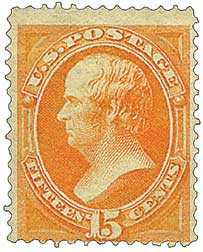

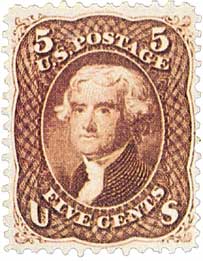

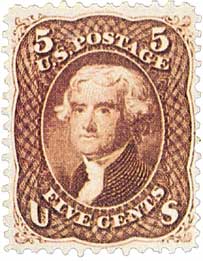

# 75 - 1861-66 5c Jefferson, red brown

Series of 1861-66 5¢ Jefferson

Quantity issued: 1,000,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Red brown

Department Of State Established

On July 27, 1789, the Department of Foreign Affairs was created, which was later renamed the Department of State.

When the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788, it specified that the President would be responsible for the country’s foreign relations. President George Washington soon realized he’d need help and requested the creation of a new executive department to help handle foreign affairs.

The House of Representatives and Senate agreed and approved legislation creating such a department on July 21, 1789. President Washington then signed the legislation on July 27, 1789, officially creating the Department of Foreign Affairs. It was the first department established under the U.S. Constitution. As the office’s responsibilities expanded to cover domestic duties as well as foreign, the agency’s name was changed to the Department of State.

The department was soon responsible for taking the census, managing the U.S. Mint, and keeping the Great Seal in addition to representing the country to other nations. Washington appointed the first Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, on September 29, 1789. Jefferson was serving as the minister to France at the time. John Jay, who had been secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation, continued in the post until Jefferson returned.

Jefferson returned to America and assumed his new duties in 1790. He supported France in its war with England, laid the foundation for the protection of American territory from Great Britain and Spain, established navigational rights on the Mississippi River, and created commerce treaties with Spain and England.

Over time, many of the Secretary of State’s domestic responsibilities were turned over to other departments as they were developed, though the secretary of state is still the keeper of the Great Seal. Another duty the secretary has is receiving the written document if a President or Vice President decides to resign.

The primary role of the department is to help the President develop and carry out a foreign policy. It employs about 5,000 people and has diplomats in more than 250 locations around the world. The State Department also serves foreigners trying to visit or immigrate to the U.S. and citizens who are living or traveling abroad. It’s involved in aid programs, fighting international crime, and training foreign militaries as well. The agency also promotes our businesses abroad, opening up new markets. This department issues passports and travel warnings as well.

