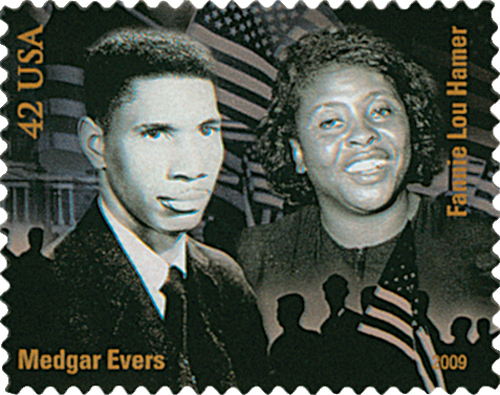

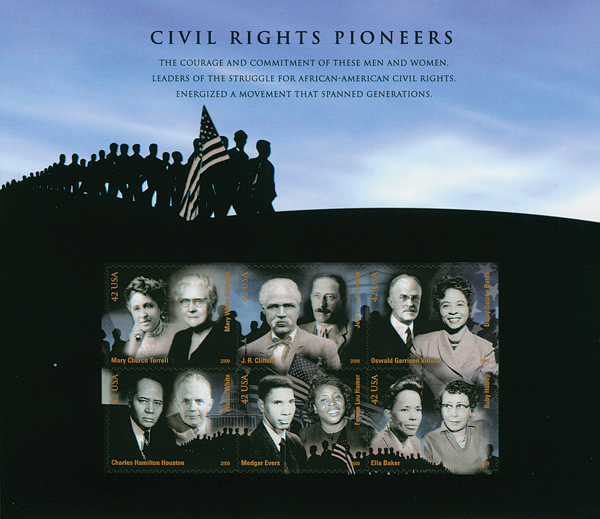

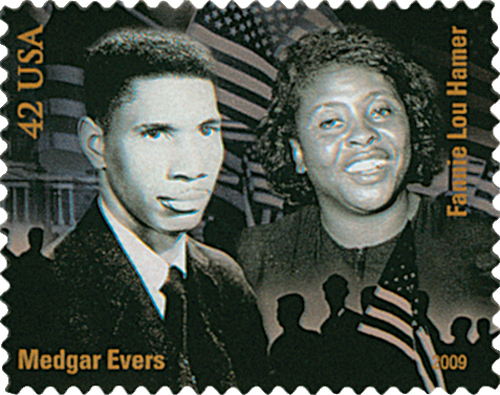

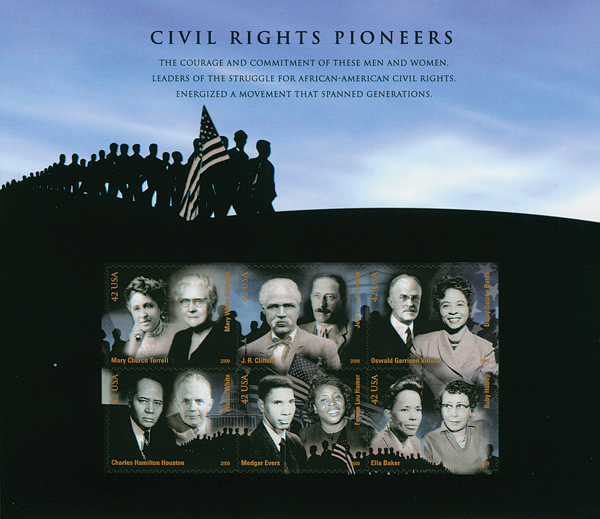

# 4384e - 2009 42c Civil Rights Pioneers: Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer

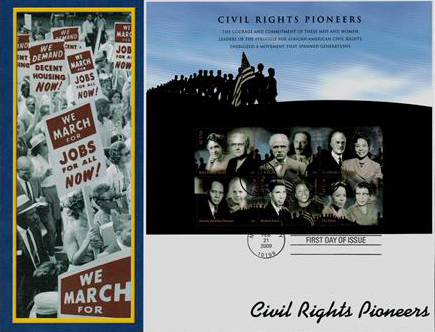

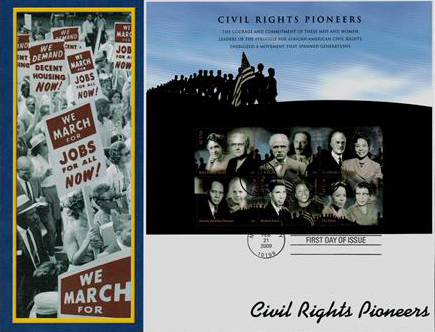

Civil Rights Pioneers

Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer

City: New York, NY

Color: Multicolored

The speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer electrified people engaged in the fight for equality in 1960s America. Granddaughter of slaves, Hamer rose above beatings, death threats, and imprisonment to co-found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Her work with the MFDP during “Freedom Summer” (1964) led to the recognition of black delegates, including herself, at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Believing civil rights concerns all races, Fannie Lou Hamer’s religious convictions fueled her struggle for freedom – a struggle reflected on her gravestone: “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Death Of Medgar Evers

On June 12, 1963, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was killed by a white supremacist while standing in his own driveway.

Medgar Wiley Evers was born on July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi. The third of five children, Evers walked 12 miles every day to attend a segregated school, where he eventually earned his high school diploma.

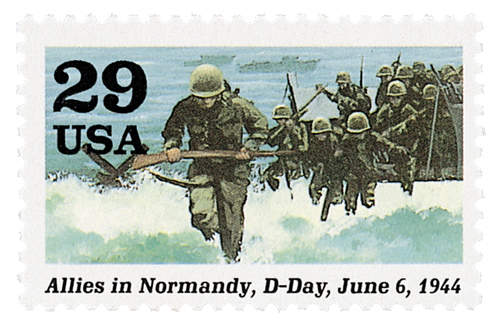

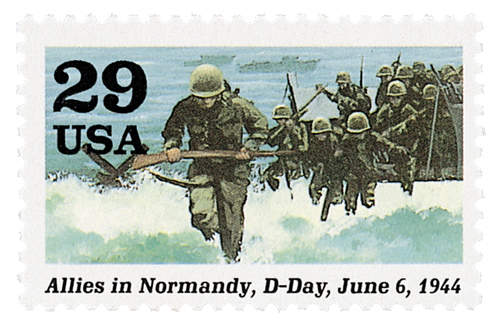

From 1943 to 1945, Evers served in the US Army during World War II. He fought in Germany and France, including the battle of Normandy. At the war’s end, he was honorably discharged as a sergeant.

In 1948, Evers entered Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, where he majored in business administration. While there he was part of the debate, football, and track teams, sang in the school choir, and was president of his junior class. He married classmate Myrlie Beasley in 1951 and graduated the following year.

After graduating, Evers and his wife moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi, where he found work as a salesman for Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. His employer was also the president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership and Evers helped lead the group’s boycott of gas stations that didn’t allow African Americans to use their restrooms.

After the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional, Evers applied to the state-supported University of Mississippi Law School. But he was denied because of his race. He had applied in part as a test case for the NAACP. In November of that year, he became the NAACP’s first field secretary for Mississippi. In that role, he organized boycotts, set up new chapters, and helped James Meredith become the first African American student admitted to the University of Mississippi.

Additionally, Evers encouraged the Biloxi wade-ins, protests against segregated public beaches. He also helped to integrate privately owned buses and parks and led boycotts to integrate Leake County schools and the Mississippi State Fair.

Evers had quickly become a major figure in the civil rights movement in Mississippi, which made him a target for white supremacists. On May 28, 1963, they threw a Molotov cocktail into his home carport and on June 7, he was almost run over by a car as he left the NAACP office. He had even trained his children what to do in case of a shooting or other attack on their home and was usually followed home by at least two FBI cars and one police car.

