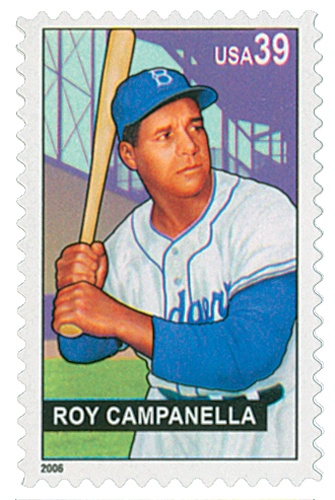

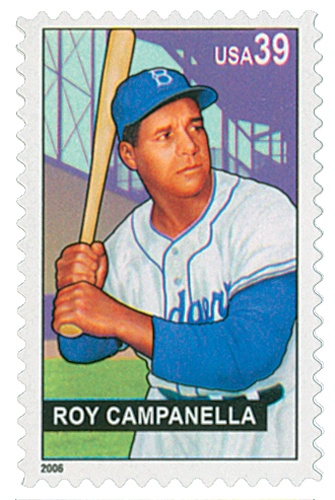

# 4080 - 2006 39c Baseball Sluggers: Roy Campanella

U.S. #4080

Baseball Sluggers

Roy Campanella

City: Bronx, NY

Quantity: 200,000,000

Printed by: Avery Dennison

Printing method: Photogravure

Perforations: Die cut 10 ¾

Color: Multicolored

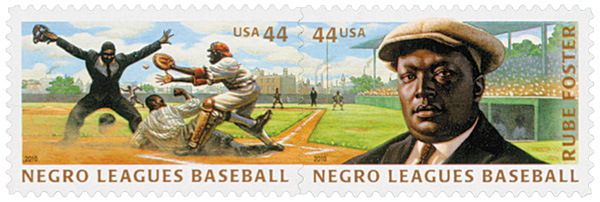

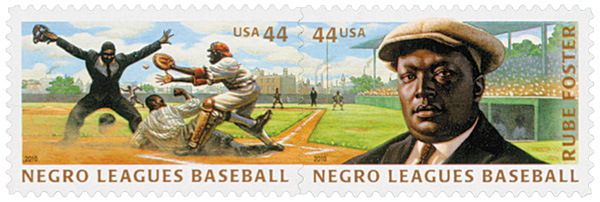

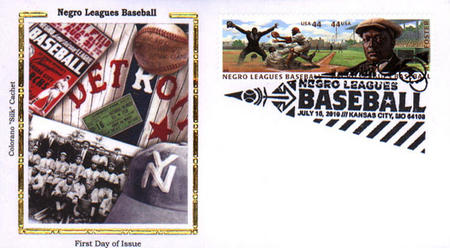

First Game Of Negro National League Baseball

On May 2, 1920, the first game of the Negro National Baseball League was played in Indianapolis, Indiana.

In the late 1800s, baseball was divided by a color line. A rule known as the “Gentleman’s Agreement” banned black players from white leagues. From behind this color line, a new American pastime was born – Negro Leagues Baseball.

In 1920, Rube Foster met with several other Negro baseball team owners at the YMCA in Kansas City. When the meeting concluded, Foster introduced the Negro National League by proclaiming, “We are the ship, all else the sea.”

Foster said his goal for forming a Negro League was “to create a profession that would equal the earning capacity of any other profession… and do something concrete for the loyalty of the Race.” Foster backed that up by paying his players a minimum salary of $175 a month – at a time when the average monthly salary in America was $103.

Foster would work 15-hour days to keep the league running. To ensure payrolls were met on time, Rube advanced loans to other owners out of his own pocket. He also shifted players within the league to ensure equal competition between teams. Foster wanted black players to be ready when integration finally came. He routinely spoke to players, telling them to always play at the highest level of excellence.

The first game of this new league was held on May 2, 1920, in Indiana. It was between Foster’s team, the American Giants, and the Indianapolis ABCs. The ABCs went on to win that game 4 to 2, though the Giants would eventually win that year’s championship.

Soon, fans flocked to the ballparks and were treated to a fast-paced game filled with action and flamboyance. Players like Satchel Paige electrified the crowds with their showmanship. A tall, lanky right-hander, Paige often told the outfielders to sit down while he struck out the next batter. And “Cool Papa” Bell would often try to steal two bases on one pitch.

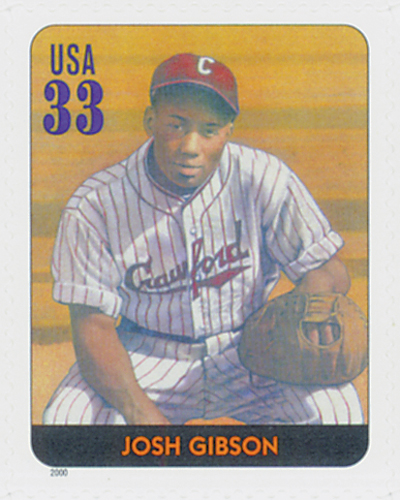

Another great was Josh Gibson. Referred to as the “black Babe Ruth,” Gibson belted home runs that traveled more than 575 feet. And Oscar Charleston, dubbed the “black Ty Cobb,” was always a threat to steal a base or run down a long fly ball. This amazing talent made baseball the favorite pastime for black Americans.

Behind all the pageantry, life in Negro baseball was tough. When the team bus stopped at a restaurant, the players weren’t allowed in the dining room. And they often slept on the buses because white hotels wouldn’t rent them rooms. “We didn’t get a chance sometimes to take a bath for 3 or 4 days because they wouldn’t let us,” recalled Ted Radcliffe.

