# 551 - 1925 1/2c Nathan Hale, olive brown

Series of 1922-25 1/2¢ Nathan Hale

Flat Plate Printing

First City: New Haven, CT and Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 626,241,783

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat plate

Perforation: 11 gauge

Color: Olive brown

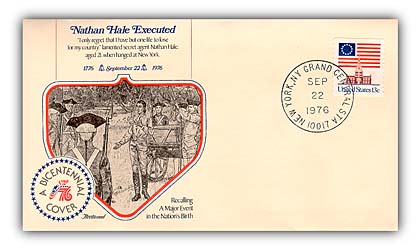

Hanging Of Patriot Nathan Hale

After being discovered as an American spy behind enemy lines, Nathan Hale was hanged on September 22, 1776.

Born in Coventry, Connecticut, Nathan Hale attended Yale College where he belonged to the Linonian Society, which debated astronomy, mathematics, literature, and slavery. He graduated with first class honors at the age of 18 in 1773.

Hale served as a teacher for a few years but when the Revolutionary War broke out, he joined the Connecticut militia. Within five months, he received a lieutenant's commission from the Connecticut Assembly, and took part in the siege of Boston.

When the British left Boston and entered the New York area, Hale was among the patriots that went to continue fighting there. Hale's bravery and leadership had already earned him the rank of captain in the Continental Army. His leadership in the capture of a British supply vessel guarded by a warship won him a place in the Rangers. This elite fighting group was used for the most dangerous and crucial missions.

Preparing for the Battle of Long Island, General George Washington asked the Rangers commander to select a man for a surveillance mission. Before he could pick anyone, Hale volunteered.

Disguised as a Dutch schoolmaster, Hale managed to pass through enemy lines. While on his mission, New York City fell to the British on September 15, 1776, and Washington and his forces retreated. Then, on September 21, the Great New York Fire destroyed much of the lower portion of Manhattan. In the wake of the fire, the British rounded up 200 Americans to find out who was to blame.

There are conflicting accounts as to how Hale was discovered. One story claims Major Robert Rogers of the Queen's Rangers recognized Hale and posed as a patriot to get Hale out himself as an American spy. According to other sources, it was his own loyalist cousin, Samuel Hale, who turned him over to the British.

British General William Howe personally questioned Hale. And when he found documents supporting the claim Hale was an American spy, he was condemned to hang. He spent the night before his hanging in a greenhouse and requested a bible and a clergyman. Both of his requests were denied.

