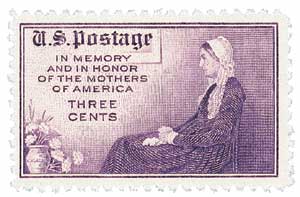

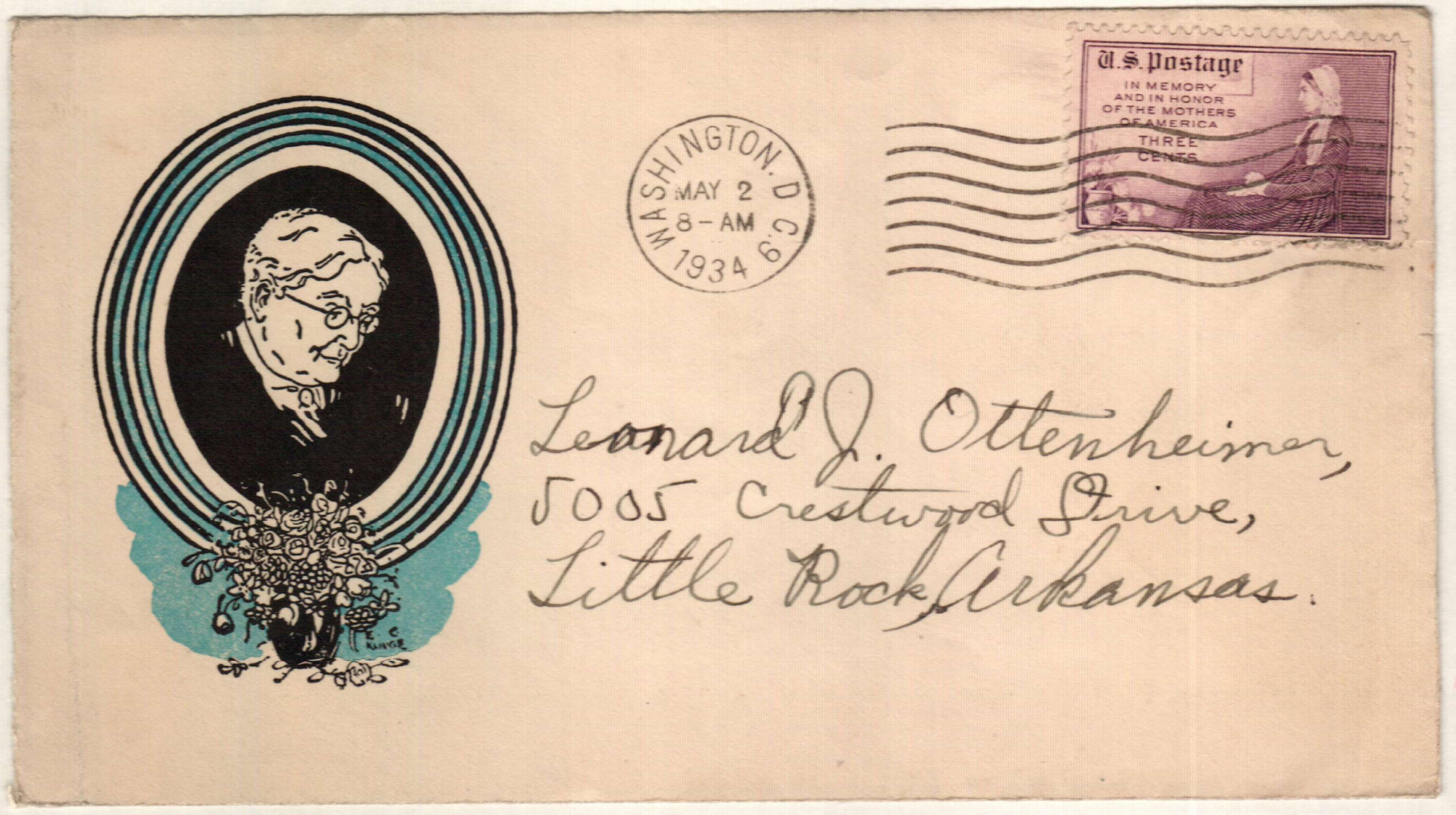

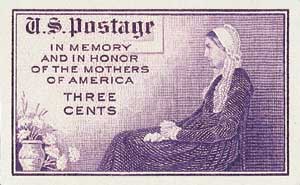

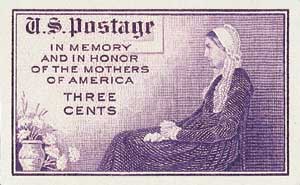

# 738 - 1934 3c Mothers of America, Flat Plate

1934 3¢ Mothers of America

Flat Plate Printing

Issue Date: May 2, 1934

Quantity Issued: 15,432,100

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat Plate Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Deep violet

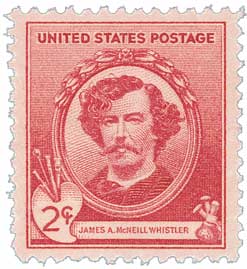

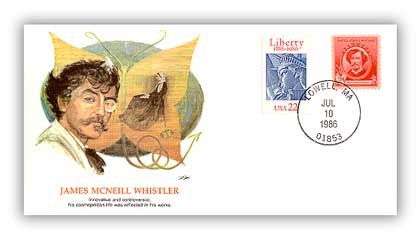

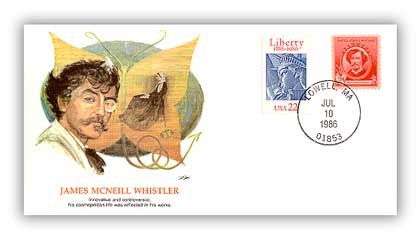

Happy Birthday James A. Whistler

Whistler’s family briefly moved to Stonington, Connecticut, and later Springfield, Massachusetts, where his father found success as chief engineer for the Boston and Albany Railroad. Soon, word of his father’s engineering ingenuity spread all the way to Russia. In 1842, Tsar Nicholas I offered Whistler’s father a position engineering a railroad from St. Petersburg to Moscow.

As a child, Whistler often displayed a poor temper and lack of focus. But his parents discovered that drawing helped him to focus and calm down. Realizing his budding talent, Whistler’s parents sent him to private art lessons and the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, where he earned top marks in anatomy. The Whistler family then spent some time in London, but following his father’s death, had to return to Connecticut.

While Whistler dreamed of becoming an artist, his mother sent him to school to become a minister. Realizing that would not suit him, Whistler applied to West Point. In his three years there Whistler earned poor grades and was known to defy authority and spout sarcastic quips. Superintendent Robert E. Lee eventually dismissed him.

Whistler was more resolved than ever to embark on an art career. With help from a wealthy friend he established a studio in Baltimore where he made important contacts before moving to Paris in 1855. He’d never return to America.

