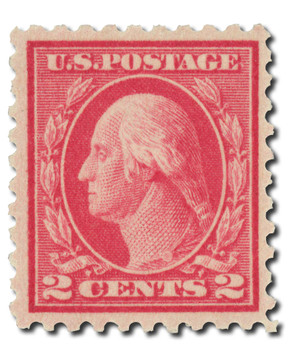

U.S. #479

Series of 1916-17 $2 Madison

Issue Date: March 22, 1917

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 10

Color: Dark blue

The U.S. Postal Service was faced with a sudden and unexpectedly high demand for high-denomination postage stamps early in 1917. The large numbers of heavy machine parts shipped to Russia required high postage amounts. U.S. #479 was also used to send valuable Liberty Bond shipments.

The Post Office did not have time to prepare new designs to meet the need, so the Series of 1902 master dies were used for the $2 Madison and $5 Marshall issues. The original plates and transfer rollers had already been destroyed.

Birth Of Dolley Madison

Our nation’s third First Lady was born Dolley Payne in Piedmont, North Carolina, on May 20, 1768.

Dolley’s family lived in Hanover County, Virginia, where her father was a planter. A bright and outspoken young girl, Dolley was greatly affected by the Boston Massacre, Boston Tea Party, Declaration of Independence, and the suffering at Valley Forge. In 1783, Dolley’s father freed his slaves and moved his family to Philadelphia to give his children better educational opportunities and to be closer to the family’s Quaker roots.

On January 7, 1790, Dolley married John Todd, Jr., a lawyer from Philadelphia. Together, they had two sons, John and William. In 1793, a yellow fever epidemic broke out in Philadelphia. Todd convinced Dolley to move out of the city with their son John, while he remained in the city to help the sick. Todd and their son William died shortly after.

The following year, Dolley returned to Philadelphia with her son. At this time, her friend Aaron Burr, a regular guest at the boarding house her mother managed, introduced Dolley to James Madison. On September 14, 1794, Dolley and James were married in Harewood, Virginia.

In 1801, James Madison was appointed Secretary of State, a position he held for eight years. During that time, President Thomas Jefferson, whose wife had died before he was elected, asked Dolley to fulfill some of the duties usually performed by the First Lady. She planned and oversaw a number of functions, quickly becoming well known for her style, hospitality, and energetic personality. During this time, Dolley used her public exposure to enhance fundraising efforts for exploring the Louisiana Territory.

By 1809, Dolley was a popular and well-known hostess and her husband was the newly elected President of the United States. Shortly after the election, the Madisons hosted the first presidential inaugural ball, a tradition that is held to this day.

As the President’s wife and hostess of all social functions at the White House, Dolley put the interests of her country and her husband’s administration first. She possessed remarkable conversational skills that she often used to discover her guests viewpoints on her husband’s policies. She brought a fresh look to the White House, redecorating in a grand and impressive style. Dolley had much of the White House painted, and brought in new American-made furniture with a Greek style. She also adorned the walls with paintings of important Americans and American themes.

The Madisons and their guests were only able to enjoy the renovations for a short time. On August 24-25, 1814, British troops invaded Washington, D.C., and set fire to the White House. Dolley refused to leave quietly. She stayed at the White House long after many of the American troops retreated, packing a carriage with important items she did not want the British to find or destroy. Among the items rescued was the full-length portrait of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart. She and her husband would spend much of their remaining term ensuring that the White House be rebuilt.

Dolley set a high standard for future First Ladies. She established the role of the First Lady as not just an entertainer, but as a philanthropist as well. One of her projects included a fundraiser to build a home for young, orphaned girls.

In 1817, the Madisons left the White House, returning to their Montpelier, Virginia, plantation. James Madison died in 1836. The following year, Dolley moved back to Washington, D.C., where she was given an honorary seat in Congress. She was the only private citizen to sit on the Congressional floor while it was in session. She was also the first private citizen to send a message via telegraph.

