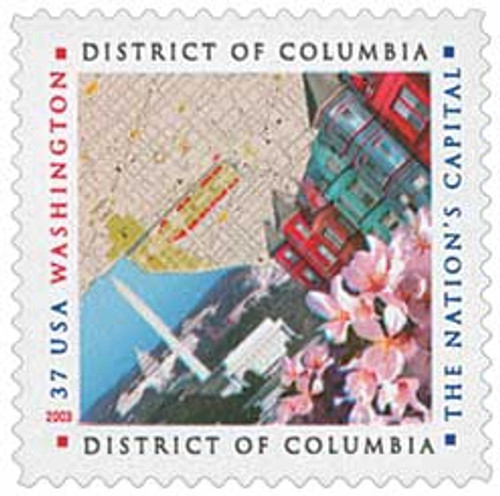

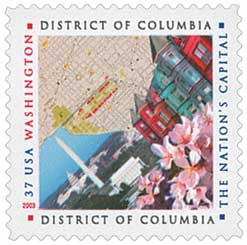

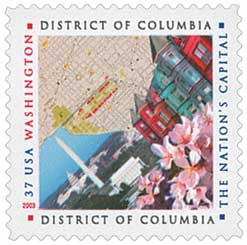

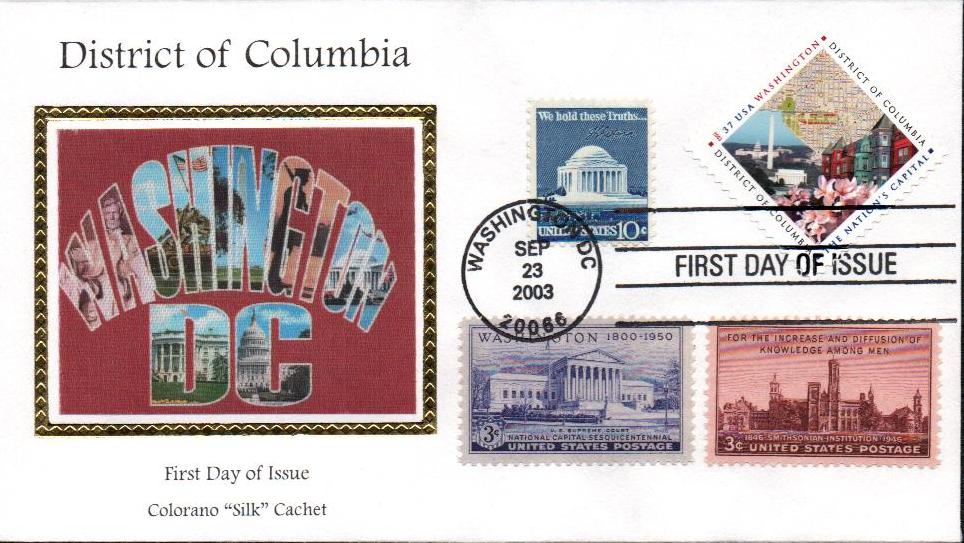

# 3813 - 2003 37c District of Columbia

37¢ District of Columbia

City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity: 72,000,000

Printed By: American Packaging Corporation for Sennett Security Products

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cut 11

Color: Multicolored

District Of Columbia

On July 16, 1790, the District of Columbia was established with George Washington’s signing of the Residence Act.

Philadelphia was America’s first capital city starting in 1774. However, in 1783, an angry group of soldiers went to Independence Hall demanding payment for their service during the American Revolution. When Pennsylvania governor John Dickinson refused to remove them, Congress fled to Princeton, New Jersey.

Four years later, the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention granted Congress the power “To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding 10 miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of government of the United States.”

James Madison added that the national capital should be separate from the rest of the states, being responsible for its own maintenance and security. Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia all offered territory for the capital. Eventually, Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton selected the area around the Potomac River to serve as the national capital.

By 1789, Maryland and Virginia ceded a combined 100 square miles to serve as the capital. On July 9, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, approving the creation of the national capital on the Potomac River. Days later, President George Washington selected the exact location of the new capital. He then signed the Residence Act on July 16, officially establishing America’s new permanent capital.

