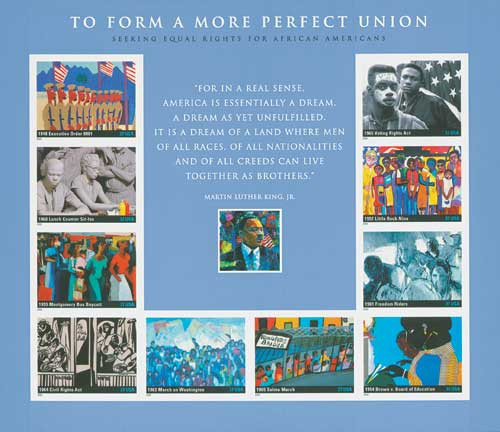

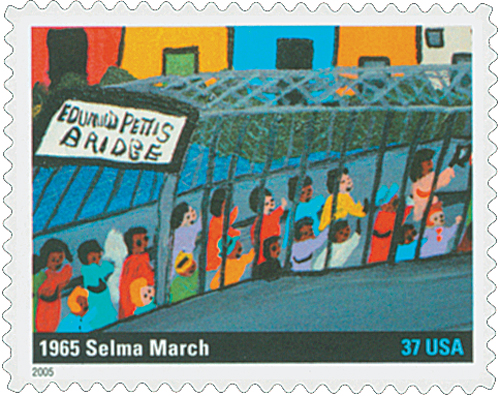

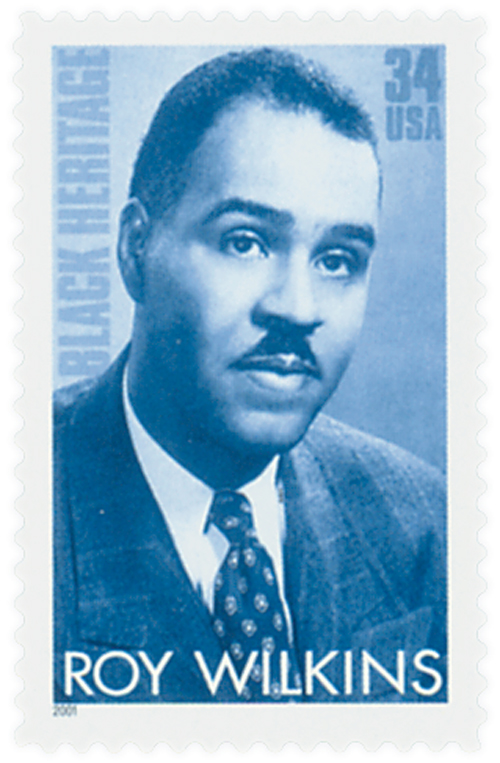

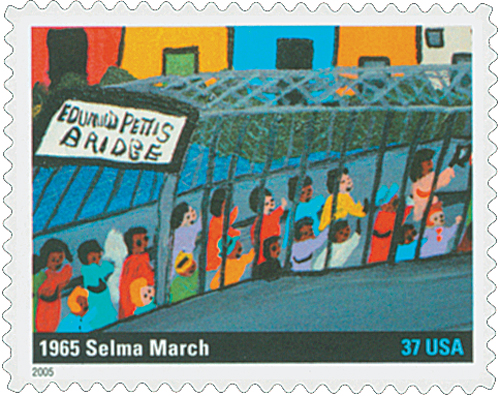

# 3937i - 2005 37c To Form a More Perfect Union: Selma March

37¢ 1965 Selma March

To Form a More Perfect Union

City: Washington, DC

Printing Method: Lithographed

Color: Multicolored

Final Selma March Begins

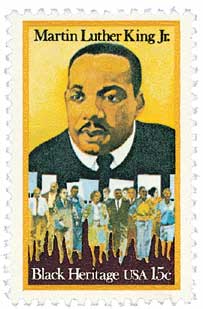

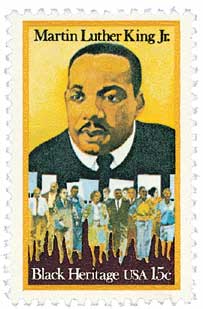

On March 21, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led the third (and finally successful) march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest for voting rights.

The 15th and 19th Amendments to the United States Constitution granted black citizens the right to vote. However, Southern registration boards used poll taxes, literacy tests, and other strategies to deny this right.

The murder of voting-rights activists in Mississippi in 1964 brought national attention to the issue. In 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) traveled to Selma, Alabama, to fight for black citizens’ right to vote.

The SCLC demonstrations led to the mass arrests of hundreds of protesting students. For days, news media showed black children being led to jail. During one protest, police fatally shot a black veteran who was protecting his mother. After his death, the idea grew for a procession to the state capital.