In Paris, Whistler studied at the Ecole Impériale. He sold few originals at first, but managed to make money by selling copies of paintings at the Louvre. In 1858, Whistler’s fortunes began to change as he met more artists that helped inspire him and mold his art theories. That year he exhibited his first work La Mere Gerard and moved to London the following year. In 1861 Whistler painted his first famous work, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, which raised both criticism and praise. People argued fiercely over the painting’s meaning, though Whistler saw it more as an arrangement of colors in harmony than a literal story.

In 1866 Whistler traveled to Chile, where he did his first nocturnal paintings. When he returned to London he continued to paint these night scenes for another 10 years. In the 1870s, he began to rename many of his earlier paintings with musical terms such as nocturne, symphony, harmony, study, and arrangement, emphasizing the tonal qualities and playing down the narratives.

Whistler painted his most famous work in 1871, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, better known as Whistler’s Mother. According to his mother, a model failed to show up for a session, so he asked her to stand in. When standing proved too tiring, she sat in the now famous pose for dozens of separate sittings. At the time, the painting wasn’t well received. Most paintings at the time were more flamboyant and most criticized it as too simple and a failed experiment. It was initially rejected by the Royal Academy, which only accepted it after extensive lobbying, and hung it in an unfavorable location. While many criticized it, others saw it as a “perfect symbol of motherhood” that displayed “the dignified feeling of old ladyhood.” Whistler would display the painting in several exhibits throughout his life and even authorized reproductions that led to its extensive fame.