In 1791, Washington appointed three commissioners to oversee the planning, design, and creation of property. A major part of this was the naming of the new capital. During the American Revolution, colonists viewed Christopher Columbus as a hero of their nation. They adopted the Roman Goddess of liberty and freedom as their symbol and named her Columbia after Columbus. The commission ultimately named the Federal District “The Territory of Columbia,” and the Federal City “The City of Washington.”

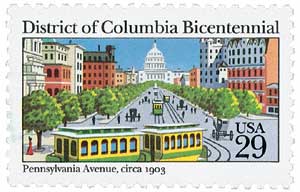

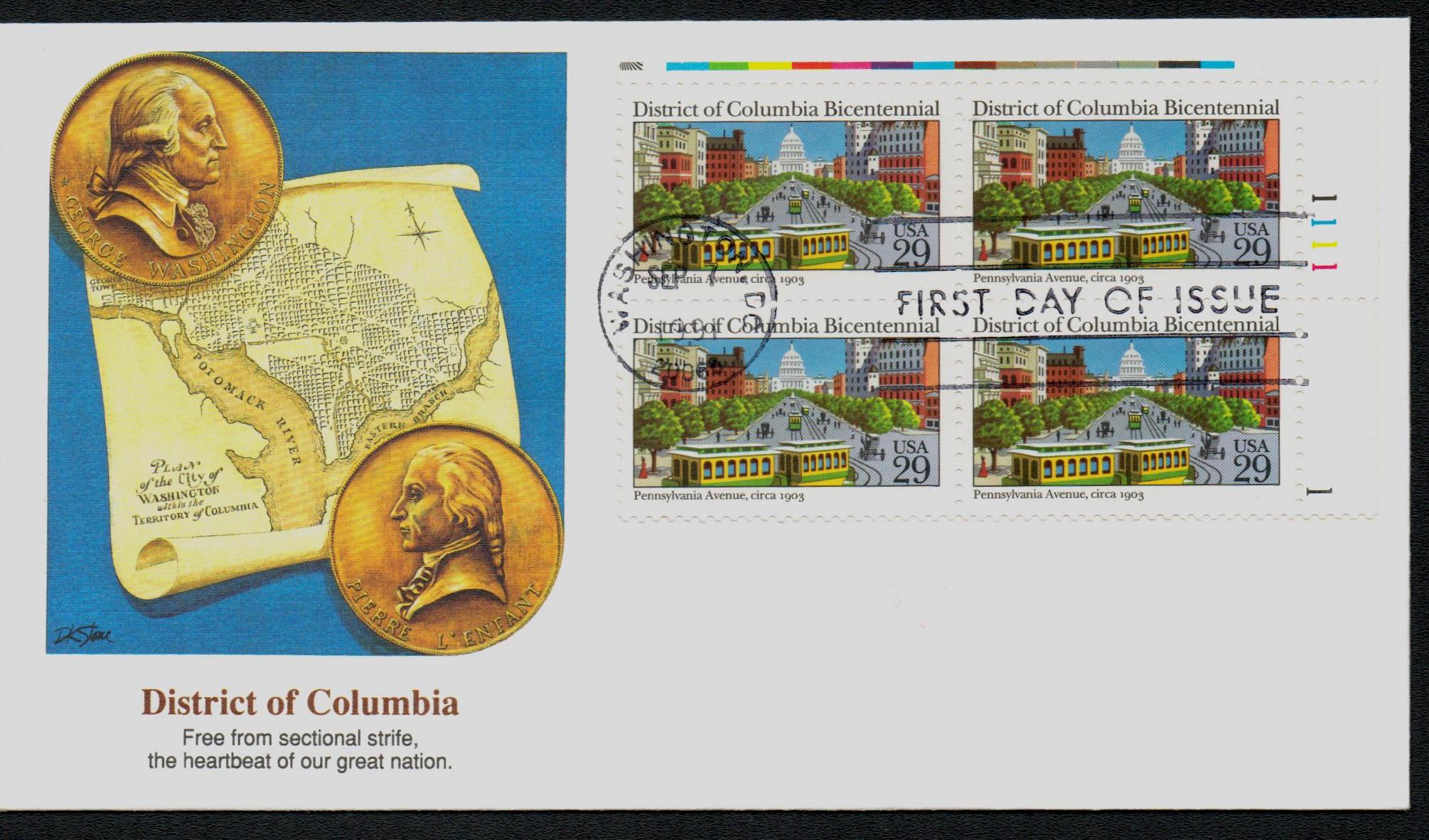

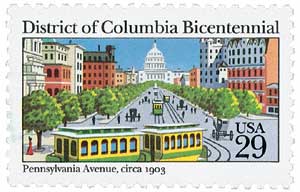

Around this time, President Washington hired Pierre Charles L’Enfant to design the capital city at the center of the federal territory. L’Enfant’s plan revolved around the US Capitol Building on top of Jenkins Hill with wide diagonal avenues crossing the city’s layout. He also designed the narrow Pennsylvania Avenue to connect the Capitol Building and White House. After L’Enfant became involved in several conflicts with the city’s commissioners and refused to provide planners with an engraved city plan, he was let go. Andrew Ellicott made several changes to L’Enfant’s plan and had it engraved, making it the first distributed plan of the city.

In 1800, the national government was officially moved to the new city. The following year, the federal district and the municipalities of Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria were placed under the control of Congress. In 1802, the City of Washington was granted a territorial government led by a President-appointed mayor. Congress was made responsible for capital improvements and economic development initiatives, but did not have loyalty to the city and often provided little or no support.

In 1846, 39 square miles were returned to Virginia and part of that land later became the Arlington National Cemetery. The capital continued to function during the Civil War and the government grew significantly to oversee the war and was partially responsible for the large increase in the city’s population. Under Robey Shepherd’s governorship in the 1870s, several improvements were introduced, including paved streets and a new sewer system. However, his excessive spending caused Congress to remove the position of governor and take over its control, which lasted for more than 100 years.

At the beginning of the 1900s, the District formed the McMillan Plan, intended to carry out L’Enfant’s unfinished vision of the city. This included removing poor neighborhoods and replacing them with public monuments, government buildings, and new, modern, affordable homes.

Throughout the 20th Century, the nation’s capital was often at the center of civil rights issues. In March 1961, the people of Washington, DC, were finally given the right to choose electors for President and Vice President. And in 1973, Congress granted the district a directly elected city council and mayor. Five years later, Congress submitted the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, which would have given them representation in the House, Senate, and Electoral College. However, the proposal was only good for seven years and just 16 states ratified it before the seven years were over.

