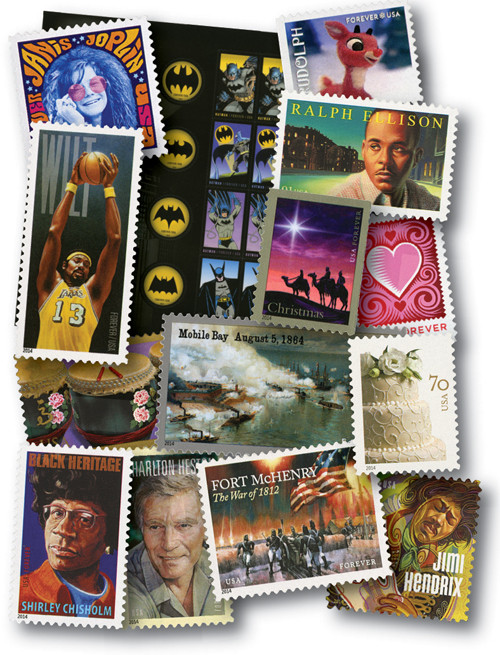

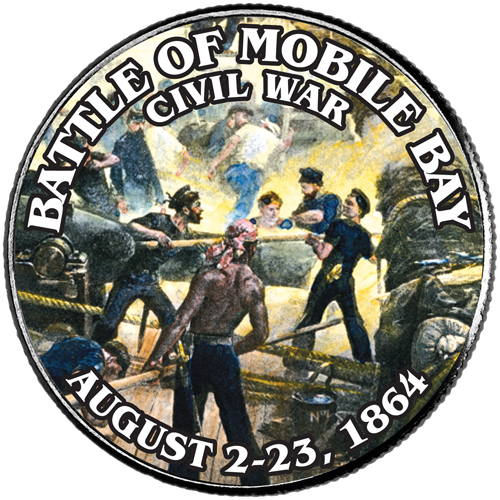

# 4911 - 2014 First-Class Forever Stamp - The Civil War Sesquicentennial, 1864: The Battle of Mobile Bay

Battle Of Mobile Bay Begins

On August 5, 1864, Admiral David Farragut led a successful naval attack that led to a Union victory at Mobile Bay, Alabama.

Mobile Bay was the last important harbor held by the Confederacy. It was deep enough for ocean-going vessels to navigate, and three forts protected the opening. The city of Mobile, at the head of the bay, was the center of blockade running in the Gulf of Mexico, which continued in spite of efforts by the Union to stop it. In August 1864, the Union’s Rear Admiral David Farragut was determined to take control of the bay and put an end to the blockade-runners.

A long, narrow peninsula marked the opening of the bay. In 1834, the U.S. built Fort Morgan at its tip to protect the port from enemies. During the Civil War, the Confederacy took control of Mobile Bay and reinforced this fort, as well as two smaller ones that also guarded the entrance.

In addition to the forts, the Confederate Torpedo Bureau planted a line of naval mines (known as torpedoes) across the main channel, leaving an opening near Fort Morgan. Blockade-runners safely navigated the opening, but the stronghold’s guns hit Union vessels attempting to pass through.

The Confederate fleet stationed in the bay consisted of three small gunboats and the CSS Tennessee, an ironclad with a ram. Admiral Franklin Buchanan commanded the ships. He had been the flag officer aboard the Virginia in the first battle of ironclads in 1862. Because of his heroic actions at the time, he became the Confederacy’s first admiral.

Farragut and the West Gulf Blockading Squadron had previously been successful in taking control of the Mississippi River. The admiral’s attention now turned to Mobile Bay. His fleet was much larger than Buchanan’s, and the lessons Farragut had learned during the Mississippi battles would serve him well this time.

The battle required the assistance of the army. The commander of the Military Division of West Mississippi estimated he needed 5,000 troops to land behind the forts and cut off communications with Mobile. General-in-Chief Ulysses Grant needed all available soldiers for his campaign in Virginia; so many from this area were sent to his aid. The remaining men were enough to take the forts but not the city of Mobile. Some of the troops were signal corpsmen who went aboard Farragut’s ships in order for the navy and army to communicate with each other.

On August 3, some 1,500 Union troops under the command of General Gordon Granger landed on the far side of Dauphin Island, the location of Fort Gaines, the second-largest fort. By the next evening, they had formed skirmish lines less than a half-mile from the fort.