In Dolley’s final years, successive First Ladies consulted her on how to fulfill their duties. Dolley died on July 12, 1849. At her funeral, incumbent President Zachary Taylor referred to her as “First Lady” – the first known use of the phrase referring to the President’s wife – and it has been used for that position ever since.

U.S. #479

Series of 1916-17 $2 Madison

Issue Date: March 22, 1917

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 10

Color: Dark blue

The U.S. Postal Service was faced with a sudden and unexpectedly high demand for high-denomination postage stamps early in 1917. The large numbers of heavy machine parts shipped to Russia required high postage amounts. U.S. #479 was also used to send valuable Liberty Bond shipments.

The Post Office did not have time to prepare new designs to meet the need, so the Series of 1902 master dies were used for the $2 Madison and $5 Marshall issues. The original plates and transfer rollers had already been destroyed.

Birth Of Dolley Madison

Our nation’s third First Lady was born Dolley Payne in Piedmont, North Carolina, on May 20, 1768.

Dolley’s family lived in Hanover County, Virginia, where her father was a planter. A bright and outspoken young girl, Dolley was greatly affected by the Boston Massacre, Boston Tea Party, Declaration of Independence, and the suffering at Valley Forge. In 1783, Dolley’s father freed his slaves and moved his family to Philadelphia to give his children better educational opportunities and to be closer to the family’s Quaker roots.

On January 7, 1790, Dolley married John Todd, Jr., a lawyer from Philadelphia. Together, they had two sons, John and William. In 1793, a yellow fever epidemic broke out in Philadelphia. Todd convinced Dolley to move out of the city with their son John, while he remained in the city to help the sick. Todd and their son William died shortly after.

The following year, Dolley returned to Philadelphia with her son. At this time, her friend Aaron Burr, a regular guest at the boarding house her mother managed, introduced Dolley to James Madison. On September 14, 1794, Dolley and James were married in Harewood, Virginia.

In 1801, James Madison was appointed Secretary of State, a position he held for eight years. During that time, President Thomas Jefferson, whose wife had died before he was elected, asked Dolley to fulfill some of the duties usually performed by the First Lady. She planned and oversaw a number of functions, quickly becoming well known for her style, hospitality, and energetic personality. During this time, Dolley used her public exposure to enhance fundraising efforts for exploring the Louisiana Territory.

By 1809, Dolley was a popular and well-known hostess and her husband was the newly elected President of the United States. Shortly after the election, the Madisons hosted the first presidential inaugural ball, a tradition that is held to this day.

As the President’s wife and hostess of all social functions at the White House, Dolley put the interests of her country and her husband’s administration first. She possessed remarkable conversational skills that she often used to discover her guests viewpoints on her husband’s policies. She brought a fresh look to the White House, redecorating in a grand and impressive style. Dolley had much of the White House painted, and brought in new American-made furniture with a Greek style. She also adorned the walls with paintings of important Americans and American themes.

The Madisons and their guests were only able to enjoy the renovations for a short time. On August 24-25, 1814, British troops invaded Washington, D.C., and set fire to the White House. Dolley refused to leave quietly. She stayed at the White House long after many of the American troops retreated, packing a carriage with important items she did not want the British to find or destroy. Among the items rescued was the full-length portrait of George Washington painted by Gilbert Stuart. She and her husband would spend much of their remaining term ensuring that the White House be rebuilt.

Dolley set a high standard for future First Ladies. She established the role of the First Lady as not just an entertainer, but as a philanthropist as well. One of her projects included a fundraiser to build a home for young, orphaned girls.

In 1817, the Madisons left the White House, returning to their Montpelier, Virginia, plantation. James Madison died in 1836. The following year, Dolley moved back to Washington, D.C., where she was given an honorary seat in Congress. She was the only private citizen to sit on the Congressional floor while it was in session. She was also the first private citizen to send a message via telegraph.

In Dolley’s final years, successive First Ladies consulted her on how to fulfill their duties. Dolley died on July 12, 1849. At her funeral, incumbent President Zachary Taylor referred to her as “First Lady” – the first known use of the phrase referring to the President’s wife – and it has been used for that position ever since.