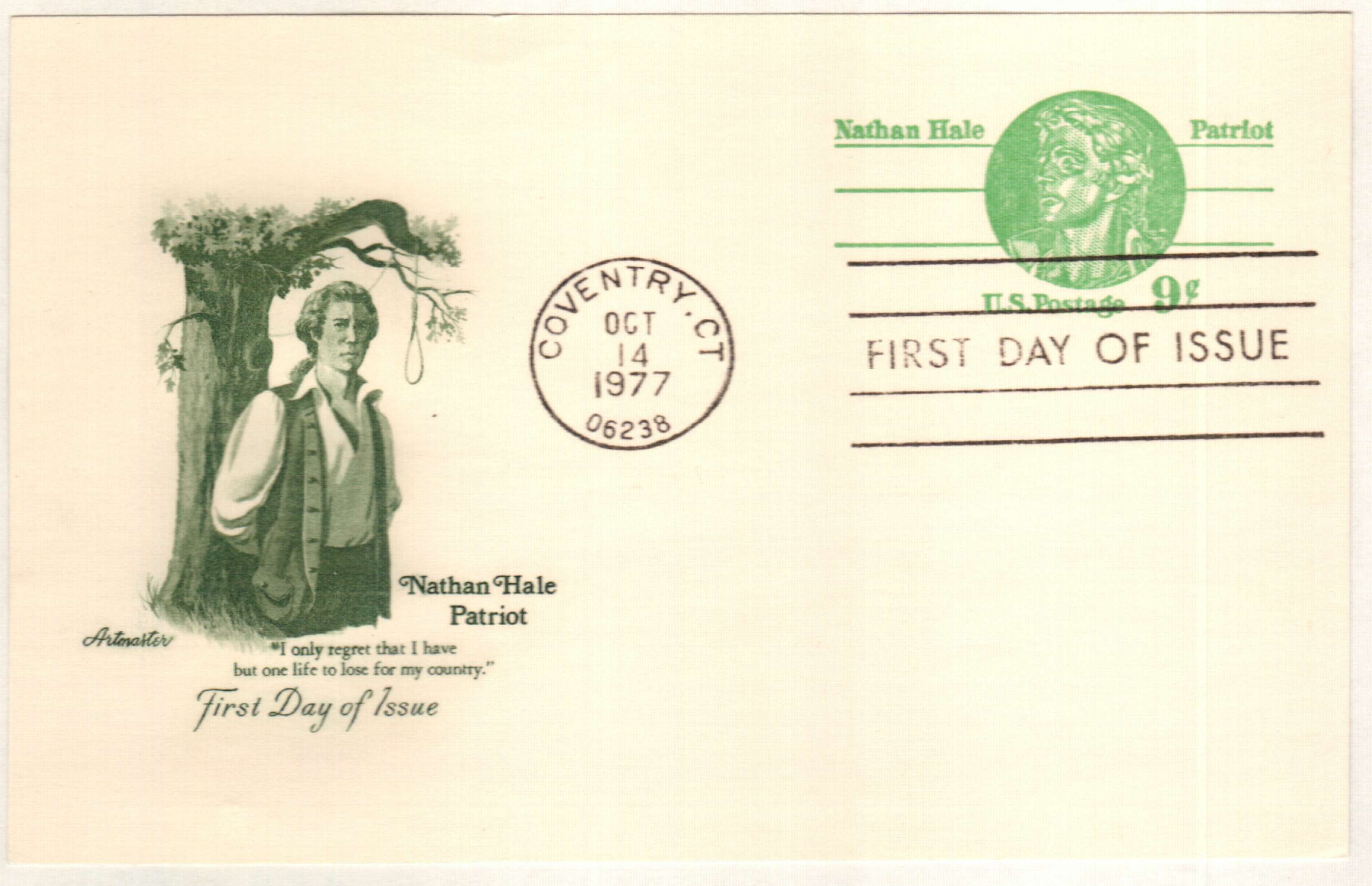

Hale, 21 years old at the time, was remarkably calm before his execution. Multiple reports say that he made a final speech before his hanging, claiming, "I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country." Stories of Hale's patriotic speech were relayed from British officers to American officers, who shared it with the public, making Hale a national hero.

There has been some question over the years regarding Hale's final words. It's been suggested his speech may have included a line from the play Cato, which states, "How beautiful is death, when earn'd by virtue! Who would not be that youth? What pity is it that we can die but once to serve our country."

Whether the words were his own, or taken from the play, even the British officers that witnessed his final moments admitted Hale exhibited bravery and composure, making him a true American hero.

The Series of 1922-25 and the Wheels of Progress

In 1847, when the printing presses first began to move, they didn't roll - they "stamped" in a process known as flat plate printing. The Regular Series of 1922 was the last to be printed by flat plate press, after which stamps were produced by rotary press printing.

By 1926, all denominations up to 10¢ - except the new ½¢ - were printed by rotary press. For a while, $1 to $5 issues were done on flat plate press due to smaller demand.

In 1922, the Post Office Department announced its decision to issue a new series of stamps to replace the Washington-Franklin series, which had been in use since 1908. Many criticized the change, believing it was being made to satisfy collectors rather than to fill an actual need. However, the similar designs and colors of the current stamps caused confusion, resulting in a substantial loss in revenue each year. In busy situations, postal clerks could not tell at a glance if the correct postage was being used.

Postal employees requested a variety of designs which could easily be distinguished from one another. Great care was taken to make sure the new designs could not be confused. Although the frames are similar, the vignettes (central designs) are distinctive. Prominent Americans, as well as scenes of national interest, were chosen as subjects for the new series.

In addition to issuing new designs, the Department developed a plan to first distribute a small number of each stamp on a particular date in a selected town which was of historical and geographical significance to the subject. The plan greatly increased interest and began a new trend of collecting stamps on covers or envelopes postmarked on the first day of issue.

