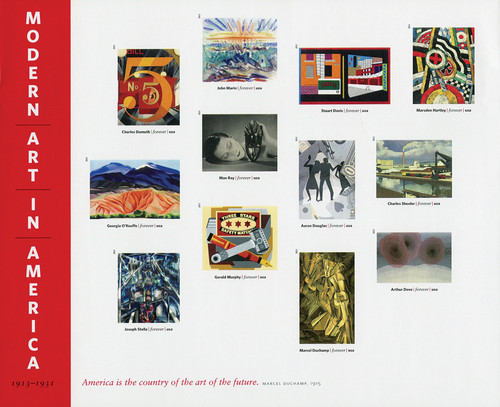

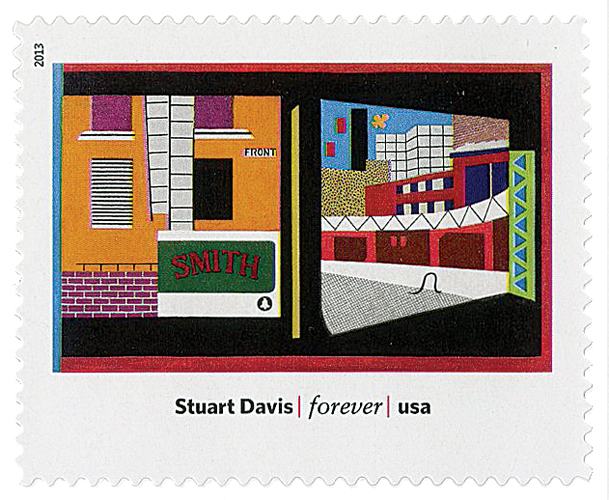

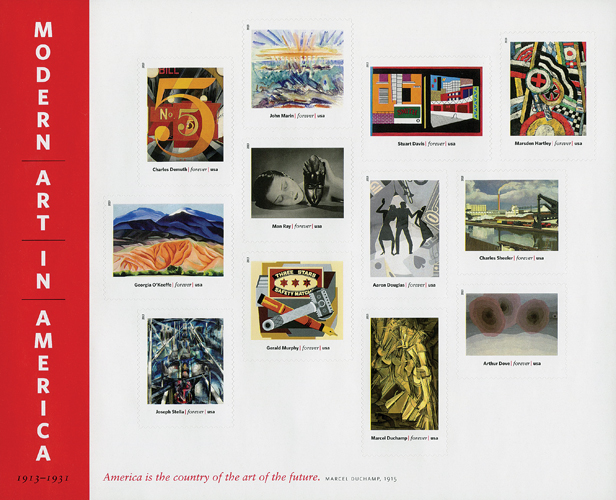

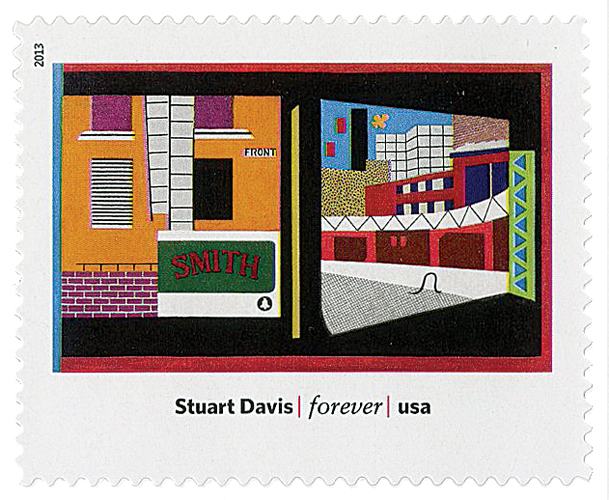

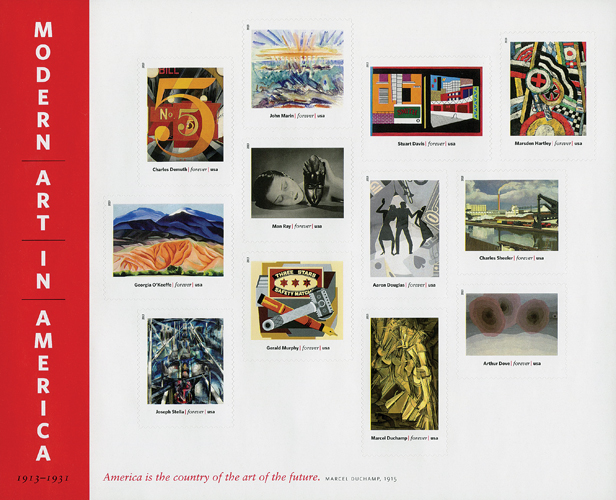

# 4748c - 2013 First-Class Forever Stamp - Modern Art in America: Stuart Davis' "House and Street"

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cuts 10 1/2

Color: multicolored

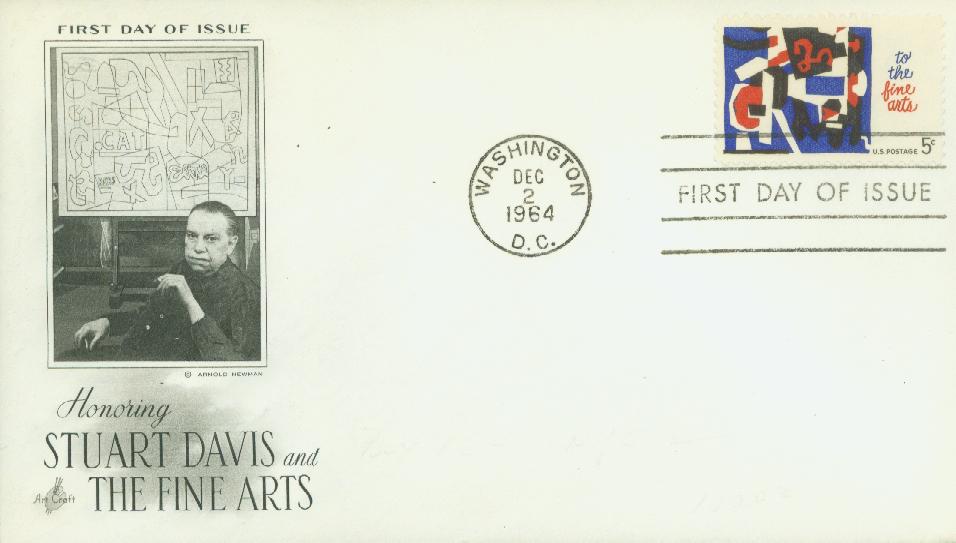

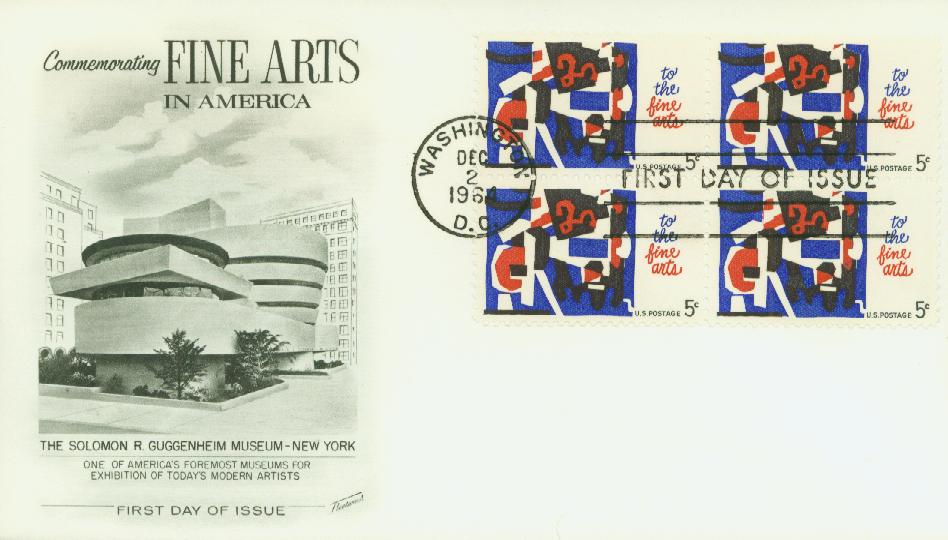

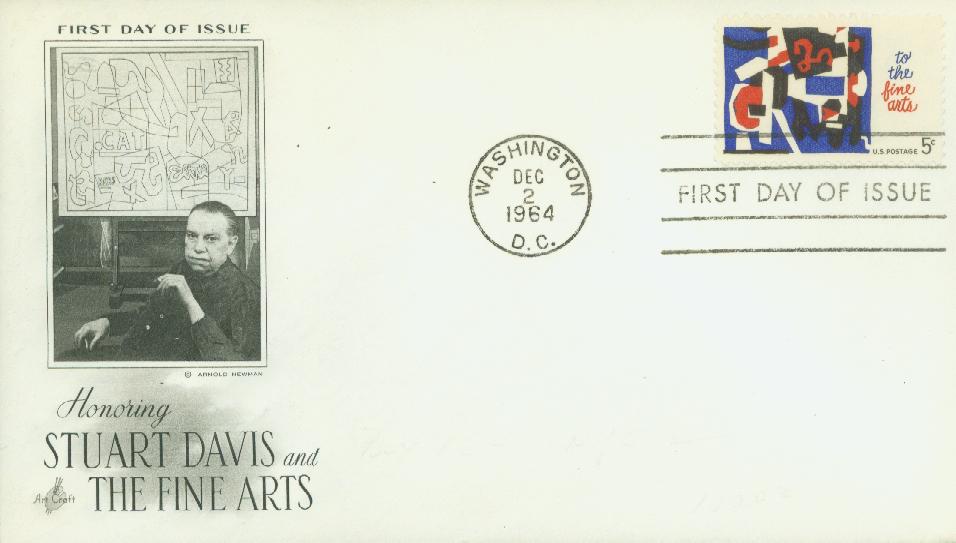

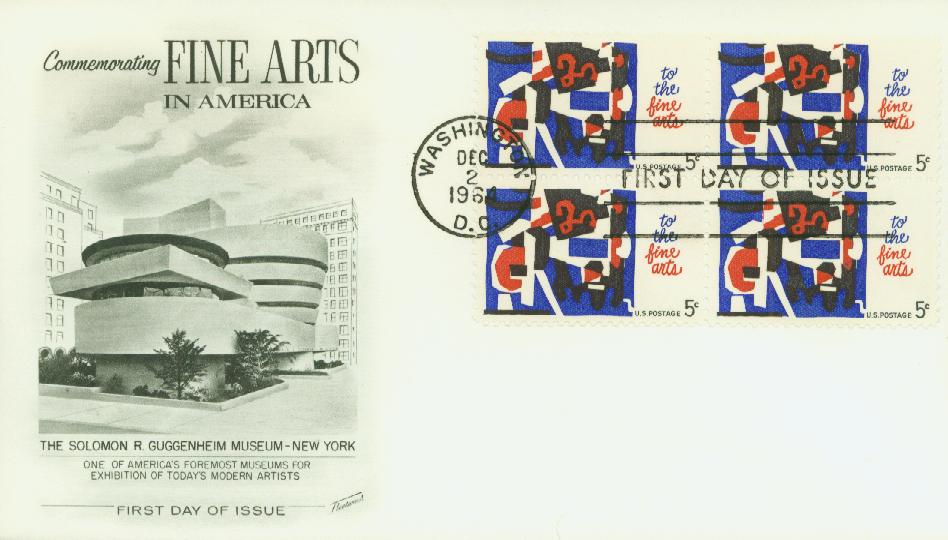

Death Of Stuart Davis

Stuart Davis was born on December 7, 1892, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The son of two artists, Stuart Davis was exposed to the creative world at an early age.

Davis began his formal art training in 1909, studying under Robert Henri from the Ashcan School (a form of realist art that pictured daily life in New York’s impoverished neighborhoods). One of the greatest lessons Davis received at this time was that “Art was not a matter of rules and techniques or the search for an absolute ideal of beauty. It was the expression of ideas and emotions about the life of the time.”

Then in 1913, Davis was one of the youngest artists to exhibit his work (five watercolor paintings) at the New York Armory Show. The Armory Show was one of the first large modern art exhibitions in the country and it exposed Davis to the works of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. After that show, Davis vowed to become a modern artist, abandoned his Realist training, and began to explore other subjects and styles.

Over the next few years, Davis spent his summers painting in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and made trips to Havana in 1918 and New Mexico in 1923. Davis was initially drafted into World War I but was instead allowed to work as a cartographer for the Army Intelligence Department. In the years since the Armory Show, Davis attempted to copy the styles he’d seen there. Then in 1919, he began to find his own signature style when he created his painting Self-Portrait. Throughout the 1920s, Davis began to focus on abstract still lifes and landscapes. He often painted everyday items such as cigarette packs and spark plug advertisements, which added an element of proto-pop art to his work.