Whistler held his first solo show in 1874 after he grew tired of continued poor placement of his paintings at the Royal Academy. His show was noted for his decoration of the hall. As one reviewer noted, “The visitor is struck, on entering the gallery, with a curious sense of harmony and fitness pervading it, and is more interested, perhaps, in the general effect than in any one work.”

In 1876 and 77, Whistler painted Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, a masterpiece in decorative mural art. He lost himself in the unending joy of harmonizing a room around Frederick Leyland’s collection of Chinese artifacts.

By the late 1870s, Whistler’s popularity was declining and his finances were suffering. He moved to Venice and experienced a productive boom, creating over 50 etchings, 100 pastels, and other works in about 14 months. Whistler also influenced American artists in Venice that brought his teachings back to the U.S. A younger generation of British and American artists idolized him and called themselves “pupils of Whistler.”

Whistler published his first book, Ten O’clock Lecture in 1885, which shared his believe that art was for art’s sake and that an artist’s responsibility was to himself and not society. He was then elected president of the Society of British Artists. In that role he presented Queen Victoria with an album containing his own writing and illustrations that she called “beautiful and artistic illumination.”

In the coming years Whistler experimented with color photography and lithography. His career reached its peak in 1890s, just as his wife was diagnosed with cancer. He continued to draw and paint from her hospital room and after her death. Whistler’s health declined in the coming years, resulting in his death on July 17, 1903.

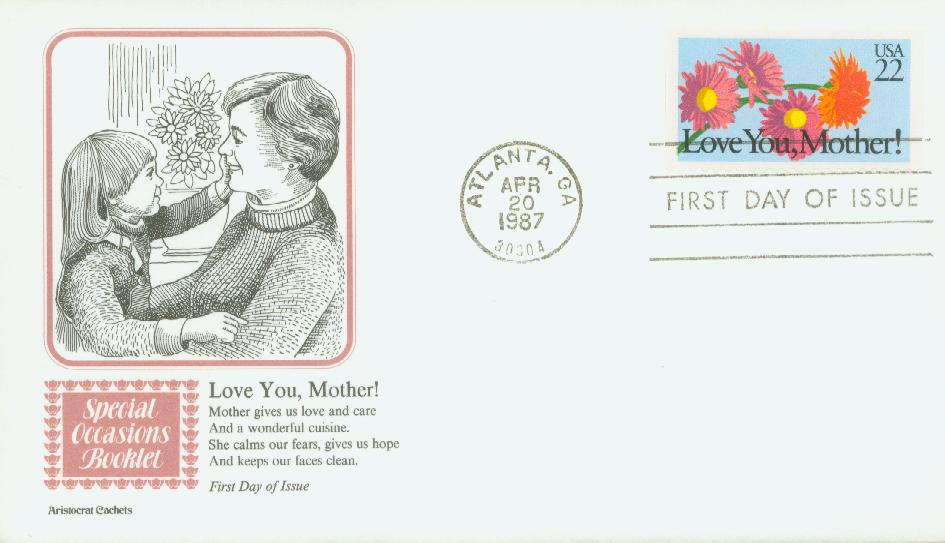

The First Mother’s Day

On May 10, 1908, the first official Mother’s Day celebration was held in Grafton, West Virginia.

In the 1800s, many women’s groups worked to create holidays to promote peace, including special meetings of mothers whose sons had fought or died on opposing sides of the Civil War. In 1868, Ann Jarvis formed a committee to create a Mother’s Friendship Day “to reunite families that had been divided during the Civil War.”

Previously, Jarvis had also created Mother’s Day Work Clubs to promote more sanitary conditions for Union and Confederate soldiers suffering from a typhoid outbreak. Jarvis hoped to create an annual holiday to celebrate mothers. In the late 1800s, there were lots of specialized celebrations, such as Children’s Day, Temperance Sunday, Roll Call Day, Decision Day, and Missionary Day. On June 2, 1872, Julia Ward Howe held a Mother’s Day for Peace anti-war demonstration and made an “appeal to womanhood throughout the world.” Howe led similar observances in Boston for about 10 years, but they eventually stopped.