While the army prepared for battle on land, Farragut was getting his fleet ready for the dangerous venture past Fort Morgan. He had run his fleet past the guns of the forts protecting New Orleans and would use the same strategy here. The admiral’s 14 wooden ships were lashed together in pairs. If one became disabled, the other could drag it through the channel. The four ironclads were positioned closer to the fort to protect the wooden ships from artillery fire.

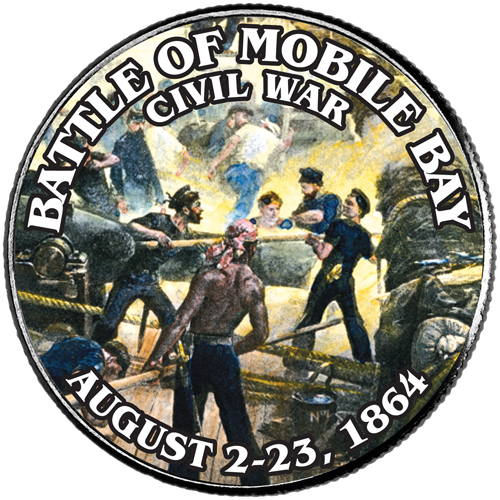

At dawn on August 5, the fleet began its mission. The USS Tecumseh led the ironclads and the Brooklyn and Octorara were the first wooden-hulled ships in the line. At 6:47 a.m., Tecumseh fired the first shot and the battle began. As the ironclad was passing the fort, it steered too close to the minefield, detonating a torpedo. It sunk within minutes. The commander of the Brooklyn stopped his ship to await orders from Farragut. The admiral ordered that his ship, the Hartford, be steered around it and into the lead. This took his ship over the minefield. When asked about sailing over the mines, Farragut allegedly shouted, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” His daring command paid off, and the rest of the ships made it safely past Fort Morgan.

Farragut ordered the wooden vessels to be unlashed and to pursue the wooden Confederate boats. One was captured almost immediately. Another was beached, and then burned by its crew. The third sought the protection of Fort Morgan’s guns. The final Southern ship, the ironclad Tennessee, faced the entire Union fleet. Rather than moving to safety, Admiral Buchanan turned his vessel and sailed full-steam into the midst. He tried to ram the Northern ships, but his vessel was too slow. The smokestack was shot and the boiler could not build up pressure needed to run the engines. The chains connected to the rudder were damaged, so the ship could not be steered. In addition, the shutters on the gun ports were jammed shut so the artillery inside was useless. The Tennessee surrendered about three hours after the first shot was fired.

Enemy ships no longer threatened the Union Navy, so Farragut began the attack on the forts. He sent one of the ironclads to bombard Fort Powell, the smallest of the three. The commander of the fort realized resistance was futile, so his men spiked the guns and blew up the magazines. They then waded ashore and made their way to Mobile.

The Northern ground troops went into action at Fort Gaines. Sand dunes shielded their artillery, making it easier to bombard the stronghold from behind. The fort surrendered on August 8. Granger then moved his men behind Fort Morgan, cutting off all communications with Mobile. The Confederates held out until August 23, when the white flag of surrender was raised over the last of the three forts.

Though the important city of Mobile remained part of the Confederacy, Mobile Bay was now in Union hands and closed to blockade-runners. For the part he played in the victory, Farragut was given a $50,000 bonus and promoted to vice admiral.

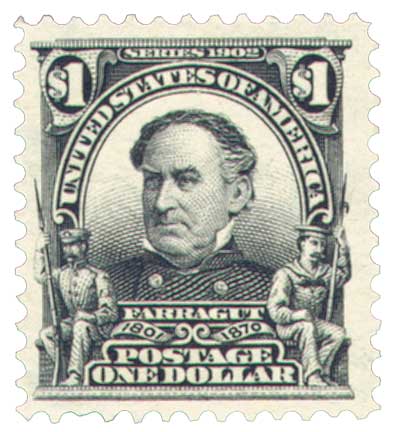

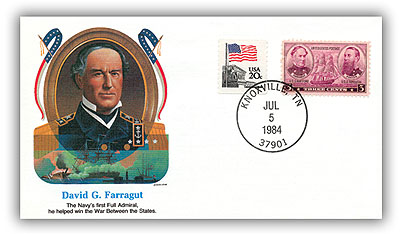

Birth Of David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut was born in Campbell’s Station (now Farragut), Tennessee, on July 5, 1801.

