# 4801e - 2013 First-Class Forever Stamp - Made in America: Linotype Operator

US #4801e

2013 Linotype Operator – Made in America

- One of 12 stamps celebrating the industrial workers who brought America into a new age

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Made in America

Value: 46¢ First Class Mail Rate (Forever)

First Day of Issue: August 8, 2013

First Day City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 2,500,000

Printed by: Avery Dennison

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 12

Why the stamp was issued: To honor linotype operators and their impact on the printing industry.

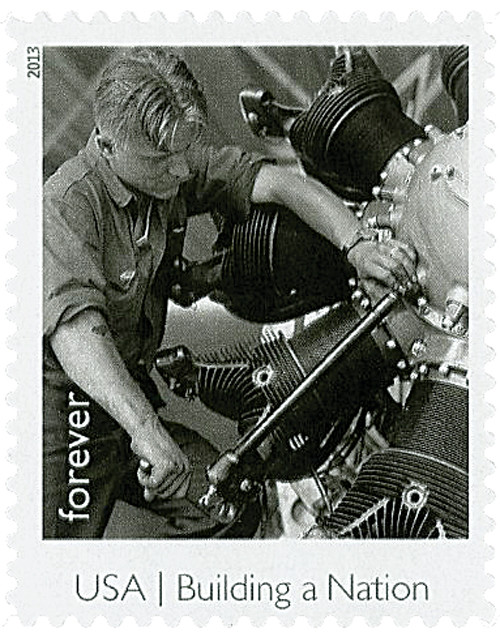

About the stamp design: Pictures a black and white vintage photograph by Lewis Hines of a woman operating a linotype machine.

First Day City: The First Day of Issue Ceremony was held at the Frances Perkins Building, part of the Department of Labor in Washington, DC.

About the Made in America set: Includes 12 different stamp designs picturing black and white vintage photographs of male and female industrial workers. Eleven were taken by photographer Lewis Hine, with the twelfth by Margaret Bourke-White. The USPS said “Stamps are like a miniature American portrait gallery. They are an expression of our values and a connection to our past. That’s why it’s so fitting that this series depicts Americans at work. These iconic images tell a powerful story about American economic strength and prosperity. These men and women and millions like them really did build a nation.”

History the stamp represents: The invention of the linotype machine revolutionized the printing industry. A newspaper that took a week to produce using hand composition could now be printed in a day.

Before 1884, printmakers produced a page of print by placing one letter at a time into a form. That year, a new print machine was invented which produced a line of type all at once. The linotype keyboard had 90 keys that, when pressed, allowed a brass letter to be released to form words. When a line was completed, a metal “slug” was cast from the line. The slugs were then used to form a page of print.

Experienced operators produced from four to seven lines each minute. In addition to knowing how to run the machine, the position also required a knowledge of English because long words had to be divided correctly when they were at the end of a line. In the early 1900s, a linotype operator was one of the few occupations at which women worked alongside men and earned the same wage.

Before the linotype machine, newspapers were produced weekly and had no more than eight pages. With the help of linotype machines, longer newspapers were printed daily, and knowledge became more accessible to the average citizen.

US #4801e

2013 Linotype Operator – Made in America

- One of 12 stamps celebrating the industrial workers who brought America into a new age

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Made in America

Value: 46¢ First Class Mail Rate (Forever)

First Day of Issue: August 8, 2013

First Day City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity Issued: 2,500,000

Printed by: Avery Dennison

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 12

Why the stamp was issued: To honor linotype operators and their impact on the printing industry.

About the stamp design: Pictures a black and white vintage photograph by Lewis Hines of a woman operating a linotype machine.

First Day City: The First Day of Issue Ceremony was held at the Frances Perkins Building, part of the Department of Labor in Washington, DC.

About the Made in America set: Includes 12 different stamp designs picturing black and white vintage photographs of male and female industrial workers. Eleven were taken by photographer Lewis Hine, with the twelfth by Margaret Bourke-White. The USPS said “Stamps are like a miniature American portrait gallery. They are an expression of our values and a connection to our past. That’s why it’s so fitting that this series depicts Americans at work. These iconic images tell a powerful story about American economic strength and prosperity. These men and women and millions like them really did build a nation.”

History the stamp represents: The invention of the linotype machine revolutionized the printing industry. A newspaper that took a week to produce using hand composition could now be printed in a day.

Before 1884, printmakers produced a page of print by placing one letter at a time into a form. That year, a new print machine was invented which produced a line of type all at once. The linotype keyboard had 90 keys that, when pressed, allowed a brass letter to be released to form words. When a line was completed, a metal “slug” was cast from the line. The slugs were then used to form a page of print.

Experienced operators produced from four to seven lines each minute. In addition to knowing how to run the machine, the position also required a knowledge of English because long words had to be divided correctly when they were at the end of a line. In the early 1900s, a linotype operator was one of the few occupations at which women worked alongside men and earned the same wage.

Before the linotype machine, newspapers were produced weekly and had no more than eight pages. With the help of linotype machines, longer newspapers were printed daily, and knowledge became more accessible to the average citizen.