# 479-80 - 1902 Types of Issue Peforated 10

Are You Missing These 1916-17 Stamps?

Faced with Sudden Need, Printed with 1902 Master Dies

The US Postal Service was faced with a sudden and unexpected demand for high-denomination postage stamps early in 1917. The large numbers of heavy machine parts shipped to Russia required high postage amounts.

The Post Office did not have time to prepare new designs to meet the need, so the Series of 1902 master dies were used for the $2 Madison and $5 Marshall issues. The original plates and transfer rollers had already been destroyed.

The only differences between the 1902 and 1917 issues were that the earlier stamps were perf 12 and printed on double watermark paper. The 1917 issues were perf 10, on unwatermarked paper.

Both of these stamps were used to send valuable Liberty Bond shipments and #480 also paid for fund transfers between postal departments.

Mail During World War I

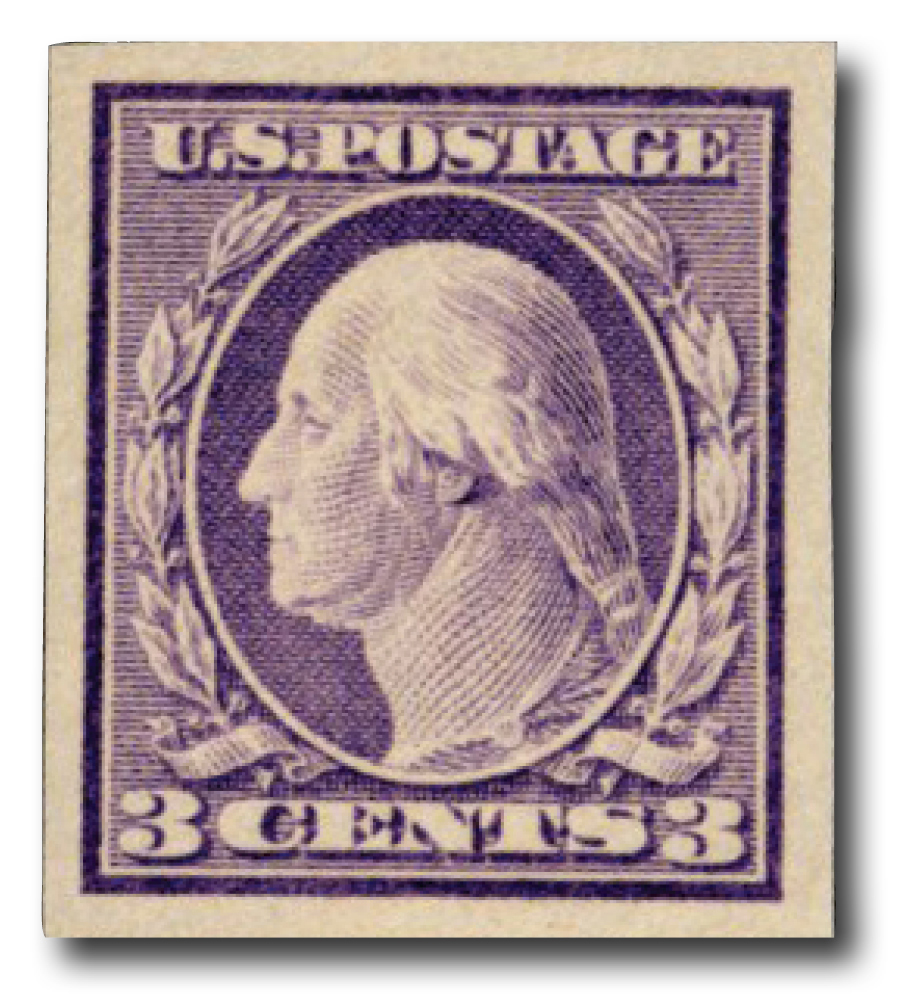

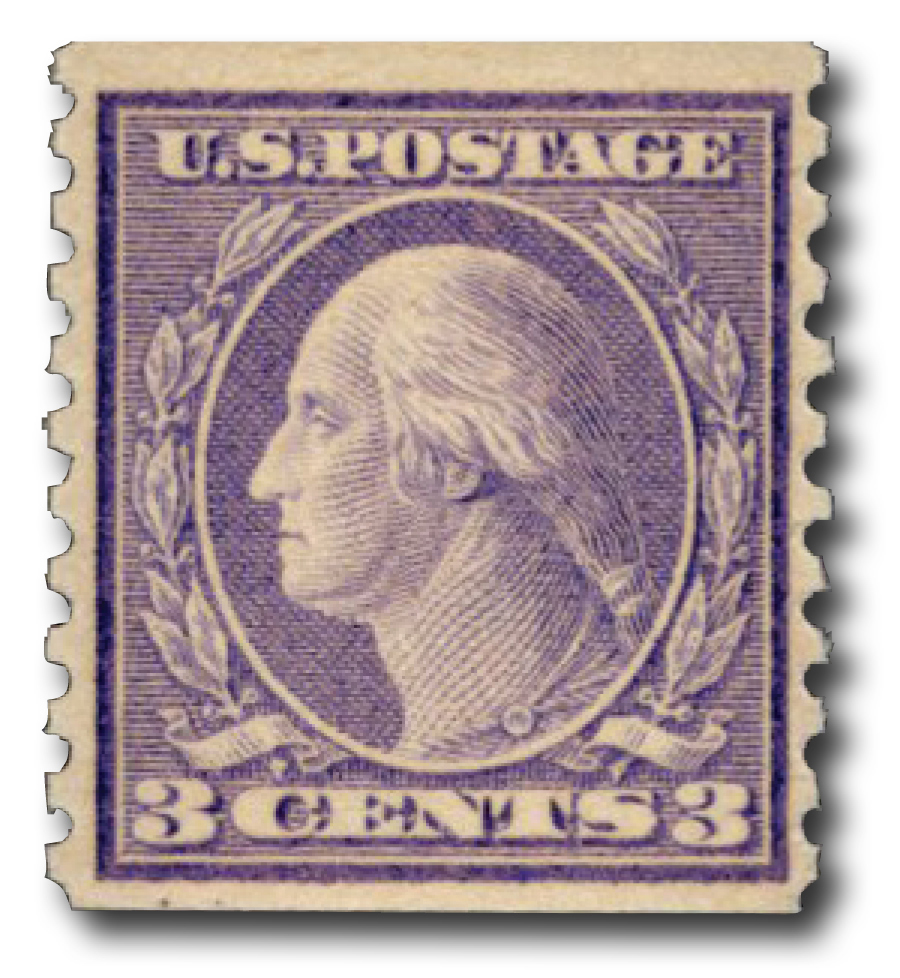

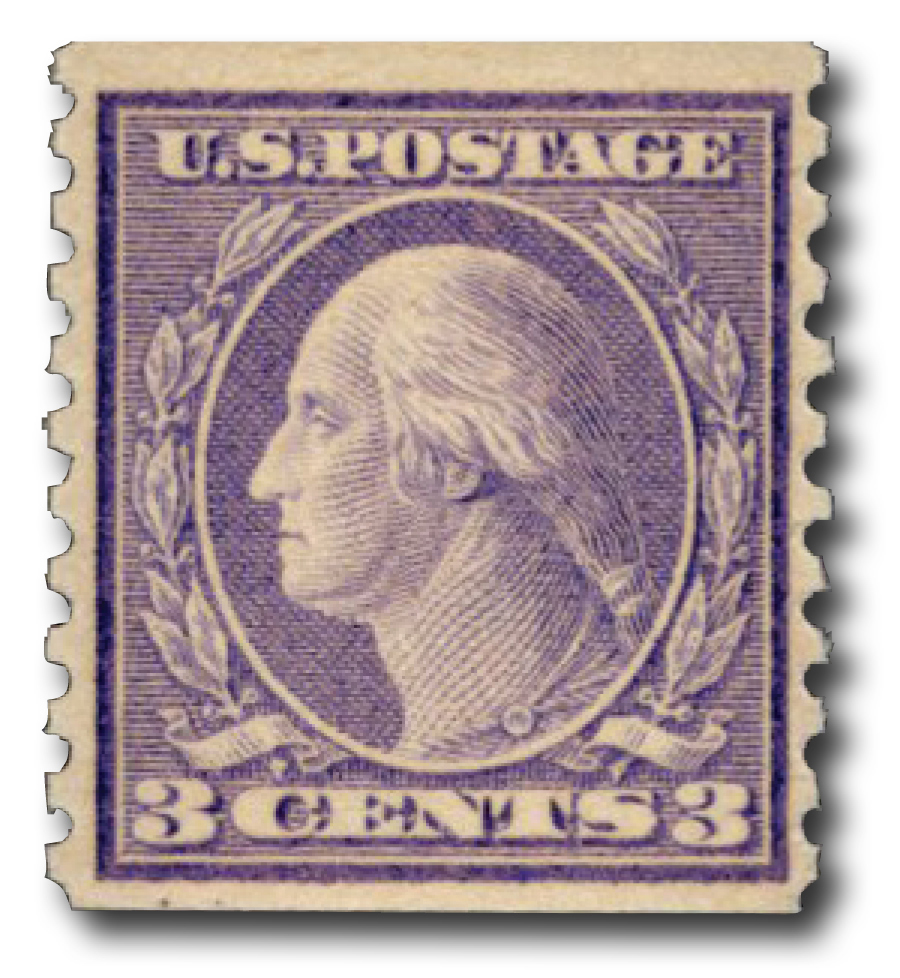

On November 2, 1917, the first class mail rate was raised from 2¢ to 3¢ to help cover the cost of the war effort.

Prior to this, the domestic letter rate for a one-ounce letter had been 2¢ since 1885. However, after the US entered World War I, the Post Office increased the rate to 3¢ on November 2, 1917. The extra 1¢ per ounce was charged as a war tax. The money raised by this tax was transferred to the Treasury’s general fund each month.

Prior to this change, 3¢ stamps saw little use. They didn’t satisfy any direct rate, but were sometimes used along with a 2¢ stamp to make up the 5¢ foreign letter rate or with the 10¢ denomination to pay foreign registration. This change greatly increased the demand for 3¢ stamps – and also for 1¢ stamps, to go with 2¢ stamps and stamped envelopes already purchased.