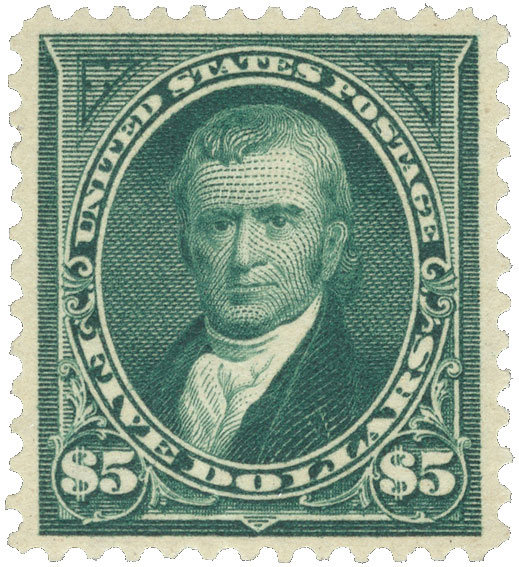

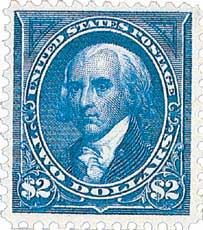

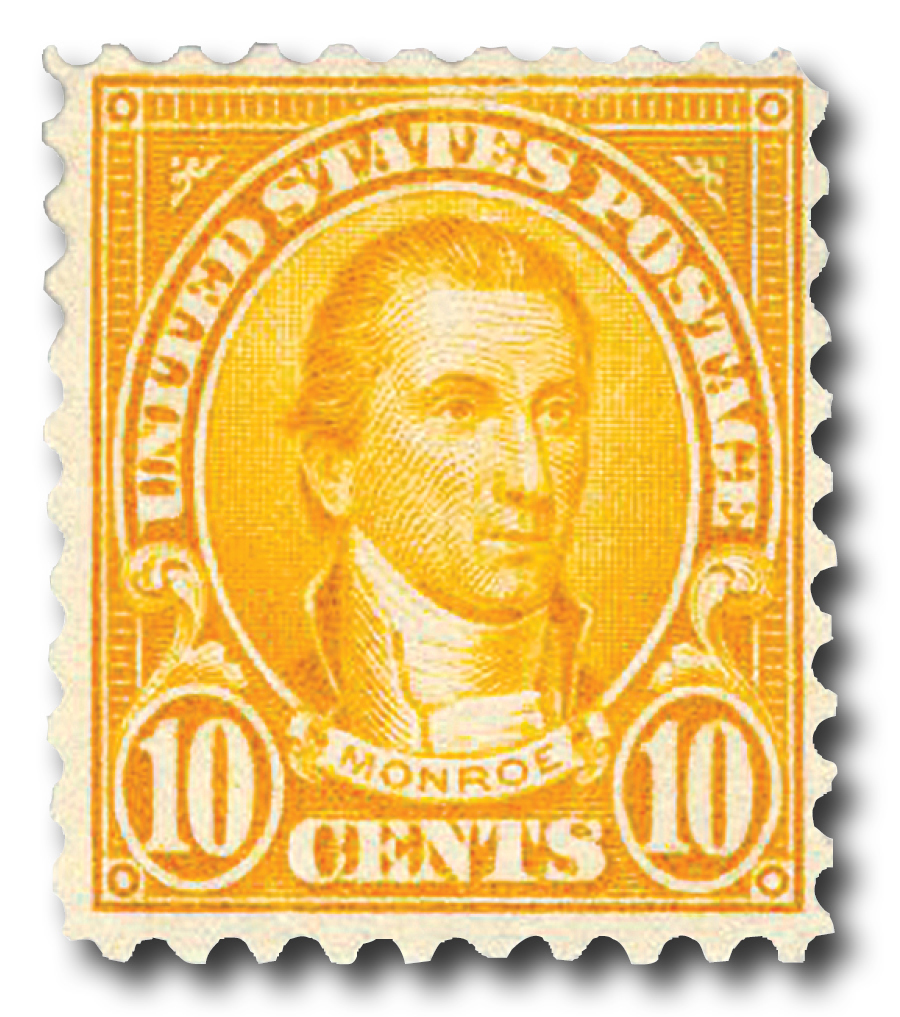

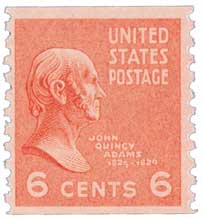

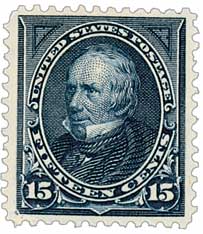