By the 1940s, the ballpark became a place for community gatherings. Negro Leagues baseball was the largest black-owned organization in America, and the league did its part to aid a community living with segregation. Owners raised money to support anti-lynching campaigns, the United Negro College Fund, and the NAACP.

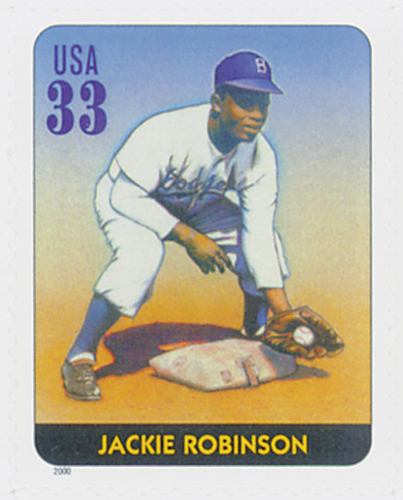

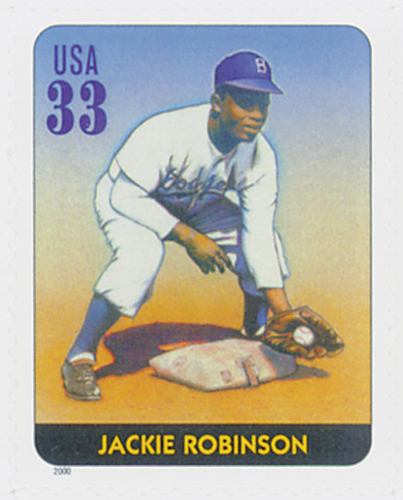

In 1947, the color barrier was broken when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. Within five years, more than 150 Negro Leagues players joined Major League teams. Without its greatest stars, and struggling with low attendance, the era of Negro Leagues baseball came to a close.

Click here for a brief video about the Negro League.

U.S. #4080

Baseball Sluggers

Roy Campanella

City: Bronx, NY

Quantity: 200,000,000

Printed by: Avery Dennison

Printing method: Photogravure

Perforations: Die cut 10 ¾

Color: Multicolored

First Game Of Negro National League Baseball

On May 2, 1920, the first game of the Negro National Baseball League was played in Indianapolis, Indiana.

In the late 1800s, baseball was divided by a color line. A rule known as the “Gentleman’s Agreement” banned black players from white leagues. From behind this color line, a new American pastime was born – Negro Leagues Baseball.

In 1920, Rube Foster met with several other Negro baseball team owners at the YMCA in Kansas City. When the meeting concluded, Foster introduced the Negro National League by proclaiming, “We are the ship, all else the sea.”

Foster said his goal for forming a Negro League was “to create a profession that would equal the earning capacity of any other profession… and do something concrete for the loyalty of the Race.” Foster backed that up by paying his players a minimum salary of $175 a month – at a time when the average monthly salary in America was $103.

Foster would work 15-hour days to keep the league running. To ensure payrolls were met on time, Rube advanced loans to other owners out of his own pocket. He also shifted players within the league to ensure equal competition between teams. Foster wanted black players to be ready when integration finally came. He routinely spoke to players, telling them to always play at the highest level of excellence.

The first game of this new league was held on May 2, 1920, in Indiana. It was between Foster’s team, the American Giants, and the Indianapolis ABCs. The ABCs went on to win that game 4 to 2, though the Giants would eventually win that year’s championship.

Soon, fans flocked to the ballparks and were treated to a fast-paced game filled with action and flamboyance. Players like Satchel Paige electrified the crowds with their showmanship. A tall, lanky right-hander, Paige often told the outfielders to sit down while he struck out the next batter. And “Cool Papa” Bell would often try to steal two bases on one pitch.

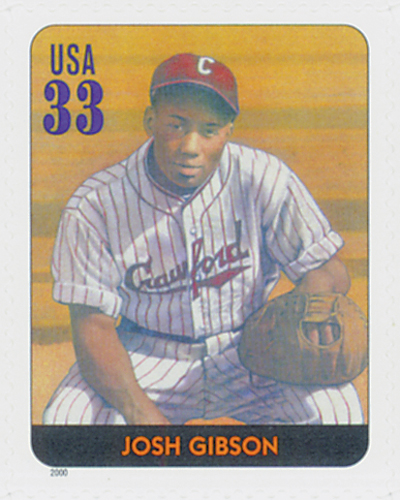

Another great was Josh Gibson. Referred to as the “black Babe Ruth,” Gibson belted home runs that traveled more than 575 feet. And Oscar Charleston, dubbed the “black Ty Cobb,” was always a threat to steal a base or run down a long fly ball. This amazing talent made baseball the favorite pastime for black Americans.

Behind all the pageantry, life in Negro baseball was tough. When the team bus stopped at a restaurant, the players weren’t allowed in the dining room. And they often slept on the buses because white hotels wouldn’t rent them rooms. “We didn’t get a chance sometimes to take a bath for 3 or 4 days because they wouldn’t let us,” recalled Ted Radcliffe.

By the 1940s, the ballpark became a place for community gatherings. Negro Leagues baseball was the largest black-owned organization in America, and the league did its part to aid a community living with segregation. Owners raised money to support anti-lynching campaigns, the United Negro College Fund, and the NAACP.

In 1947, the color barrier was broken when Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers. Within five years, more than 150 Negro Leagues players joined Major League teams. Without its greatest stars, and struggling with low attendance, the era of Negro Leagues baseball came to a close.

Click here for a brief video about the Negro League.