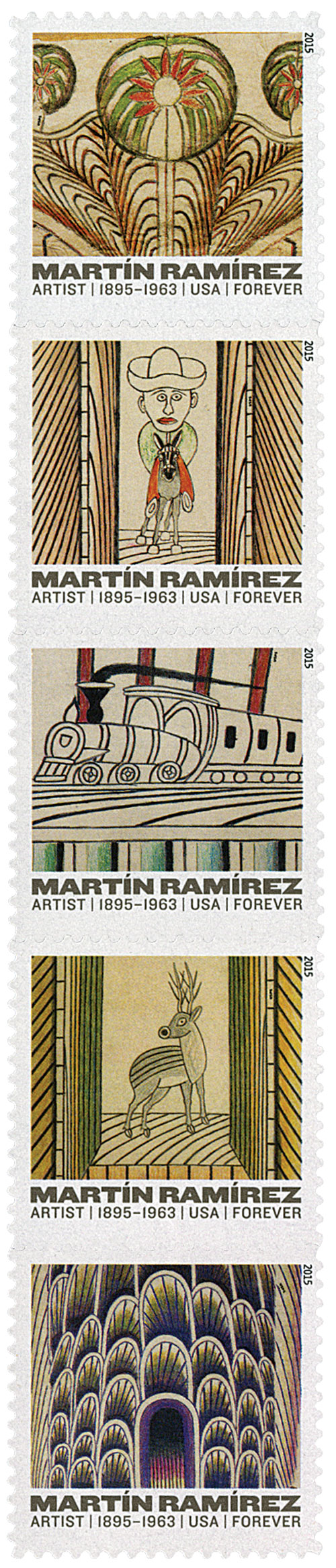

# 4968-72 - 2015 First-Class Forever Stamp - Martin Ramirez (1895-1963)

Birth Of MartÃn RamÃrez

Artist MartÃn RamÃrez was born on January 30, 1895, in Rincón de Velázquez, Tepatitlán, Jalisco, Mexico.

RamÃrez came to America in 1925 seeking a better life. Instead he faced more hardship. Jobs were difficult to find in California during the Great Depression, and being unable to speak English further reduced his chances of finding work.

Ramirez worked on the railroads for five years, but was eventually unemployed. When RamÃrez was found homeless and did not speak, he was sent to a hospital. Diagnosed as a schizophrenic, RamÃrez became a lifelong resident of DeWitt State Hospital. It was there he created art from discarded and improvised materials.

RamÃrez used a number of unusual art supplies – fruit juice, shoe polish, junk mail, paper bags, and examining table paper. To make a surface large enough for his drawings, he glued scraps of discarded paper together using mashed potatoes and saliva. The collage of paper became not only the canvas for his work, but many times was incorporated into the design. Advertisements from car companies and pictures cut from magazines became part of his art. He improvised for additional supplies as well, crushing crayons in homemade pots to make paint.