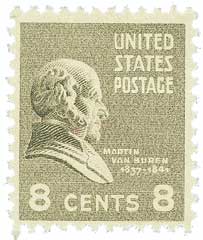

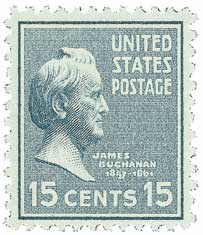

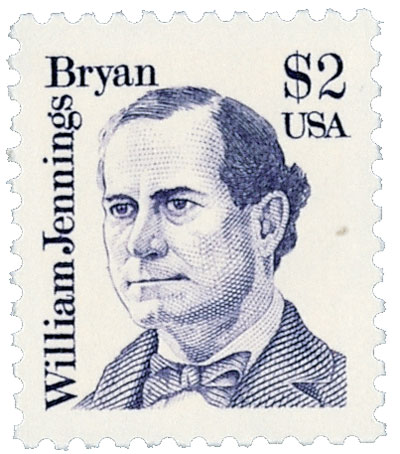

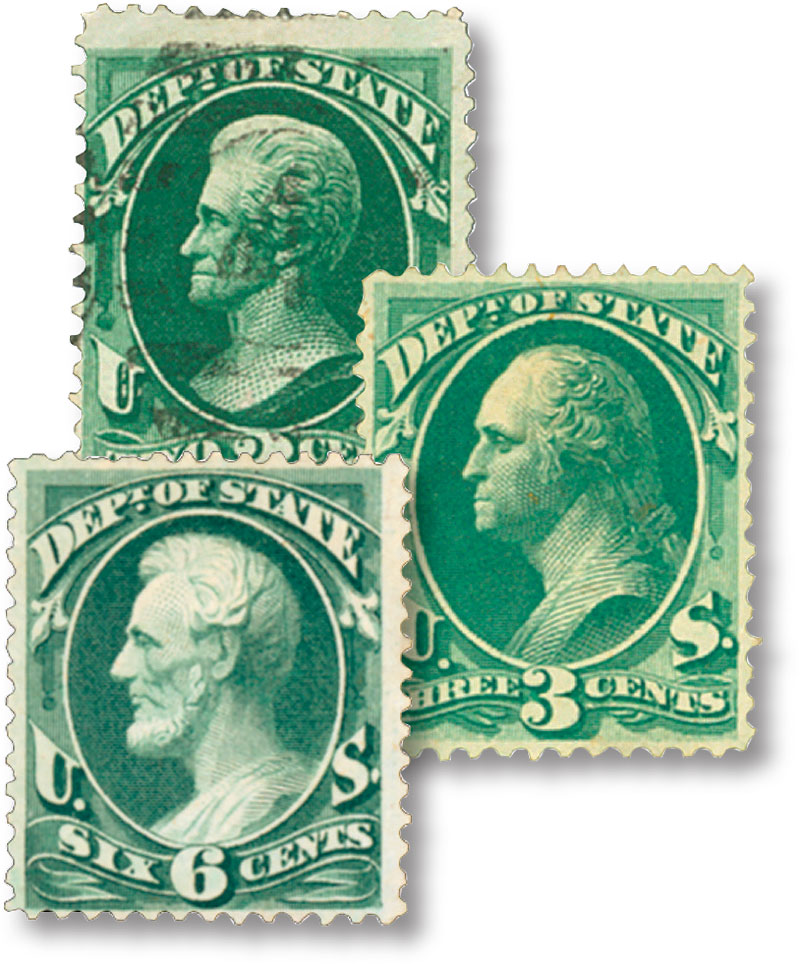

Many U.S. Secretaries of State have been honored on postage, including:

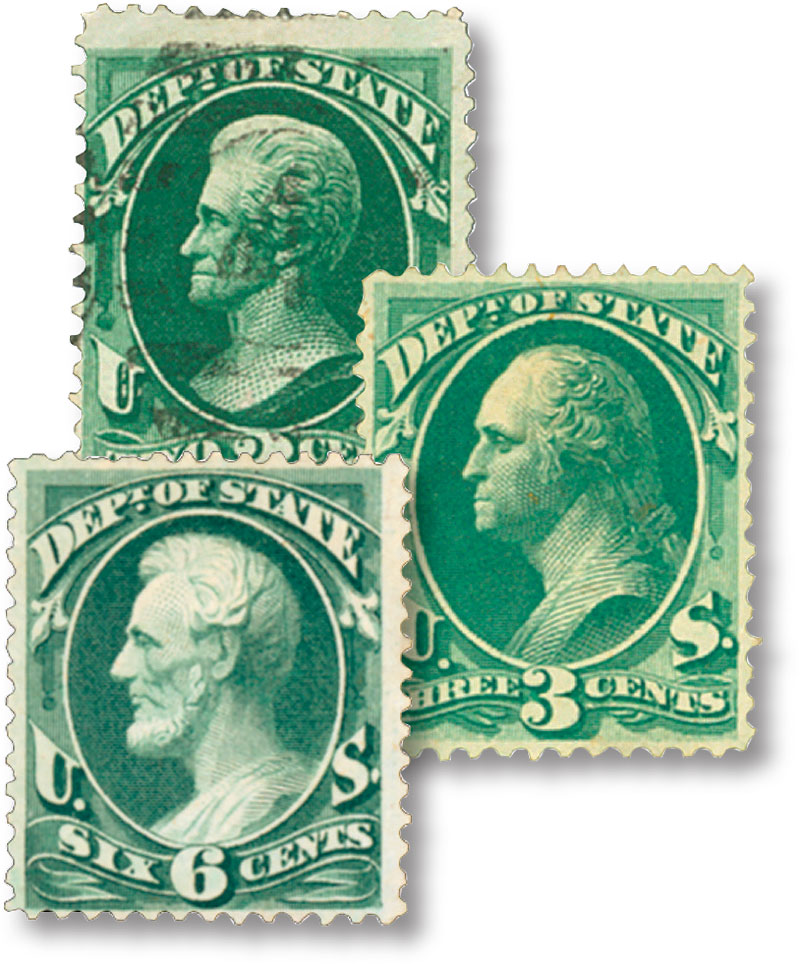

Official Mail

Official Mail stamps are genuine postage stamps, although they were never available at any post office. These unique stamps are called Officials because their use was strictly limited to government mail. Before 1873, government agencies had “franking” privileges. This meant that government mail could be sent free of postage as long as it bore an authorized signature on the envelope. As of July 1, 1873, “franking” privileges were discontinued and special official stamps were put into circulation for use on government mail.

Series of 1861-66 5¢ Jefferson

Quantity issued: 1,000,000 (estimate)

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Red brown

Department Of State Established

On July 27, 1789, the Department of Foreign Affairs was created, which was later renamed the Department of State.

When the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1788, it specified that the President would be responsible for the country’s foreign relations. President George Washington soon realized he’d need help and requested the creation of a new executive department to help handle foreign affairs.

The House of Representatives and Senate agreed and approved legislation creating such a department on July 21, 1789. President Washington then signed the legislation on July 27, 1789, officially creating the Department of Foreign Affairs. It was the first department established under the U.S. Constitution. As the office’s responsibilities expanded to cover domestic duties as well as foreign, the agency’s name was changed to the Department of State.

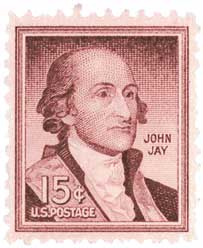

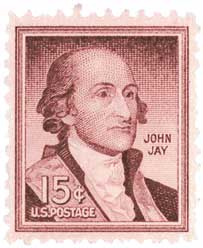

The department was soon responsible for taking the census, managing the U.S. Mint, and keeping the Great Seal in addition to representing the country to other nations. Washington appointed the first Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, on September 29, 1789. Jefferson was serving as the minister to France at the time. John Jay, who had been secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation, continued in the post until Jefferson returned.

Jefferson returned to America and assumed his new duties in 1790. He supported France in its war with England, laid the foundation for the protection of American territory from Great Britain and Spain, established navigational rights on the Mississippi River, and created commerce treaties with Spain and England.

Over time, many of the Secretary of State’s domestic responsibilities were turned over to other departments as they were developed, though the secretary of state is still the keeper of the Great Seal. Another duty the secretary has is receiving the written document if a President or Vice President decides to resign.

The primary role of the department is to help the President develop and carry out a foreign policy. It employs about 5,000 people and has diplomats in more than 250 locations around the world. The State Department also serves foreigners trying to visit or immigrate to the U.S. and citizens who are living or traveling abroad. It’s involved in aid programs, fighting international crime, and training foreign militaries as well. The agency also promotes our businesses abroad, opening up new markets. This department issues passports and travel warnings as well.

Many U.S. Secretaries of State have been honored on postage, including:

Official Mail

Official Mail stamps are genuine postage stamps, although they were never available at any post office. These unique stamps are called Officials because their use was strictly limited to government mail. Before 1873, government agencies had “franking” privileges. This meant that government mail could be sent free of postage as long as it bore an authorized signature on the envelope. As of July 1, 1873, “franking” privileges were discontinued and special official stamps were put into circulation for use on government mail.