Another early observance came on May 13, 1877, in Albion, Michigan. At the time, it was reported that three temperance advocates were forced at gunpoint to spend a night in a saloon and become drunk. After hearing of this, Juliet Calhoun Blakeley addressed the congregants of a local church and urged mothers to join her temperance cause. Her sons, who were traveling salesmen, were moved by their mother’s speech and promised to return home every year to honor her, as well as convince their business contacts to do the same. By the early 1880s, the Methodist Episcopal Church in Albion had set aside the second Sunday in May to honor mothers.

However, none of these celebrations caught on nationwide. Anna Jarvis, daughter of Ann Jarvis, is often credited as the founder of Mother’s Day. After her mother died in 1905, Anna became even more dedicated to establishing an official Mother’s Day observance. On May 12, 1907, she held a small service at Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton, West Virginia, where her mother had taught Sunday school. Then the following year she staged what’s recognized as the first official Mother’s Day, on May 10, 1908. The celebration included a church service as well as a larger ceremony at the Wanamaker Auditorium in Philadelphia. By the following year, Mother’s Day was being celebrated in New York.

From there, Jarvis wanted to make Mother’s Day a US holiday, and eventually an international holiday. In 1910, West Virginia declared it an official holiday, and other states quickly followed. Then in 1913, the House of Representatives called on the president and all federal officials to wear white carnations on May 11 to honor Mother’s Day.