Born to a veteran of the Continental Navy, Farragut’s first name was initially James. After his mother died from yellow fever, Farragut’s father sent him to live with friends in 1808, whom he believed would provide better care. So Farragut was raised by naval officer David Porter and was a foster brother to David Dixon Porter and William D. Porter. In 1812, Farragut adopted David as his first name in honor of his foster father.

Farragut began his naval career at the age of nine as a midshipman. Within two years he was a prize master and then served aboard the USS Essex during its capture of the HMS Alert. From there, he went on to aid in the establishment of America’s first naval base and colony in the Pacific, Fort Madison.

After the War of 1812, Farragut served on various ships, mostly in the Mediterranean. In 1823, he sailed to the Caribbean to help fight pirates, and during the Mexican-American War, he saw duty on both sea and shore. Following that war, he was tasked with establishing Mare Island Navy Yard in California.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Farragut showed his loyalty to the Union when he gave up his home in Norfolk, Virginia, to fight for the North. He was then placed in command of the campaign to capture New Orleans and gain control of the Mississippi as part of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. He took the USS Hartford as his flagship.

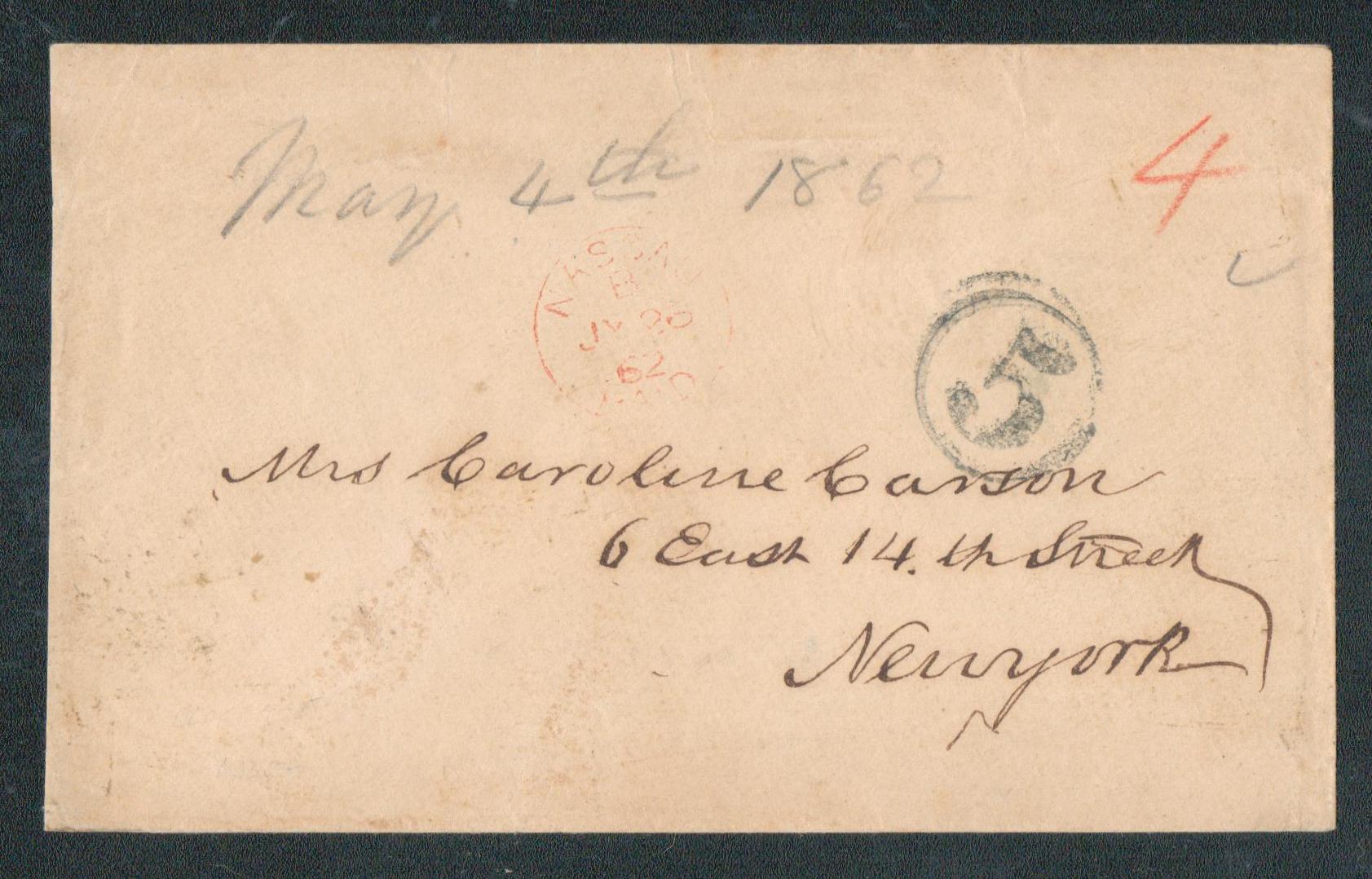

On April 18, 1862, the ships began bombing two forts near New Orleans. The bombardment lasted for five days with no signs of progress. Farragut was commanding the squadron and decided to sail past the forts at night. His successful plan forced the surrender of Fort Jackson, Fort St. Philip, and New Orleans. For two years he blockaded the Gulf Coast and controlled river traffic.

In 1864, the Confederacy still held the port of Mobile Bay. It was heavily mined with anchored bombs known as torpedoes and protected by two forts. That August, Farragut was ordered to capture Mobile Bay. When his ironclad Tecumseh was sunk by a torpedo, Farragut was warned that Fort Morgan’s guns, as well as those from the Confederate Tennessee, were directed at his fleet. “Damn the torpedoes,” he replied, “Full speed ahead!”

Watching the enemy approach, Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan readied his flagship, the ironclad CSS Tennessee. Mobile Bay was the last Confederate-controlled port east of the Mississippi and Buchanan had to defend it.

Battle Of Mobile Bay Begins

On August 5, 1864, Admiral David Farragut led a successful naval attack that led to a Union victory at Mobile Bay, Alabama.