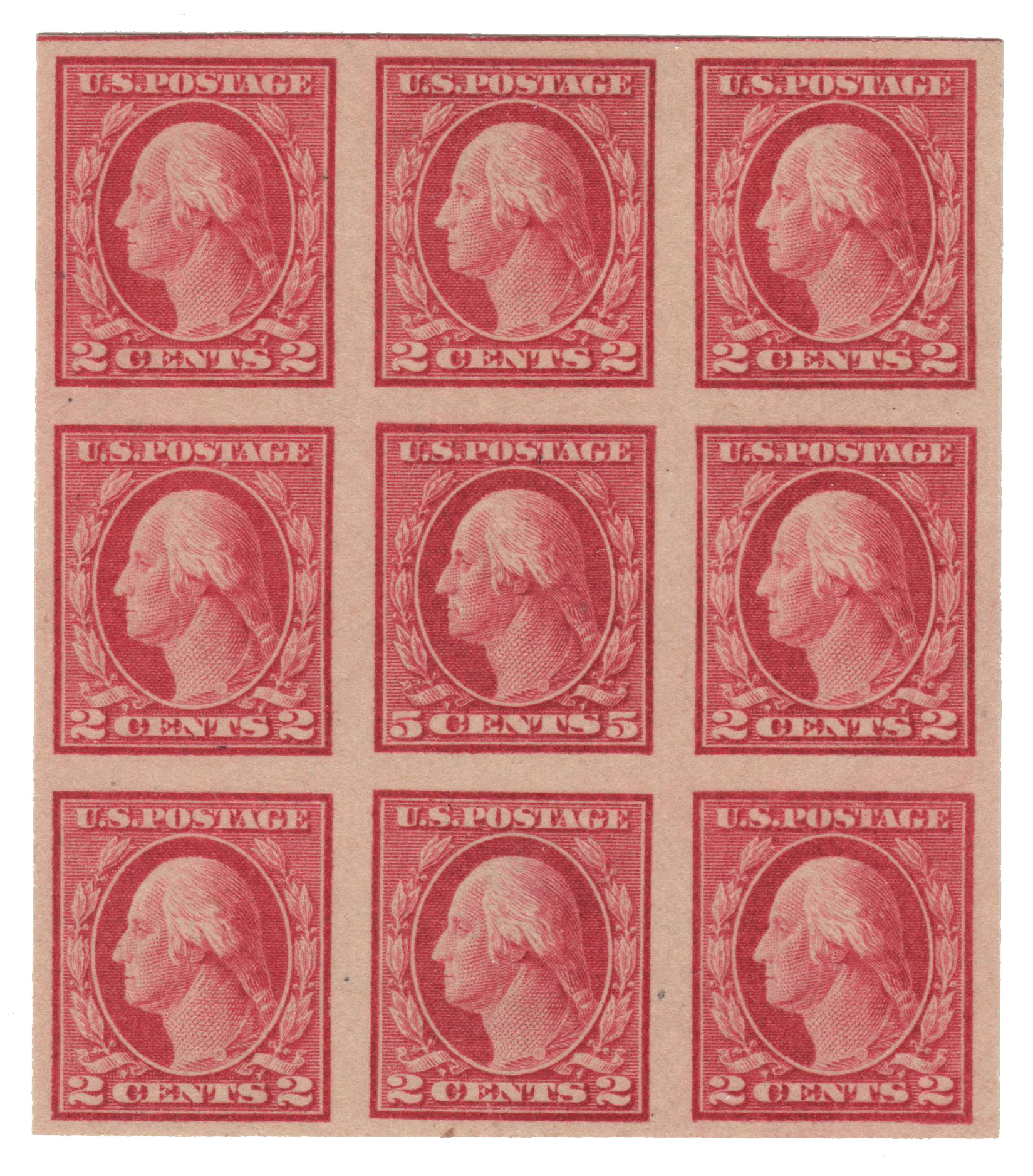

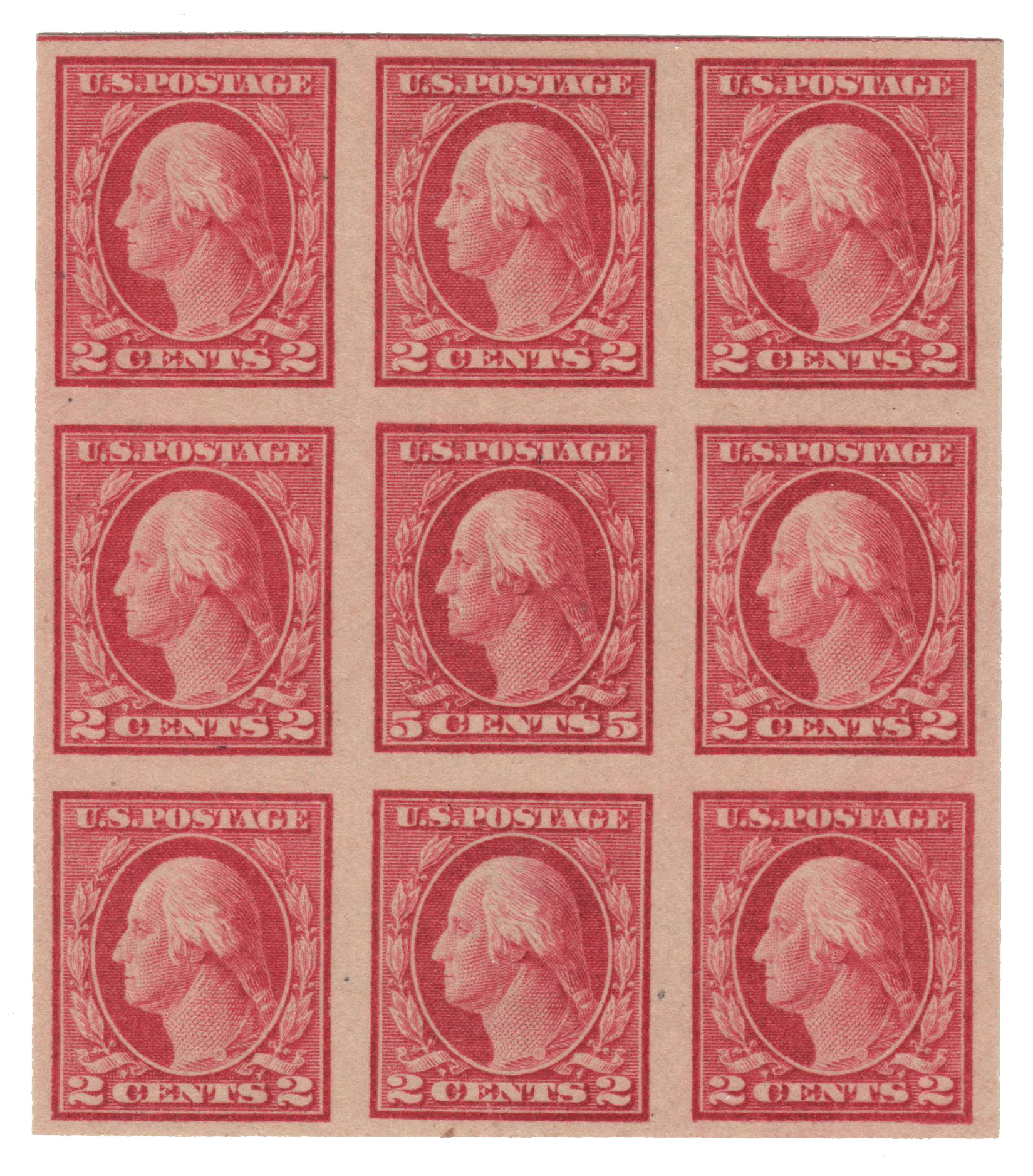

The new wartime rates meant the 3¢ stamp plates would be used more heavily than before. Operating at full capacity, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing found its ink to be of poor quality. Most of the high-quality ink came from Germany, and World War I interrupted the supply. The ink contained so much grit that printing plates wore out in about 10 days, faster than it took to make them. Therefor, the Bureau switched temporarily to offset printing, for which plates could be produced much more rapidly.

One of the negative aspects of using this method, however, was a less defined and somewhat blurry image. Some designs were modified in order to achieve a better impression. The lower quality of available ink combined with the deterioration of the Type I plates led to a decision that the plate dies would be cut deeper to prevent them from wearing out too quickly. This led to several different “types” of some stamps. These types have small differences in their engravings by which they can be identified. Later, a more satisfactory ink was found, and the higher quality engraving process used previously was re-established.