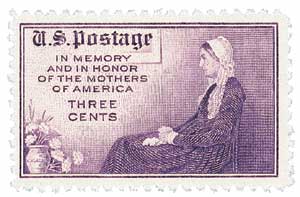

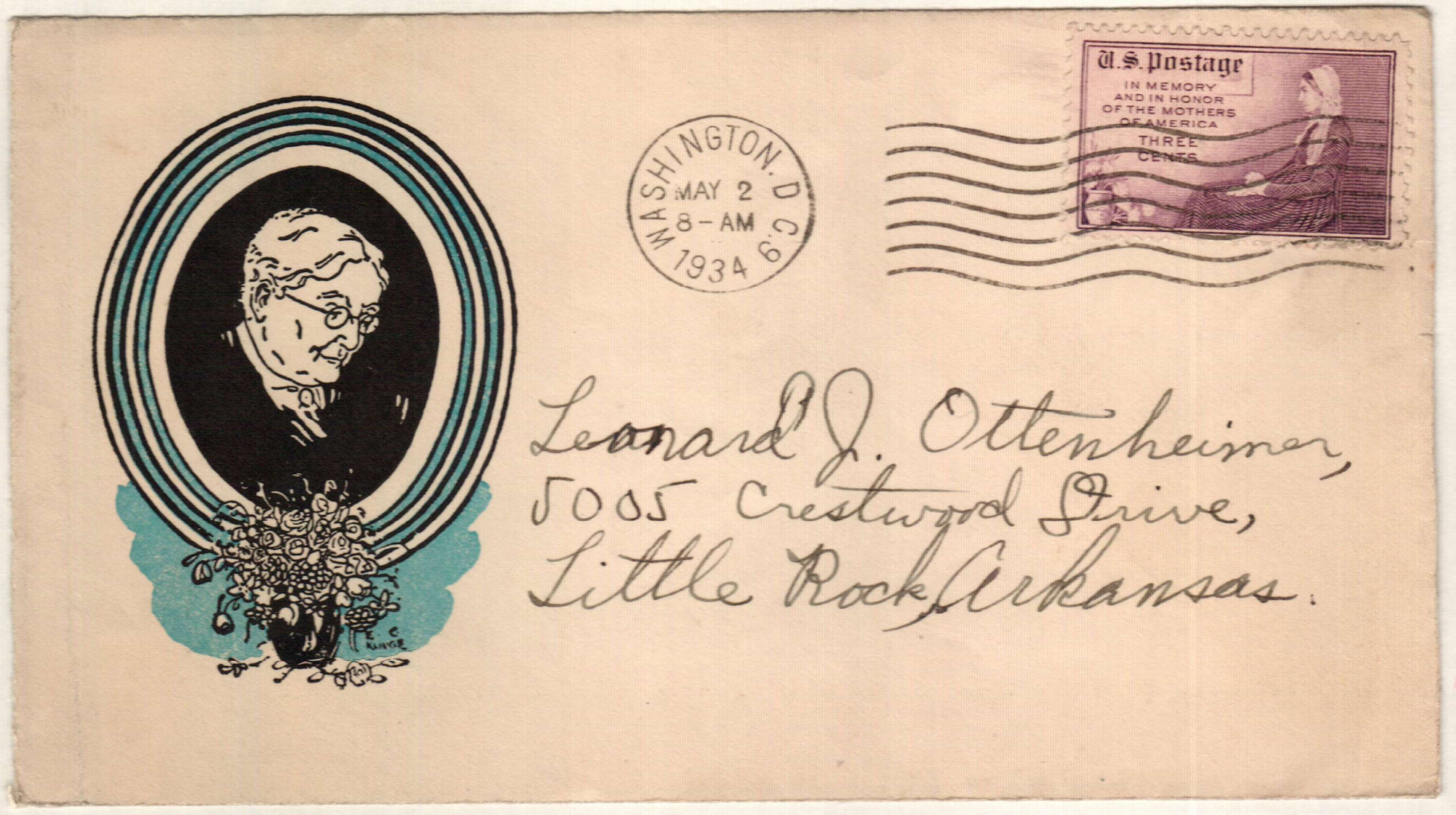

1934 3¢ Mothers of America

Flat Plate Printing

Issue Date: May 2, 1934

Quantity Issued: 15,432,100

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat Plate Press

Perforations: 11

Color: Deep violet

Happy Birthday James A. Whistler

Whistler’s family briefly moved to Stonington, Connecticut, and later Springfield, Massachusetts, where his father found success as chief engineer for the Boston and Albany Railroad. Soon, word of his father’s engineering ingenuity spread all the way to Russia. In 1842, Tsar Nicholas I offered Whistler’s father a position engineering a railroad from St. Petersburg to Moscow.

As a child, Whistler often displayed a poor temper and lack of focus. But his parents discovered that drawing helped him to focus and calm down. Realizing his budding talent, Whistler’s parents sent him to private art lessons and the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, where he earned top marks in anatomy. The Whistler family then spent some time in London, but following his father’s death, had to return to Connecticut.

While Whistler dreamed of becoming an artist, his mother sent him to school to become a minister. Realizing that would not suit him, Whistler applied to West Point. In his three years there Whistler earned poor grades and was known to defy authority and spout sarcastic quips. Superintendent Robert E. Lee eventually dismissed him.

Whistler was more resolved than ever to embark on an art career. With help from a wealthy friend he established a studio in Baltimore where he made important contacts before moving to Paris in 1855. He’d never return to America.

In Paris, Whistler studied at the Ecole Impériale. He sold few originals at first, but managed to make money by selling copies of paintings at the Louvre. In 1858, Whistler’s fortunes began to change as he met more artists that helped inspire him and mold his art theories. That year he exhibited his first work La Mere Gerard and moved to London the following year. In 1861 Whistler painted his first famous work, Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl, which raised both criticism and praise. People argued fiercely over the painting’s meaning, though Whistler saw it more as an arrangement of colors in harmony than a literal story.

In 1866 Whistler traveled to Chile, where he did his first nocturnal paintings. When he returned to London he continued to paint these night scenes for another 10 years. In the 1870s, he began to rename many of his earlier paintings with musical terms such as nocturne, symphony, harmony, study, and arrangement, emphasizing the tonal qualities and playing down the narratives.

Whistler painted his most famous work in 1871, Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, better known as Whistler’s Mother. According to his mother, a model failed to show up for a session, so he asked her to stand in. When standing proved too tiring, she sat in the now famous pose for dozens of separate sittings. At the time, the painting wasn’t well received. Most paintings at the time were more flamboyant and most criticized it as too simple and a failed experiment. It was initially rejected by the Royal Academy, which only accepted it after extensive lobbying, and hung it in an unfavorable location. While many criticized it, others saw it as a “perfect symbol of motherhood” that displayed “the dignified feeling of old ladyhood.” Whistler would display the painting in several exhibits throughout his life and even authorized reproductions that led to its extensive fame.