Series of 1922-25 1/2¢ Nathan Hale

Flat Plate Printing

First City: New Haven, CT and Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 626,241,783

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat plate

Perforation: 11 gauge

Color: Olive brown

Hanging Of Patriot Nathan Hale

After being discovered as an American spy behind enemy lines, Nathan Hale was hanged on September 22, 1776.

Born in Coventry, Connecticut, Nathan Hale attended Yale College where he belonged to the Linonian Society, which debated astronomy, mathematics, literature, and slavery. He graduated with first class honors at the age of 18 in 1773.

Hale served as a teacher for a few years but when the Revolutionary War broke out, he joined the Connecticut militia. Within five months, he received a lieutenant's commission from the Connecticut Assembly, and took part in the siege of Boston.

When the British left Boston and entered the New York area, Hale was among the patriots that went to continue fighting there. Hale's bravery and leadership had already earned him the rank of captain in the Continental Army. His leadership in the capture of a British supply vessel guarded by a warship won him a place in the Rangers. This elite fighting group was used for the most dangerous and crucial missions.

Preparing for the Battle of Long Island, General George Washington asked the Rangers commander to select a man for a surveillance mission. Before he could pick anyone, Hale volunteered.

Disguised as a Dutch schoolmaster, Hale managed to pass through enemy lines. While on his mission, New York City fell to the British on September 15, 1776, and Washington and his forces retreated. Then, on September 21, the Great New York Fire destroyed much of the lower portion of Manhattan. In the wake of the fire, the British rounded up 200 Americans to find out who was to blame.

There are conflicting accounts as to how Hale was discovered. One story claims Major Robert Rogers of the Queen's Rangers recognized Hale and posed as a patriot to get Hale out himself as an American spy. According to other sources, it was his own loyalist cousin, Samuel Hale, who turned him over to the British.

British General William Howe personally questioned Hale. And when he found documents supporting the claim Hale was an American spy, he was condemned to hang. He spent the night before his hanging in a greenhouse and requested a bible and a clergyman. Both of his requests were denied.

Hale, 21 years old at the time, was remarkably calm before his execution. Multiple reports say that he made a final speech before his hanging, claiming, "I only regret that I have but one life to lose for my country." Stories of Hale's patriotic speech were relayed from British officers to American officers, who shared it with the public, making Hale a national hero.

There has been some question over the years regarding Hale's final words. It's been suggested his speech may have included a line from the play Cato, which states, "How beautiful is death, when earn'd by virtue! Who would not be that youth? What pity is it that we can die but once to serve our country."

Whether the words were his own, or taken from the play, even the British officers that witnessed his final moments admitted Hale exhibited bravery and composure, making him a true American hero.

The Series of 1922-25 and the Wheels of Progress

In 1847, when the printing presses first began to move, they didn't roll - they "stamped" in a process known as flat plate printing. The Regular Series of 1922 was the last to be printed by flat plate press, after which stamps were produced by rotary press printing.

By 1926, all denominations up to 10¢ - except the new ½¢ - were printed by rotary press. For a while, $1 to $5 issues were done on flat plate press due to smaller demand.

In 1922, the Post Office Department announced its decision to issue a new series of stamps to replace the Washington-Franklin series, which had been in use since 1908. Many criticized the change, believing it was being made to satisfy collectors rather than to fill an actual need. However, the similar designs and colors of the current stamps caused confusion, resulting in a substantial loss in revenue each year. In busy situations, postal clerks could not tell at a glance if the correct postage was being used.

Postal employees requested a variety of designs which could easily be distinguished from one another. Great care was taken to make sure the new designs could not be confused. Although the frames are similar, the vignettes (central designs) are distinctive. Prominent Americans, as well as scenes of national interest, were chosen as subjects for the new series.

In addition to issuing new designs, the Department developed a plan to first distribute a small number of each stamp on a particular date in a selected town which was of historical and geographical significance to the subject. The plan greatly increased interest and began a new trend of collecting stamps on covers or envelopes postmarked on the first day of issue.