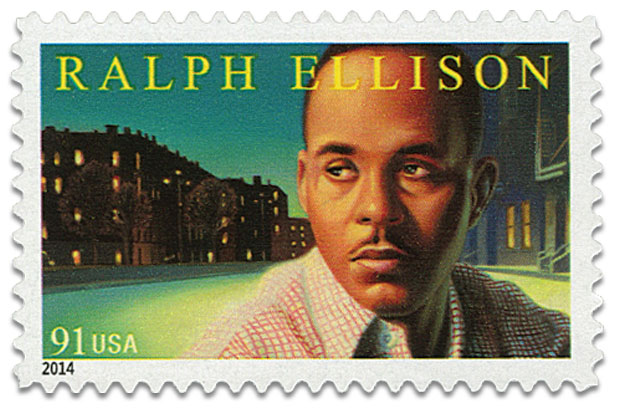

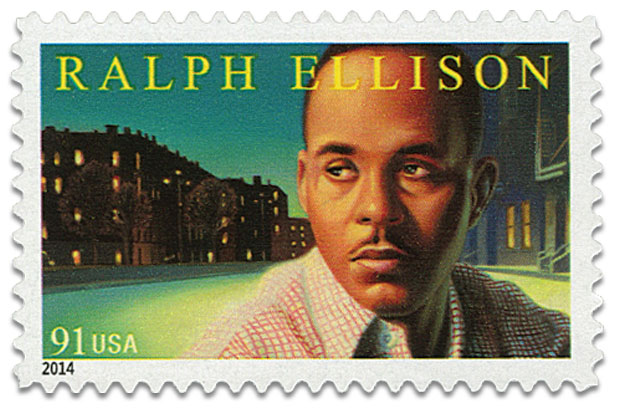

# 4866 - 2014 91c Literary Arts: Ralph Ellison

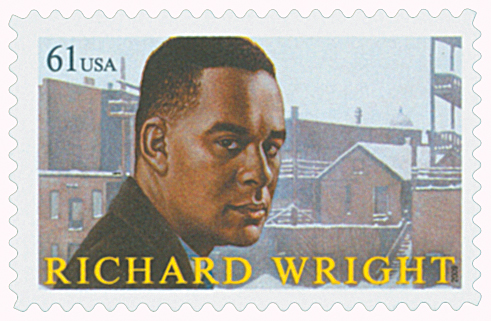

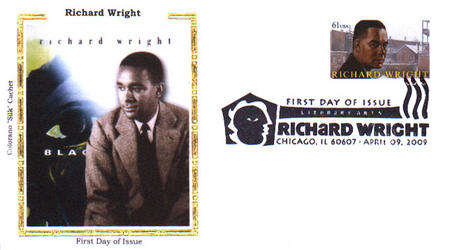

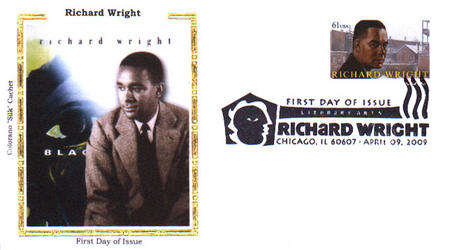

Birth Of Richard Wright

Wright’s grandparents had been born into slavery and were freed during the Civil War, with both of his grandfathers serving in the Union Army and Navy.

Wright’s father left the family when he was six years old and he spent several years of his childhood moving around with his mother and siblings. By the time he was 12, he hadn’t completed a full year of school.

Wright finally received regular schooling beginning in 1920 after he and his family moved in with his grandmother in Jackson, Mississippi. He published his first story in eighth grade, “The Voodoo of Hell’s Half-Acre” in the local paper Southern Register. Excelling in school, he was named the valedictorian of his junior high class. The principal had wanted him to read a prepared speech, but Wright was adamant that he read his own speech, despite pressure from his family and even his classmates.

Wright briefly attended high school but left to work to make money for his family. In 1927, the family moved to Chicago in search of a better life. Wright worked as a postal clerk until he was fired during the Depression. He wrote his first novel, Cesspool, in 1935, though it wouldn’t be published until after his death. While in Chicago, Wright joined the city’s Communist Party and contributed several “revolutionary” poems to The New Masses magazine of the party. Faced with racial discrimination even there, Wright later left the party.

Wright moved to New York in 1937 and worked on the Federal Writers’ Project. The following year, he gained national acclaim for his collection of four short stories, Uncle Tom’s Children. He followed that with Native Son in 1940.

Native Son was the first book by an African American author to be selected by the Book of the Month Club. It was also the first best selling novel by a black writer. The following year, Native Son was turned into a play, which was directed by Orson Welles, and Wright won the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal. In 1945, Wright published his memoir, Black Boy, which recounted his life up until his move to Chicago.

After visiting Canada for a few months, Wright decided to move to Paris in 1946 and was made a French citizen the following year. He visited Europe, Africa, and Asia and used his travels as inspiration for his nonfiction works. He continued to write until his death on November 28, 1960. After his death, many of his unpublished works were released.

Birth Of Richard Wright

Wright’s grandparents had been born into slavery and were freed during the Civil War, with both of his grandfathers serving in the Union Army and Navy.

Wright’s father left the family when he was six years old and he spent several years of his childhood moving around with his mother and siblings. By the time he was 12, he hadn’t completed a full year of school.

Wright finally received regular schooling beginning in 1920 after he and his family moved in with his grandmother in Jackson, Mississippi. He published his first story in eighth grade, “The Voodoo of Hell’s Half-Acre” in the local paper Southern Register. Excelling in school, he was named the valedictorian of his junior high class. The principal had wanted him to read a prepared speech, but Wright was adamant that he read his own speech, despite pressure from his family and even his classmates.

Wright briefly attended high school but left to work to make money for his family. In 1927, the family moved to Chicago in search of a better life. Wright worked as a postal clerk until he was fired during the Depression. He wrote his first novel, Cesspool, in 1935, though it wouldn’t be published until after his death. While in Chicago, Wright joined the city’s Communist Party and contributed several “revolutionary” poems to The New Masses magazine of the party. Faced with racial discrimination even there, Wright later left the party.

Wright moved to New York in 1937 and worked on the Federal Writers’ Project. The following year, he gained national acclaim for his collection of four short stories, Uncle Tom’s Children. He followed that with Native Son in 1940.

Native Son was the first book by an African American author to be selected by the Book of the Month Club. It was also the first best selling novel by a black writer. The following year, Native Son was turned into a play, which was directed by Orson Welles, and Wright won the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal. In 1945, Wright published his memoir, Black Boy, which recounted his life up until his move to Chicago.

After visiting Canada for a few months, Wright decided to move to Paris in 1946 and was made a French citizen the following year. He visited Europe, Africa, and Asia and used his travels as inspiration for his nonfiction works. He continued to write until his death on November 28, 1960. After his death, many of his unpublished works were released.