Whistler held his first solo show in 1874 after he grew tired of continued poor placement of his paintings at the Royal Academy. His show was noted for his decoration of the hall. As one reviewer noted, “The visitor is struck, on entering the gallery, with a curious sense of harmony and fitness pervading it, and is more interested, perhaps, in the general effect than in any one work.”

In 1876 and 77, Whistler painted Harmony in Blue and Gold: The Peacock Room, a masterpiece in decorative mural art. He lost himself in the unending joy of harmonizing a room around Frederick Leyland’s collection of Chinese artifacts.

By the late 1870s, Whistler’s popularity was declining and his finances were suffering. He moved to Venice and experienced a productive boom, creating over 50 etchings, 100 pastels, and other works in about 14 months. Whistler also influenced American artists in Venice that brought his teachings back to the U.S. A younger generation of British and American artists idolized him and called themselves “pupils of Whistler.”

Whistler published his first book, Ten O’clock Lecture in 1885, which shared his believe that art was for art’s sake and that an artist’s responsibility was to himself and not society. He was then elected president of the Society of British Artists. In that role he presented Queen Victoria with an album containing his own writing and illustrations that she called “beautiful and artistic illumination.”

In the coming years Whistler experimented with color photography and lithography. His career reached its peak in 1890s, just as his wife was diagnosed with cancer. He continued to draw and paint from her hospital room and after her death. Whistler’s health declined in the coming years, resulting in his death on July 17, 1903.

The First Mother’s Day

On May 10, 1908, the first official Mother’s Day celebration was held in Grafton, West Virginia.

In the 1800s, many women’s groups worked to create holidays to promote peace, including special meetings of mothers whose sons had fought or died on opposing sides of the Civil War. In 1868, Ann Jarvis formed a committee to create a Mother’s Friendship Day “to reunite families that had been divided during the Civil War.”

Previously, Jarvis had also created Mother’s Day Work Clubs to promote more sanitary conditions for Union and Confederate soldiers suffering from a typhoid outbreak. Jarvis hoped to create an annual holiday to celebrate mothers. In the late 1800s, there were lots of specialized celebrations, such as Children’s Day, Temperance Sunday, Roll Call Day, Decision Day, and Missionary Day. On June 2, 1872, Julia Ward Howe held a Mother’s Day for Peace anti-war demonstration and made an “appeal to womanhood throughout the world.” Howe led similar observances in Boston for about 10 years, but they eventually stopped.

Another early observance came on May 13, 1877, in Albion, Michigan. At the time, it was reported that three temperance advocates were forced at gunpoint to spend a night in a saloon and become drunk. After hearing of this, Juliet Calhoun Blakeley addressed the congregants of a local church and urged mothers to join her temperance cause. Her sons, who were traveling salesmen, were moved by their mother’s speech and promised to return home every year to honor her, as well as convince their business contacts to do the same. By the early 1880s, the Methodist Episcopal Church in Albion had set aside the second Sunday in May to honor mothers.

However, none of these celebrations caught on nationwide. Anna Jarvis, daughter of Ann Jarvis, is often credited as the founder of Mother’s Day. After her mother died in 1905, Anna became even more dedicated to establishing an official Mother’s Day observance. On May 12, 1907, she held a small service at Andrew’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Grafton, West Virginia, where her mother had taught Sunday school. Then the following year she staged what’s recognized as the first official Mother’s Day, on May 10, 1908. The celebration included a church service as well as a larger ceremony at the Wanamaker Auditorium in Philadelphia. By the following year, Mother’s Day was being celebrated in New York.

From there, Jarvis wanted to make Mother’s Day a US holiday, and eventually an international holiday. In 1910, West Virginia declared it an official holiday, and other states quickly followed. Then in 1913, the House of Representatives called on the president and all federal officials to wear white carnations on May 11 to honor Mother’s Day.