After the war ended the domestic letter rate was returned to 2¢ on June 30, 1919. The Victory stamp was the only 3¢ U.S. commemorative issued to pay the first-class letter rate during that period.

Over the course of the war, many countries depleted their resources. Items such as food, clothing, and machinery were greatly needed, and the US responded by sending shipments of supplies to the war-torn countries such as France and Russia. High-value stamps were needed to prepay postage and registry on international packages, and it was decided to release stamps with both $2 and $5 denominations. The sudden demand for these issues, however, did not allow time for new designs to be prepared. So, the designs from the 1902 series were used. Identical in color and design, the 1917 issues can be distinguished by their lack of a watermark.

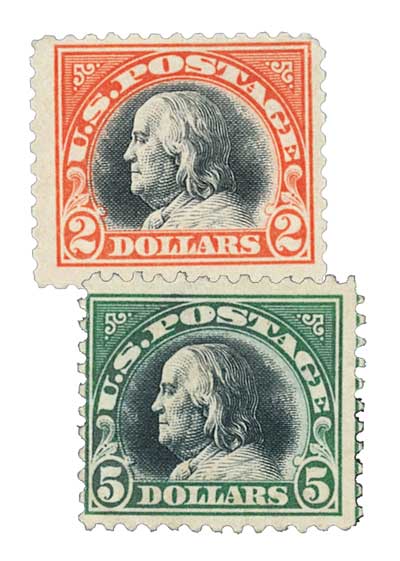

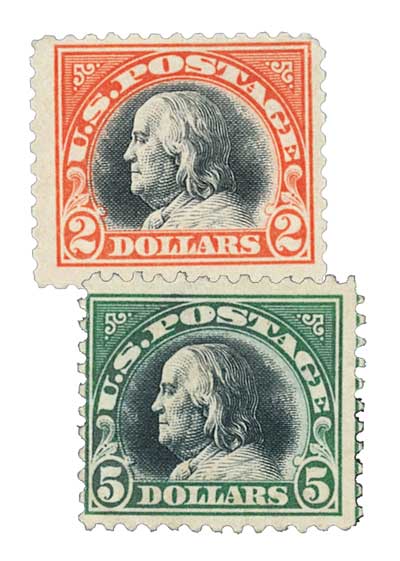

In 1918, the Bureau finally found the time to prepare new designs. On August 19th, the $2 and $5 stamps were released carrying portraits of Ben Franklin. In addition to being printed horizontally, they were also printed using two colors. The changes were made so postal clerks could easily tell the difference between these stamps and the lower denominations.