Mobile Bay was the last important harbor held by the Confederacy. It was deep enough for ocean-going vessels to navigate, and three forts protected the opening. The city of Mobile, at the head of the bay, was the center of blockade running in the Gulf of Mexico, which continued in spite of efforts by the Union to stop it. In August 1864, the Union’s Rear Admiral David Farragut was determined to take control of the bay and put an end to the blockade-runners.

A long, narrow peninsula marked the opening of the bay. In 1834, the U.S. built Fort Morgan at its tip to protect the port from enemies. During the Civil War, the Confederacy took control of Mobile Bay and reinforced this fort, as well as two smaller ones that also guarded the entrance.

In addition to the forts, the Confederate Torpedo Bureau planted a line of naval mines (known as torpedoes) across the main channel, leaving an opening near Fort Morgan. Blockade-runners safely navigated the opening, but the stronghold’s guns hit Union vessels attempting to pass through.

The Confederate fleet stationed in the bay consisted of three small gunboats and the CSS Tennessee, an ironclad with a ram. Admiral Franklin Buchanan commanded the ships. He had been the flag officer aboard the Virginia in the first battle of ironclads in 1862. Because of his heroic actions at the time, he became the Confederacy’s first admiral.

Farragut and the West Gulf Blockading Squadron had previously been successful in taking control of the Mississippi River. The admiral’s attention now turned to Mobile Bay. His fleet was much larger than Buchanan’s, and the lessons Farragut had learned during the Mississippi battles would serve him well this time.

The battle required the assistance of the army. The commander of the Military Division of West Mississippi estimated he needed 5,000 troops to land behind the forts and cut off communications with Mobile. General-in-Chief Ulysses Grant needed all available soldiers for his campaign in Virginia; so many from this area were sent to his aid. The remaining men were enough to take the forts but not the city of Mobile. Some of the troops were signal corpsmen who went aboard Farragut’s ships in order for the navy and army to communicate with each other.

On August 3, some 1,500 Union troops under the command of General Gordon Granger landed on the far side of Dauphin Island, the location of Fort Gaines, the second-largest fort. By the next evening, they had formed skirmish lines less than a half-mile from the fort.

While the army prepared for battle on land, Farragut was getting his fleet ready for the dangerous venture past Fort Morgan. He had run his fleet past the guns of the forts protecting New Orleans and would use the same strategy here. The admiral’s 14 wooden ships were lashed together in pairs. If one became disabled, the other could drag it through the channel. The four ironclads were positioned closer to the fort to protect the wooden ships from artillery fire.