However, on the morning of June 12, 1963, neither the FBI nor local police escorted Evers home (it’s been suggested that many members of the police force were members of the Ku Klux Klan). After an early morning meeting with NAACP lawyers, Evers returned home but was shot after getting out of his car. His wife took him to the local hospital, where he was initially refused care because of his race. He was eventually admitted but died 50 minutes later at the age of just 37. He was the first African American admitted to an all-white hospital in Mississippi.

A World War II veteran, Evers was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on June 19. More than 3,000 people attended to pay their respects. A group of 5,000 people led by Allen Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr. led a march from the Masonic Temple to the funeral home.

Evers’ assassin, Byron De La Beckwith, was arrested on June 21, however, two trials before all-white juries failed to reach a verdict. Evers’ wife continued to push for justice and in 1994, De La Beckwith was sentenced to life in prison.

Civil Rights Pioneers

Medgar Evers and Fannie Lou Hamer

City: New York, NY

Color: Multicolored

The speeches of Fannie Lou Hamer electrified people engaged in the fight for equality in 1960s America. Granddaughter of slaves, Hamer rose above beatings, death threats, and imprisonment to co-found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. Her work with the MFDP during “Freedom Summer” (1964) led to the recognition of black delegates, including herself, at the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Believing civil rights concerns all races, Fannie Lou Hamer’s religious convictions fueled her struggle for freedom – a struggle reflected on her gravestone: “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Death Of Medgar Evers

On June 12, 1963, civil rights activist Medgar Evers was killed by a white supremacist while standing in his own driveway.

Medgar Wiley Evers was born on July 2, 1925, in Decatur, Mississippi. The third of five children, Evers walked 12 miles every day to attend a segregated school, where he eventually earned his high school diploma.

From 1943 to 1945, Evers served in the US Army during World War II. He fought in Germany and France, including the battle of Normandy. At the war’s end, he was honorably discharged as a sergeant.

In 1948, Evers entered Alcorn Agricultural and Mechanical College, where he majored in business administration. While there he was part of the debate, football, and track teams, sang in the school choir, and was president of his junior class. He married classmate Myrlie Beasley in 1951 and graduated the following year.

After graduating, Evers and his wife moved to Mound Bayou, Mississippi, where he found work as a salesman for Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. His employer was also the president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership and Evers helped lead the group’s boycott of gas stations that didn’t allow African Americans to use their restrooms.

After the 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregated schools were unconstitutional, Evers applied to the state-supported University of Mississippi Law School. But he was denied because of his race. He had applied in part as a test case for the NAACP. In November of that year, he became the NAACP’s first field secretary for Mississippi. In that role, he organized boycotts, set up new chapters, and helped James Meredith become the first African American student admitted to the University of Mississippi.

Additionally, Evers encouraged the Biloxi wade-ins, protests against segregated public beaches. He also helped to integrate privately owned buses and parks and led boycotts to integrate Leake County schools and the Mississippi State Fair.

Evers had quickly become a major figure in the civil rights movement in Mississippi, which made him a target for white supremacists. On May 28, 1963, they threw a Molotov cocktail into his home carport and on June 7, he was almost run over by a car as he left the NAACP office. He had even trained his children what to do in case of a shooting or other attack on their home and was usually followed home by at least two FBI cars and one police car.

However, on the morning of June 12, 1963, neither the FBI nor local police escorted Evers home (it’s been suggested that many members of the police force were members of the Ku Klux Klan). After an early morning meeting with NAACP lawyers, Evers returned home but was shot after getting out of his car. His wife took him to the local hospital, where he was initially refused care because of his race. He was eventually admitted but died 50 minutes later at the age of just 37. He was the first African American admitted to an all-white hospital in Mississippi.

A World War II veteran, Evers was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on June 19. More than 3,000 people attended to pay their respects. A group of 5,000 people led by Allen Johnson and Martin Luther King Jr. led a march from the Masonic Temple to the funeral home.

Evers’ assassin, Byron De La Beckwith, was arrested on June 21, however, two trials before all-white juries failed to reach a verdict. Evers’ wife continued to push for justice and in 1994, De La Beckwith was sentenced to life in prison.