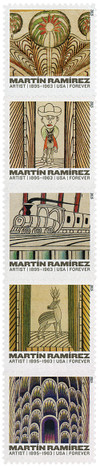

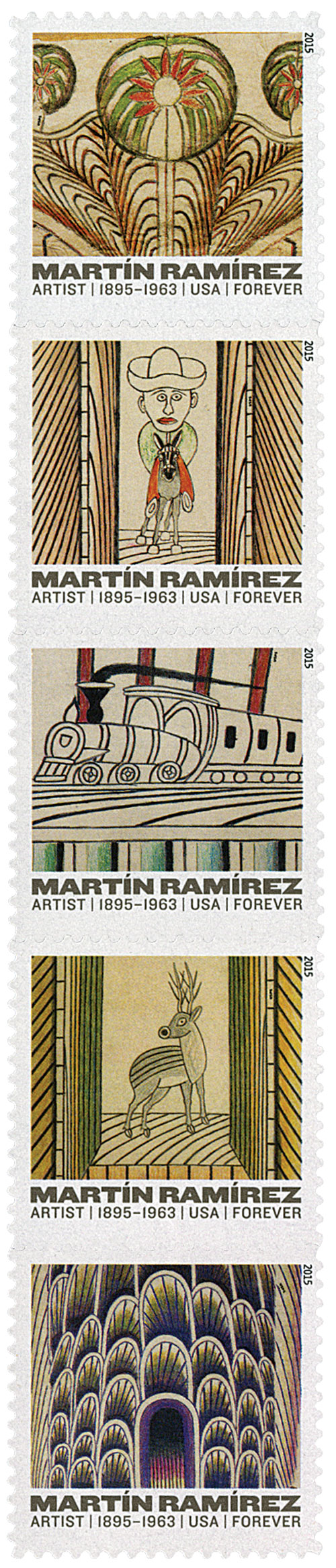

The art that resulted from these primitive supplies was surprisingly skillful and intricate. RamÃrez showed the skill of a draftsman with his parallel lines and curves. He repeated his patterns precisely on large-scale pieces. Even though RamÃrez spent most of his adult life in the United States, much of his work seems to reflect memories of Mexico. He also frequently portrayed images of automobiles, highways, and trains, reminiscent of the industrialized nation he encountered upon moving to the US in 1925. With recurring themes of religious symbols, burros, and trains, RamÃrez’s paintings used perspective and patterns to make masterpieces of which only the artist himself knew the true meaning.

RamÃrez’s work may have been lost forever if it had not been for Tarmo Pasto. A professor of psychology and art at Sacramento State College, Pasto visited DeWitt State Hospital to do research. When RamÃrez showed him some of his work, the professor recognized the artist’s extraordinary talent.

Pasto saved about 300 pieces of RamÃrez’s art in the following years. He showed them to his classes and other professors. Pasto soon began organizing solo shows for colleges in California, then at Syracuse University in New York. The psychologist gave RamÃrez real supplies, so he no longer had to improvise for paint and canvas. In 1955, Pasto sent some drawings to the director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, but no exhibition was ever scheduled. RamÃrez died on February 17, 1963.

Pasto saved RamÃrez’s art, and in 1968, another teacher at Sacramento found his work in storage bins. He and Pasto organized the first gallery exhibition of the artist’s work. Then in 2007, RamÃrez was the focus of a major retrospective at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City. A critic for The New York Times once called MartÃn RamÃrez “one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.” Many of RamÃrez’s originals are now privately owned, and when they do come up for sale they can command a hefty price – some well into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Click here to view some of RamÃrez’s art.

Birth Of MartÃn RamÃrez

Artist MartÃn RamÃrez was born on January 30, 1895, in Rincón de Velázquez, Tepatitlán, Jalisco, Mexico.

RamÃrez came to America in 1925 seeking a better life. Instead he faced more hardship. Jobs were difficult to find in California during the Great Depression, and being unable to speak English further reduced his chances of finding work.

Ramirez worked on the railroads for five years, but was eventually unemployed. When RamÃrez was found homeless and did not speak, he was sent to a hospital. Diagnosed as a schizophrenic, RamÃrez became a lifelong resident of DeWitt State Hospital. It was there he created art from discarded and improvised materials.

RamÃrez used a number of unusual art supplies – fruit juice, shoe polish, junk mail, paper bags, and examining table paper. To make a surface large enough for his drawings, he glued scraps of discarded paper together using mashed potatoes and saliva. The collage of paper became not only the canvas for his work, but many times was incorporated into the design. Advertisements from car companies and pictures cut from magazines became part of his art. He improvised for additional supplies as well, crushing crayons in homemade pots to make paint.

The art that resulted from these primitive supplies was surprisingly skillful and intricate. RamÃrez showed the skill of a draftsman with his parallel lines and curves. He repeated his patterns precisely on large-scale pieces. Even though RamÃrez spent most of his adult life in the United States, much of his work seems to reflect memories of Mexico. He also frequently portrayed images of automobiles, highways, and trains, reminiscent of the industrialized nation he encountered upon moving to the US in 1925. With recurring themes of religious symbols, burros, and trains, RamÃrez’s paintings used perspective and patterns to make masterpieces of which only the artist himself knew the true meaning.

RamÃrez’s work may have been lost forever if it had not been for Tarmo Pasto. A professor of psychology and art at Sacramento State College, Pasto visited DeWitt State Hospital to do research. When RamÃrez showed him some of his work, the professor recognized the artist’s extraordinary talent.

Pasto saved about 300 pieces of RamÃrez’s art in the following years. He showed them to his classes and other professors. Pasto soon began organizing solo shows for colleges in California, then at Syracuse University in New York. The psychologist gave RamÃrez real supplies, so he no longer had to improvise for paint and canvas. In 1955, Pasto sent some drawings to the director of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, but no exhibition was ever scheduled. RamÃrez died on February 17, 1963.

Pasto saved RamÃrez’s art, and in 1968, another teacher at Sacramento found his work in storage bins. He and Pasto organized the first gallery exhibition of the artist’s work. Then in 2007, RamÃrez was the focus of a major retrospective at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City. A critic for The New York Times once called MartÃn RamÃrez “one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.” Many of RamÃrez’s originals are now privately owned, and when they do come up for sale they can command a hefty price – some well into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Click here to view some of RamÃrez’s art.