The $2 stamp was approved in dark red; however, due to an error, it was first printed in orange. Unfortunately, the error was not discovered until the stamps had been printed and distributed. When the Bureau received the proper ink, the stamps were printed in the intended color and redistributed. Collectors, however, not realizing the orange version was the error, stocked up on the dark red issue. Today, this error is extremely scarce. Although the shades of green on the $5 issue vary somewhat, they are all classified as deep green.

Are You Missing These 1916-17 Stamps?

Faced with Sudden Need, Printed with 1902 Master Dies

The US Postal Service was faced with a sudden and unexpected demand for high-denomination postage stamps early in 1917. The large numbers of heavy machine parts shipped to Russia required high postage amounts.

The Post Office did not have time to prepare new designs to meet the need, so the Series of 1902 master dies were used for the $2 Madison and $5 Marshall issues. The original plates and transfer rollers had already been destroyed.

The only differences between the 1902 and 1917 issues were that the earlier stamps were perf 12 and printed on double watermark paper. The 1917 issues were perf 10, on unwatermarked paper.

Both of these stamps were used to send valuable Liberty Bond shipments and #480 also paid for fund transfers between postal departments.

Mail During World War I

On November 2, 1917, the first class mail rate was raised from 2¢ to 3¢ to help cover the cost of the war effort.

Prior to this, the domestic letter rate for a one-ounce letter had been 2¢ since 1885. However, after the US entered World War I, the Post Office increased the rate to 3¢ on November 2, 1917. The extra 1¢ per ounce was charged as a war tax. The money raised by this tax was transferred to the Treasury’s general fund each month.

Prior to this change, 3¢ stamps saw little use. They didn’t satisfy any direct rate, but were sometimes used along with a 2¢ stamp to make up the 5¢ foreign letter rate or with the 10¢ denomination to pay foreign registration. This change greatly increased the demand for 3¢ stamps – and also for 1¢ stamps, to go with 2¢ stamps and stamped envelopes already purchased.

