easy way to understand the stamp printing process.

Mystic purchased full sheets of these mint stamps and made them available in scarce formats like vertical, horizontal and gutter pairs plus arrow blocks, line pairs and cross gutter blocks. All are hard to find – some occur only once in every stamp sheet. It’s a neat way to own a scandalous slice of US postal history..