At dawn on August 5, the fleet began its mission. The USS Tecumseh led the ironclads and the Brooklyn and Octorara were the first wooden-hulled ships in the line. At 6:47 a.m., Tecumseh fired the first shot and the battle began. As the ironclad was passing the fort, it steered too close to the minefield, detonating a torpedo. It sunk within minutes. The commander of the Brooklyn stopped his ship to await orders from Farragut. The admiral ordered that his ship, the Hartford, be steered around it and into the lead. This took his ship over the minefield. When asked about sailing over the mines, Farragut allegedly shouted, “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!” His daring command paid off, and the rest of the ships made it safely past Fort Morgan.

Farragut ordered the wooden vessels to be unlashed and to pursue the wooden Confederate boats. One was captured almost immediately. Another was beached, and then burned by its crew. The third sought the protection of Fort Morgan’s guns. The final Southern ship, the ironclad Tennessee, faced the entire Union fleet. Rather than moving to safety, Admiral Buchanan turned his vessel and sailed full-steam into the midst. He tried to ram the Northern ships, but his vessel was too slow. The smokestack was shot and the boiler could not build up pressure needed to run the engines. The chains connected to the rudder were damaged, so the ship could not be steered. In addition, the shutters on the gun ports were jammed shut so the artillery inside was useless. The Tennessee surrendered about three hours after the first shot was fired.

Enemy ships no longer threatened the Union Navy, so Farragut began the attack on the forts. He sent one of the ironclads to bombard Fort Powell, the smallest of the three. The commander of the fort realized resistance was futile, so his men spiked the guns and blew up the magazines. They then waded ashore and made their way to Mobile.

The Northern ground troops went into action at Fort Gaines. Sand dunes shielded their artillery, making it easier to bombard the stronghold from behind. The fort surrendered on August 8. Granger then moved his men behind Fort Morgan, cutting off all communications with Mobile. The Confederates held out until August 23, when the white flag of surrender was raised over the last of the three forts.

Though the important city of Mobile remained part of the Confederacy, Mobile Bay was now in Union hands and closed to blockade-runners. For the part he played in the victory, Farragut was given a $50,000 bonus and promoted to vice admiral.

Birth Of David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut was born in Campbell’s Station (now Farragut), Tennessee, on July 5, 1801.

Born to a veteran of the Continental Navy, Farragut’s first name was initially James. After his mother died from yellow fever, Farragut’s father sent him to live with friends in 1808, whom he believed would provide better care. So Farragut was raised by naval officer David Porter and was a foster brother to David Dixon Porter and William D. Porter. In 1812, Farragut adopted David as his first name in honor of his foster father.

Farragut began his naval career at the age of nine as a midshipman. Within two years he was a prize master and then served aboard the USS Essex during its capture of the HMS Alert. From there, he went on to aid in the establishment of America’s first naval base and colony in the Pacific, Fort Madison.

After the War of 1812, Farragut served on various ships, mostly in the Mediterranean. In 1823, he sailed to the Caribbean to help fight pirates, and during the Mexican-American War, he saw duty on both sea and shore. Following that war, he was tasked with establishing Mare Island Navy Yard in California.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Farragut showed his loyalty to the Union when he gave up his home in Norfolk, Virginia, to fight for the North. He was then placed in command of the campaign to capture New Orleans and gain control of the Mississippi as part of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. He took the USS Hartford as his flagship.

On April 18, 1862, the ships began bombing two forts near New Orleans. The bombardment lasted for five days with no signs of progress. Farragut was commanding the squadron and decided to sail past the forts at night. His successful plan forced the surrender of Fort Jackson, Fort St. Philip, and New Orleans. For two years he blockaded the Gulf Coast and controlled river traffic.

In 1864, the Confederacy still held the port of Mobile Bay. It was heavily mined with anchored bombs known as torpedoes and protected by two forts. That August, Farragut was ordered to capture Mobile Bay. When his ironclad Tecumseh was sunk by a torpedo, Farragut was warned that Fort Morgan’s guns, as well as those from the Confederate Tennessee, were directed at his fleet. “Damn the torpedoes,” he replied, “Full speed ahead!”

Watching the enemy approach, Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan readied his flagship, the ironclad CSS Tennessee. Mobile Bay was the last Confederate-controlled port east of the Mississippi and Buchanan had to defend it.