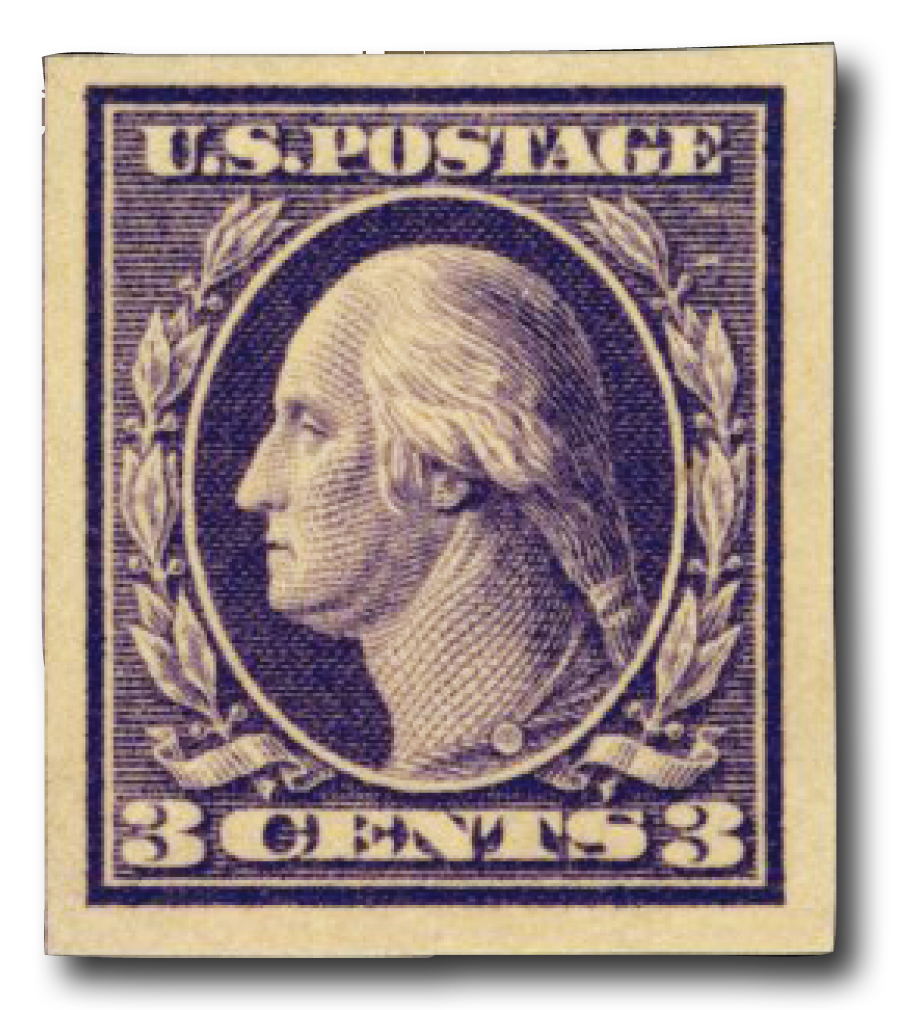

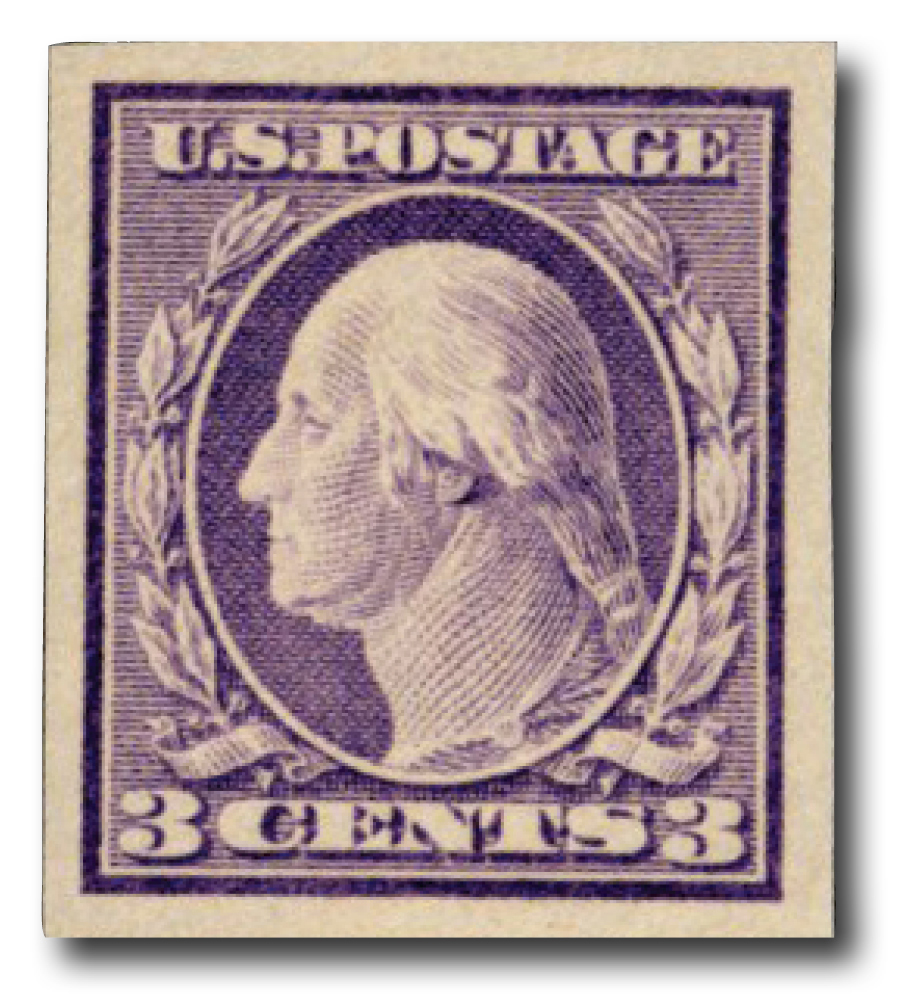

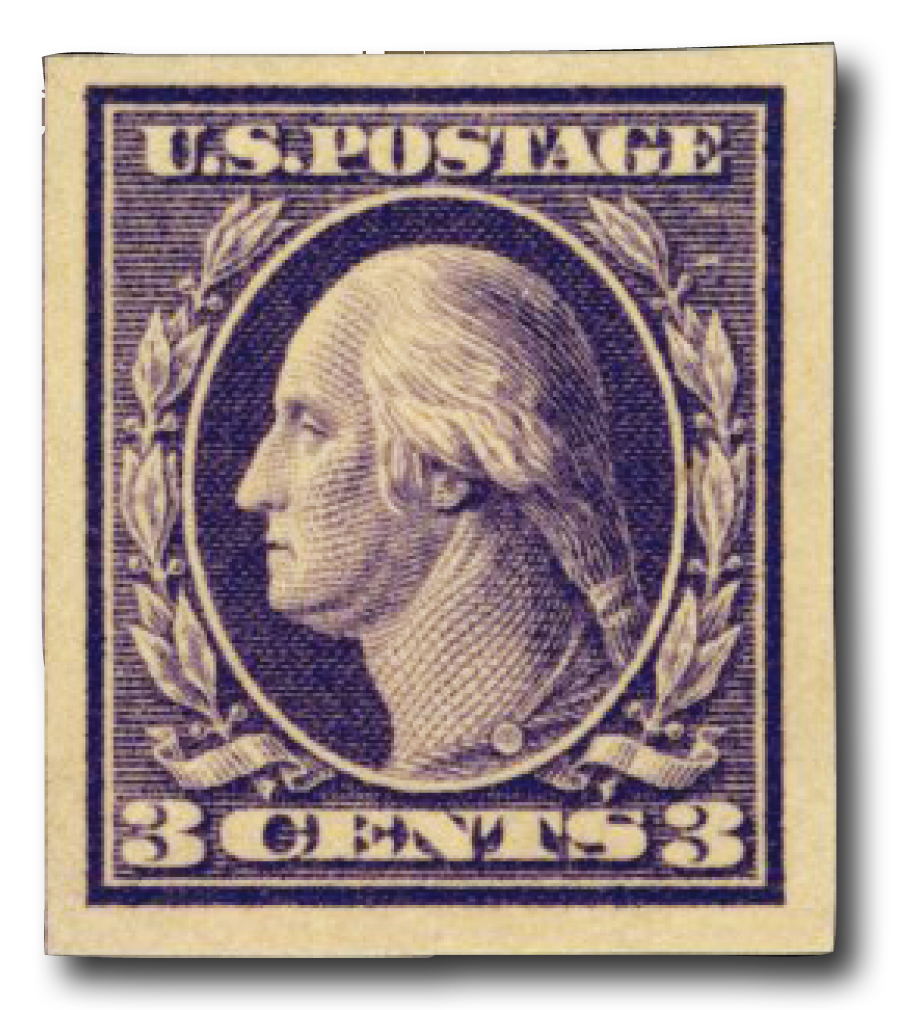

The new wartime rates meant the 3¢ stamp plates would be used more heavily than before. Operating at full capacity, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing found its ink to be of poor quality. Most of the high-quality ink came from Germany, and World War I interrupted the supply. The ink contained so much grit that printing plates wore out in about 10 days, faster than it took to make them. Therefor, the Bureau switched temporarily to offset printing, for which plates could be produced much more rapidly.

One of the negative aspects of using this method, however, was a less defined and somewhat blurry image. Some designs were modified in order to achieve a better impression. The lower quality of available ink combined with the deterioration of the Type I plates led to a decision that the plate dies would be cut deeper to prevent them from wearing out