The first Selma March began on February 1, 1965, and resulted in the arrests of 770 participants. Then, on Sunday, March 7, 1965, Selma residents and supporters attempted a second march. As they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, police stopped them, told them to disperse, then fired tear gas and beat the protesters. Scenes of club-wielding police beating marchers were broadcast around the world. Two days later, Martin Luther King, Jr. led 1,500 protesters, but turned back to avoid a confrontation with troopers.

King planned another march with people from all over the country. A court order limited the marchers to the bridge. James Reeb, a white minister from Boston, was beaten to death following the march. A week later, with the restraining order lifted, the full march was scheduled for March 21.

In the meantime, President Lyndon Johnson offered his support, lobbying for passage of the new voting rights act he was introducing to Congress. He also ordered U.S. Army, National Guard, federal marshals, and FBI agents to Selma to protect the marchers. As planned, about 2,000 people left Selma on March 21. Over the next four days, they traveled 54 miles, walking up to 12 hours each day and slept in fields at night. On March 25 they reached Montgomery, where they were greeted by 50,000 supporters in front of the state capital.

King addressed the crowd and people watching the event on television. “They told us we wouldn’t get here. And there were those who said that we would get here only over their dead bodies, but all the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power in the state of Alabama saying, ‘We ain’t goin’ let nobody turn us around.’” Others took the podium to thank the marchers for their dedication. Among them was Nobel Peace Prize winner Ralph Bunche, who said, “I earnestly salute every one of you for expressing by your presence here the finest in the American tradition; you are in truth the modern day ‘Minute Men’ of the American national conscience. You have written a great new chapter in the heroic history of American freedom.”

Three months later, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act prohibited individual state restrictions that made it difficult – or impossible – for blacks to vote. The Act was passed by large majorities in both houses of Congress and signed into law on August 6. Within months of its passage, a quarter of a million new black voters had registered. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, barely 100 African-Americans held any elective office in the U.S.; by 1989, there were more than 7,200. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 accomplished its purpose.

Click here to read and listen to King’s March 25th speech in Montgomery. And click here to read to Ralph Bunche’s speech.

37¢ 1965 Selma March

To Form a More Perfect Union

City: Washington, DC

Printing Method: Lithographed

Color: Multicolored

Final Selma March Begins

On March 21, 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. led the third (and finally successful) march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, to protest for voting rights.

The 15th and 19th Amendments to the United States Constitution granted black citizens the right to vote. However, Southern registration boards used poll taxes, literacy tests, and other strategies to deny this right.

The murder of voting-rights activists in Mississippi in 1964 brought national attention to the issue. In 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) traveled to Selma, Alabama, to fight for black citizens’ right to vote.

The SCLC demonstrations led to the mass arrests of hundreds of protesting students. For days, news media showed black children being led to jail. During one protest, police fatally shot a black veteran who was protecting his mother. After his death, the idea grew for a procession to the state capital.

The first Selma March began on February 1, 1965, and resulted in the arrests of 770 participants. Then, on Sunday, March 7, 1965, Selma residents and supporters attempted a second march. As they tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, police stopped them, told them to disperse, then fired tear gas and beat the protesters. Scenes of club-wielding police beating marchers were broadcast around the world. Two days later, Martin Luther King, Jr. led 1,500 protesters, but turned back to avoid a confrontation with troopers.

King planned another march with people from all over the country. A court order limited the marchers to the bridge. James Reeb, a white minister from Boston, was beaten to death following the march. A week later, with the restraining order lifted, the full march was scheduled for March 21.

In the meantime, President Lyndon Johnson offered his support, lobbying for passage of the new voting rights act he was introducing to Congress. He also ordered U.S. Army, National Guard, federal marshals, and FBI agents to Selma to protect the marchers. As planned, about 2,000 people left Selma on March 21. Over the next four days, they traveled 54 miles, walking up to 12 hours each day and slept in fields at night. On March 25 they reached Montgomery, where they were greeted by 50,000 supporters in front of the state capital.

King addressed the crowd and people watching the event on television. “They told us we wouldn’t get here. And there were those who said that we would get here only over their dead bodies, but all the world today knows that we are here and we are standing before the forces of power in the state of Alabama saying, ‘We ain’t goin’ let nobody turn us around.’” Others took the podium to thank the marchers for their dedication. Among them was Nobel Peace Prize winner Ralph Bunche, who said, “I earnestly salute every one of you for expressing by your presence here the finest in the American tradition; you are in truth the modern day ‘Minute Men’ of the American national conscience. You have written a great new chapter in the heroic history of American freedom.”

Three months later, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The act prohibited individual state restrictions that made it difficult – or impossible – for blacks to vote. The Act was passed by large majorities in both houses of Congress and signed into law on August 6. Within months of its passage, a quarter of a million new black voters had registered. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, barely 100 African-Americans held any elective office in the U.S.; by 1989, there were more than 7,200. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 accomplished its purpose.

Click here to read and listen to King’s March 25th speech in Montgomery. And click here to read to Ralph Bunche’s speech.