# 5065-68 - 2016 First-Class Forever Stamp - Distinguished Service Cross Medals

General John J. Pershing, commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, felt the U.S. should have an honor for gallantry and risk-of-life in addition – and secondary to – the Medal of Honor. He proposed the idea to President Woodrow Wilson, and the Distinguished Service Cross was authorized in 1918. It was then awarded retroactively to 1917, and several even-older merit medals were upgraded.

Originally, the service cross was established to cover all people who acted on behalf of the U.S. military with extraordinary heroism in a combat situation. But over time, the other military branches created their own service cross medals. Today, second only to the Medal of Honor, there are now four service cross medals for the separate U.S. military branches: the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross, the Navy Cross, the Air Force Cross, and the Coast Guard Cross.

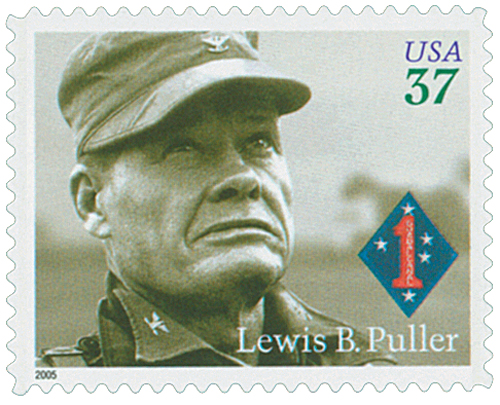

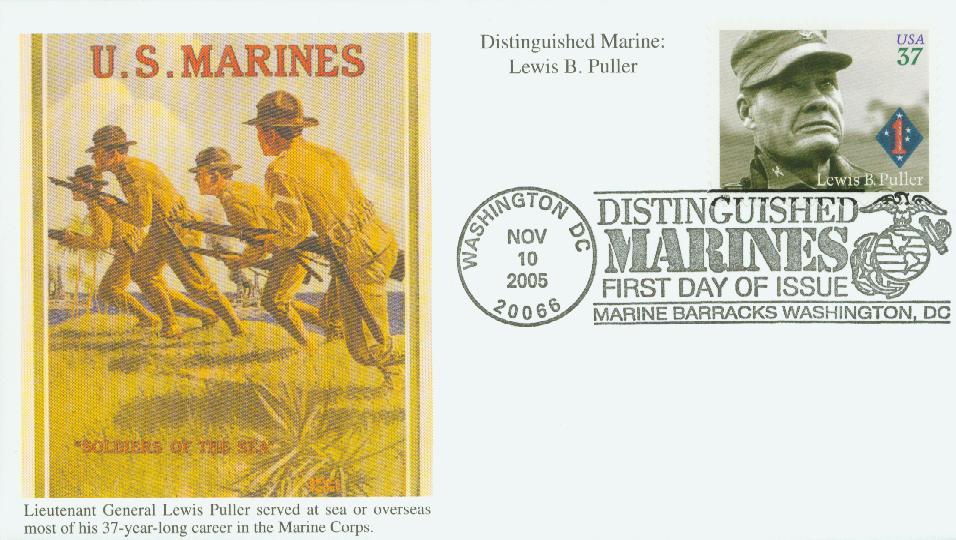

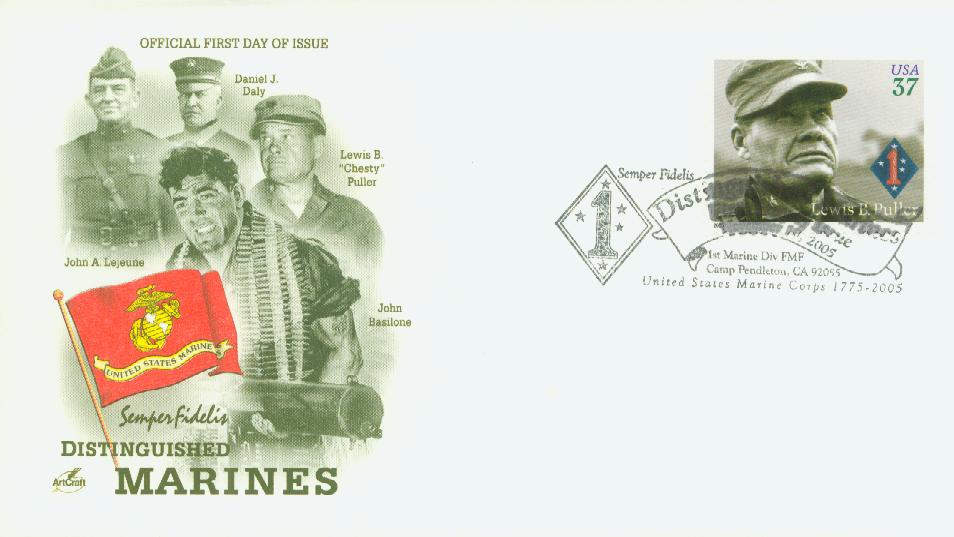

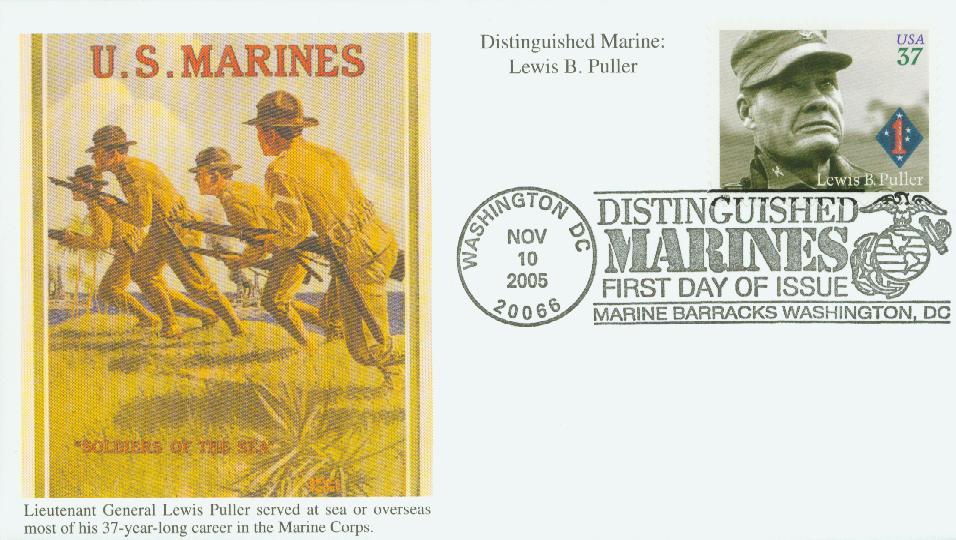

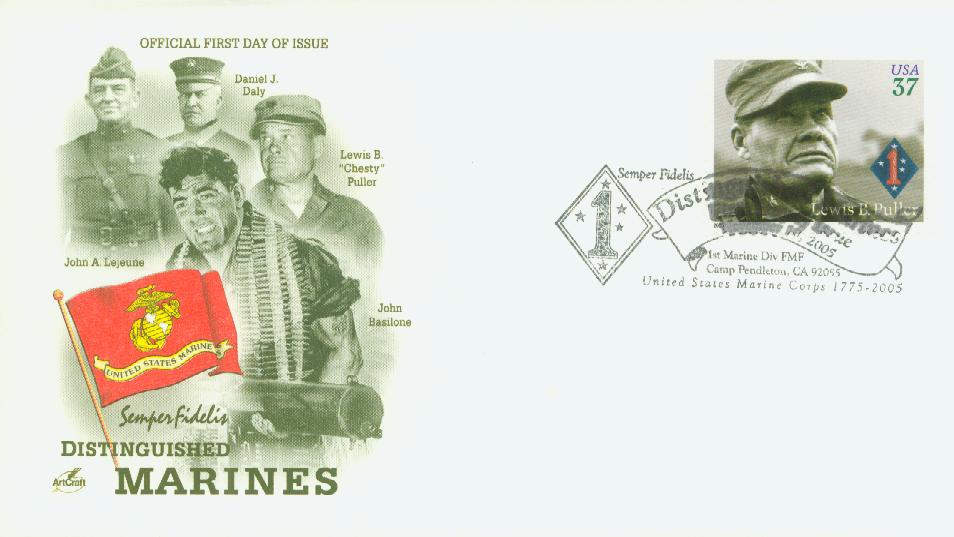

Birth Of Chesty Puller

As a child, Puller enjoyed listening to the tales of Civil War veterans and particularly idolized “Stonewall” Jackson. He had hoped to join in the Border War with Mexico in 1916, but he was too young and his mother wouldn’t consent to let him go.