too quickly. This led to several different “types” of some stamps. These types have small differences in their engravings by which they can be identified. Later, a more satisfactory ink was found, and the higher quality engraving process used previously was re-established.

After the war ended the domestic letter rate was returned to 2¢ on June 30, 1919. The Victory stamp was the only 3¢ U.S. commemorative issued to pay the first-class letter rate during that period.

Over the course of the war, many countries depleted their resources. Items such as food, clothing, and machinery were greatly needed, and the US responded by sending shipments of supplies to the war-torn countries such as France and Russia. High-value stamps were needed to prepay postage and registry on international packages, and it was decided to release stamps with both $2 and $5 denominations. The sudden demand for these issues, however, did not allow time for new designs to be prepared. So, the designs from the 1902 series were used. Identical in color and design, the 1917 issues can be distinguished by their lack of a watermark.

In 1918, the Bureau finally found the time to prepare new designs. On August 19th, the $2 and $5 stamps were released carrying portraits of Ben Franklin. In addition to being printed horizontally, they were also printed using two colors. The changes were made so postal clerks could easily tell the difference between these stamps and the lower denominations.

The $2 stamp was approved in dark red; however, due to an error, it was first printed in orange. Unfortunately, the error was not discovered until the stamps had been printed and distributed. When the Bureau received the proper ink, the stamps were printed in the intended color and redistributed. Collectors, however, not realizing the orange version was the error, stocked up on the dark red issue. Today, this error is extremely scarce. Although the shades of green on the $5 issue vary somewhat, they are all classified as deep green.