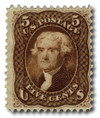

1863 5c Jefferson, Brown

# 76 - 1863 5c Jefferson, Brown

$24.00 - $825.00

U.S. #76

Series of 1861-66 5¢ Jefferson

Series of 1861-66 5¢ Jefferson

Earliest Known Use: February 3, 1863

Quantity issued: 6,500,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Brown

Quantity issued: 6,500,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Brown

Cyrus Durand, William D. Nichols, and William E. Marshall of the National Bank Note Company engraved James Macdonough’s design for the 1862 5¢ Jefferson issue.

Thomas Jefferson believed in the ability of people to govern themselves. Philosopher, inventor, diplomat, and statesman, he authored the Declaration of Independence, and was elected the third President of the United States in 1801.

The Series of 1861-66

In 1861, the United States began printing paper notes to finance its Civil War operations. Since the back of the notes were printed in green, they were commonly referred to as “greenbacks.” At first, the notes were redeemable in coins, but as the war raged on, they became merely promises of the U.S. government to pay. Since the notes had no metal money behind them as security, people began to hoard their gold and silver coins.

By 1862, greenbacks were being used more frequently, as coins disappeared from circulation. Eventually, small change vanished completely, and greenbacks were the only currency being used. Since much of what people needed cost less than a dollar, they found themselves faced with an unusual dilemma: how to pay for things without using their precious coins. Soon people were buying a dollar’s worth of stamps and using them as change instead.

As stamps became an accepted form of currency, several new ideas developed. In 1862, John Gault patented the idea of encasing postage stamps in circular metal frames behind a transparent shield of mica. Stores and manufacturing companies such as Ayer’s Pills, Burnett’s Cooking Extracts, and Lord & Taylor began impressing their name and product on the back of the metal frame and began using them for advertising. Known as encased postage, this form of change was widely used during the war.

Another new development was the idea of postage currency, which was approved by Congress on July 17, 1862. As a substitute for small change, U.S. Treasurer Francis Spinner began affixing stamps, singly and in multiples, to Treasury Paper. Although this was not considered actual money, it made stamps negotiable as currency. Eventually, the Treasury began printing the stamp designs on the paper, rather than using the stamps themselves. Postage currency remained in use until 1876, when Congress authorized the minting of silver coins.

U.S. #76

Series of 1861-66 5¢ Jefferson

Series of 1861-66 5¢ Jefferson

Earliest Known Use: February 3, 1863

Quantity issued: 6,500,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Brown

Quantity issued: 6,500,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Brown

Cyrus Durand, William D. Nichols, and William E. Marshall of the National Bank Note Company engraved James Macdonough’s design for the 1862 5¢ Jefferson issue.

Thomas Jefferson believed in the ability of people to govern themselves. Philosopher, inventor, diplomat, and statesman, he authored the Declaration of Independence, and was elected the third President of the United States in 1801.

The Series of 1861-66

In 1861, the United States began printing paper notes to finance its Civil War operations. Since the back of the notes were printed in green, they were commonly referred to as “greenbacks.” At first, the notes were redeemable in coins, but as the war raged on, they became merely promises of the U.S. government to pay. Since the notes had no metal money behind them as security, people began to hoard their gold and silver coins.

By 1862, greenbacks were being used more frequently, as coins disappeared from circulation. Eventually, small change vanished completely, and greenbacks were the only currency being used. Since much of what people needed cost less than a dollar, they found themselves faced with an unusual dilemma: how to pay for things without using their precious coins. Soon people were buying a dollar’s worth of stamps and using them as change instead.

As stamps became an accepted form of currency, several new ideas developed. In 1862, John Gault patented the idea of encasing postage stamps in circular metal frames behind a transparent shield of mica. Stores and manufacturing companies such as Ayer’s Pills, Burnett’s Cooking Extracts, and Lord & Taylor began impressing their name and product on the back of the metal frame and began using them for advertising. Known as encased postage, this form of change was widely used during the war.

Another new development was the idea of postage currency, which was approved by Congress on July 17, 1862. As a substitute for small change, U.S. Treasurer Francis Spinner began affixing stamps, singly and in multiples, to Treasury Paper. Although this was not considered actual money, it made stamps negotiable as currency. Eventually, the Treasury began printing the stamp designs on the paper, rather than using the stamps themselves. Postage currency remained in use until 1876, when Congress authorized the minting of silver coins.