Puller then went to the Virginia Military Institute in 1917, but left the following year to join in World War I. Hearing tales of the 5th Marines at Belleau Wood, he decided to join the Marines and “go where the guns are.” Puller never saw action in the war, but went on to attend the non-commissioned officer school and Officer Candidates School.

As American forces were reduced following the war, Puller was put on inactive status. He later received orders to go to Haiti, where he took part in more than 40 fights over five years against Caco rebels. Then in 1928, Puller was sent to Nicaragua for a similar mission. While there, he received two Navy Crosses. The first was for leading “five successive engagements against superior numbers of armed bandit forces.” The second was for leading Nicaraguan National Guardsmen in the final battle of the rebellion. After that conflict, Puller went to China twice to command Chinese and American Marines.

Just before World War II, Puller was placed in command of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. In 1942, they landed on Guadalcanal, where Puller earned his third Navy Cross. In one action alone, his Marines killed 1,400 hostile troops, held ground until reinforcements arrived, and suffered fewer than 70 casualties. He earned his fourth Navy Cross for action on Cape Gloucester, New Britain, in 1944. When the leaders of two battalions were wounded, he took over and moved through heavy fire to command their units.

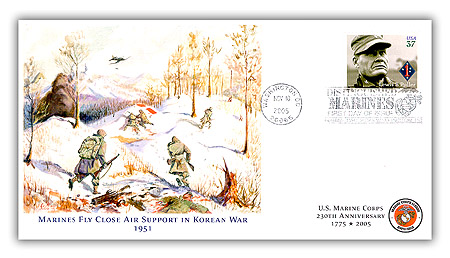

Puller returned to the US in November 1944 and held a series of leadership positions. Then in 1950, as America entered the Korean War, he was called upon once again to lead Marines into battle. Puller was over 50 years old when he took part in the September 1950 Battle of Inchon as commander of the 1st Marine Regiment. Puller led his men fearlessly as the UN forces, made up mostly of Americans, advanced north following the retreating North Korean People’s Army.

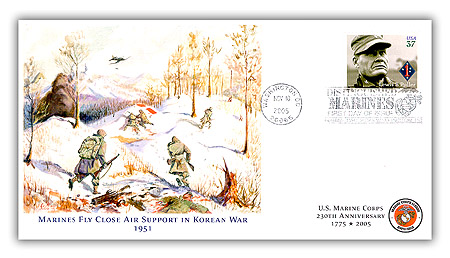

By December, they were near the Chosin Reservoir when China’s People’s Volunteer Army poured over the China-North Korea border and surrounded the UN army. When Puller was updated about the dire situation he said, “We’ve been looking for the enemy for some time now. We’ve finally found him. We’re surrounded. That simplifies things.” His Marines managed to keep supply lines open and acted as rear guard during withdrawal. They destroyed seven of the enemy’s 22 divisions and inflicted heavy casualties on the rest. Puller was awarded his fifth Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism during the operation, the most of any Marine in US history.