The great crossroads of Davis’ career came in 1927 when he mounted an electric fan, rubber glove, and eggbeater to a table. He then painted the scene over and over, stripping his observations down to their most basic forms. The resulting four paintings earned him national fame. Soon, Davis was painting everything from street scenes to jazz clubs to soap boxes and gas pumps. He considered jazz to be the musical counterpart of abstract art, which had the feeling of the music’s beat and unusual rhythms.

With his increased fame, Davis was able to sell two paintings to fund a trip to Paris in 1928. There he was able to meet and talk to European modernists in person. Davis worked on a series of lithographs of cafes, streets, and alleys. He returned to New York the following year, but the Depression and death of his mentor, Robert Henri, were both major blows to the artist.

During the Depression, Davis grew much more political and attempted to “reconcile abstract Art with Marxism and modern industrial society,” according to art historian Cecile Whiting. Following the election of Franklin Roosevelt and his creation of New Deal programs, Davis became one of the first artists to apply for the Federal Art Project, for which he painted a series of murals.

In the 1930s, Davis began teaching at the Art Student’s League, followed by the New School for Social Research, and later at Yale. In the 1950s he twice represented the US at the Venice Biennale and he also received the Guggenheim International Award twice. In his later years, Davis’ Cubist-inspired paintings of everyday objects served as inspiration for another generation of painters in the Pop Art movement of the 1950s and 60s. Davis’s health declined in the 1960s and he died on June 24, 1964.

Click here to view some of Davis’ art.

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cuts 10 1/2

Color: multicolored

Death Of Stuart Davis

Stuart Davis was born on December 7, 1892, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The son of two artists, Stuart Davis was exposed to the creative world at an early age.

Davis began his formal art training in 1909, studying under Robert Henri from the Ashcan School (a form of realist art that pictured daily life in New York’s impoverished neighborhoods). One of the greatest lessons Davis received at this time was that “Art was not a matter of rules and techniques or the search for an absolute ideal of beauty. It was the expression of ideas and emotions about the life of the time.”

Then in 1913, Davis was one of the youngest artists to exhibit his work (five watercolor paintings) at the New York Armory Show. The Armory Show was one of the first large modern art exhibitions in the country and it exposed Davis to the works of Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso. After that show, Davis vowed to become a modern artist, abandoned his Realist training, and began to explore other subjects and styles.

Over the next few years, Davis spent his summers painting in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and made trips to Havana in 1918 and New Mexico in 1923. Davis was initially drafted into World War I but was instead allowed to work as a cartographer for the Army Intelligence Department. In the years since the Armory Show, Davis attempted to copy the styles he’d seen there. Then in 1919, he began to find his own signature style when he created his painting Self-Portrait. Throughout the 1920s, Davis began to focus on abstract still lifes and landscapes. He often painted everyday items such as cigarette packs and spark plug advertisements, which added an element of proto-pop art to his work.

The great crossroads of Davis’ career came in 1927 when he mounted an electric fan, rubber glove, and eggbeater to a table. He then painted the scene over and over, stripping his observations down to their most basic forms. The resulting four paintings earned him national fame. Soon, Davis was painting everything from street scenes to jazz clubs to soap boxes and gas pumps. He considered jazz to be the musical counterpart of abstract art, which had the feeling of the music’s beat and unusual rhythms.

With his increased fame, Davis was able to sell two paintings to fund a trip to Paris in 1928. There he was able to meet and talk to European modernists in person. Davis worked on a series of lithographs of cafes, streets, and alleys. He returned to New York the following year, but the Depression and death of his mentor, Robert Henri, were both major blows to the artist.

During the Depression, Davis grew much more political and attempted to “reconcile abstract Art with Marxism and modern industrial society,” according to art historian Cecile Whiting. Following the election of Franklin Roosevelt and his creation of New Deal programs, Davis became one of the first artists to apply for the Federal Art Project, for which he painted a series of murals.

In the 1930s, Davis began teaching at the Art Student’s League, followed by the New School for Social Research, and later at Yale. In the 1950s he twice represented the US at the Venice Biennale and he also received the Guggenheim International Award twice. In his later years, Davis’ Cubist-inspired paintings of everyday objects served as inspiration for another generation of painters in the Pop Art movement of the 1950s and 60s. Davis’s health declined in the 1960s and he died on June 24, 1964.

Click here to view some of Davis’ art.