After completing his tour of duty in Korea, Puller trained Marines in California. He suffered a stroke and retired in 1955. He died on October 11, 1972. Puller was and still remains a popular figure and spirit de corps in the Marines. During boot camp, it’s common for Marines to say “Good night, Chesty, wherever you are!” They may also exclaim, “Chesty Puller never quit!” or tell each other while doing push-ups “do one for Chesty!” There’s also “It was good for Chesty Puller and it’s good enough for me” as well as “Tell Chesty Puller I did my best.”

General John J. Pershing, commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Forces in France, felt the U.S. should have an honor for gallantry and risk-of-life in addition – and secondary to – the Medal of Honor. He proposed the idea to President Woodrow Wilson, and the Distinguished Service Cross was authorized in 1918. It was then awarded retroactively to 1917, and several even-older merit medals were upgraded.

Originally, the service cross was established to cover all people who acted on behalf of the U.S. military with extraordinary heroism in a combat situation. But over time, the other military branches created their own service cross medals. Today, second only to the Medal of Honor, there are now four service cross medals for the separate U.S. military branches: the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross, the Navy Cross, the Air Force Cross, and the Coast Guard Cross.

Birth Of Chesty Puller

As a child, Puller enjoyed listening to the tales of Civil War veterans and particularly idolized “Stonewall” Jackson. He had hoped to join in the Border War with Mexico in 1916, but he was too young and his mother wouldn’t consent to let him go.

Puller then went to the Virginia Military Institute in 1917, but left the following year to join in World War I. Hearing tales of the 5th Marines at Belleau Wood, he decided to join the Marines and “go where the guns are.” Puller never saw action in the war, but went on to attend the non-commissioned officer school and Officer Candidates School.

As American forces were reduced following the war, Puller was put on inactive status. He later received orders to go to Haiti, where he took part in more than 40 fights over five years against Caco rebels. Then in 1928, Puller was sent to Nicaragua for a similar mission. While there, he received two Navy Crosses. The first was for leading “five successive engagements against superior numbers of armed bandit forces.” The second was for leading Nicaraguan National Guardsmen in the final battle of the rebellion. After that conflict, Puller went to China twice to command Chinese and American Marines.

Just before World War II, Puller was placed in command of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines. In 1942, they landed on Guadalcanal, where Puller earned his third Navy Cross. In one action alone, his Marines killed 1,400 hostile troops, held ground until reinforcements arrived, and suffered fewer than 70 casualties. He earned his fourth Navy Cross for action on Cape Gloucester, New Britain, in 1944. When the leaders of two battalions were wounded, he took over and moved through heavy fire to command their units.

Puller returned to the US in November 1944 and held a series of leadership positions. Then in 1950, as America entered the Korean War, he was called upon once again to lead Marines into battle. Puller was over 50 years old when he took part in the September 1950 Battle of Inchon as commander of the 1st Marine Regiment. Puller led his men fearlessly as the UN forces, made up mostly of Americans, advanced north following the retreating North Korean People’s Army.

By December, they were near the Chosin Reservoir when China’s People’s Volunteer Army poured over the China-North Korea border and surrounded the UN army. When Puller was updated about the dire situation he said, “We’ve been looking for the enemy for some time now. We’ve finally found him. We’re surrounded. That simplifies things.” His Marines managed to keep supply lines open and acted as rear guard during withdrawal. They destroyed seven of the enemy’s 22 divisions and inflicted heavy casualties on the rest. Puller was awarded his fifth Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism during the operation, the most of any Marine in US history.

After completing his tour of duty in Korea, Puller trained Marines in California. He suffered a stroke and retired in 1955. He died on October 11, 1972. Puller was and still remains a popular figure and spirit de corps in the Marines. During boot camp, it’s common for Marines to say “Good night, Chesty, wherever you are!” They may also exclaim, “Chesty Puller never quit!” or tell each other while doing push-ups “do one for Chesty!” There’s also “It was good for Chesty Puller and it’s good enough for me” as well as “Tell Chesty Puller I did my best.”