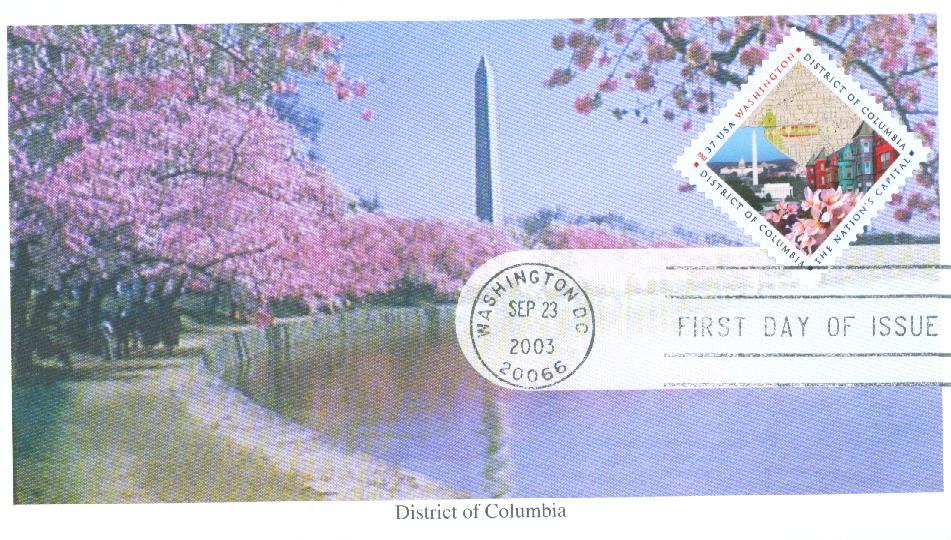

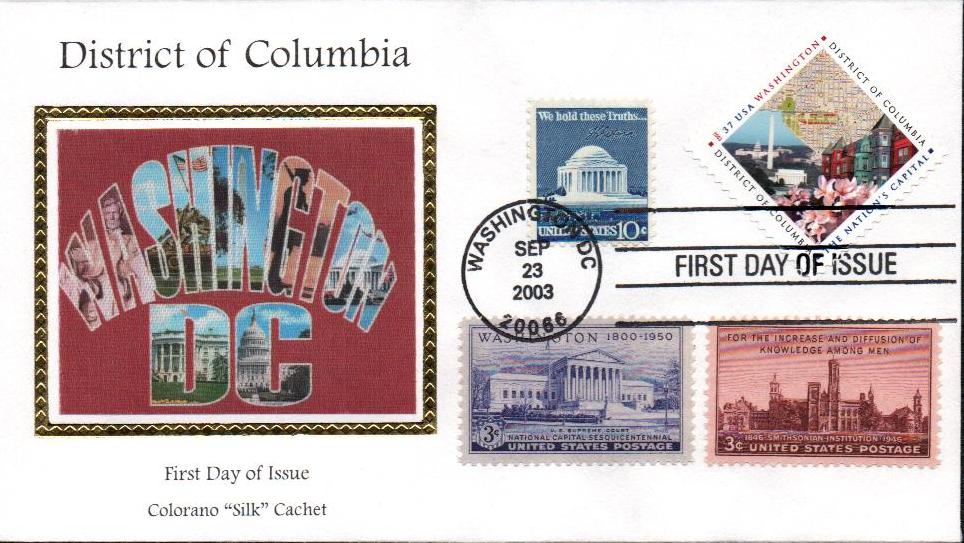

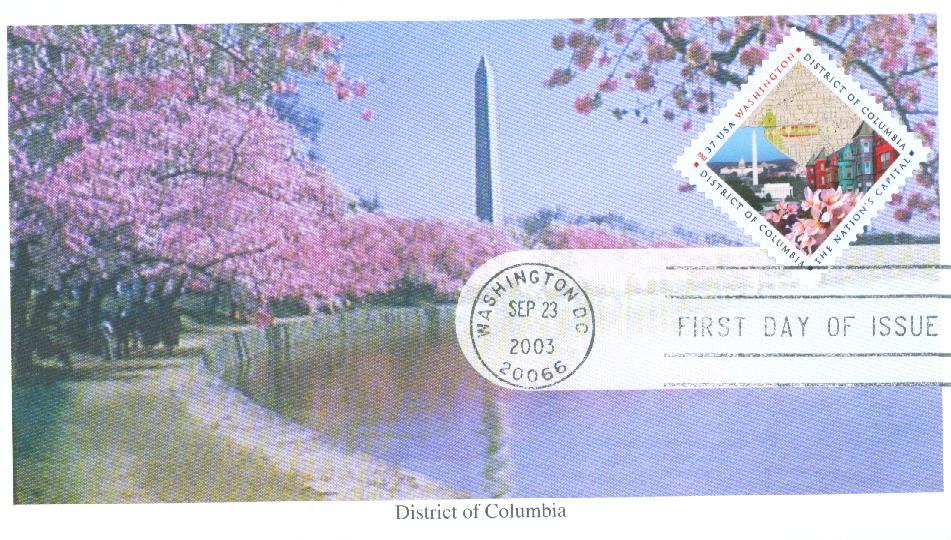

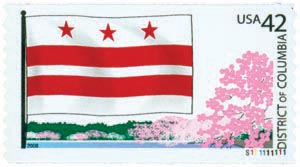

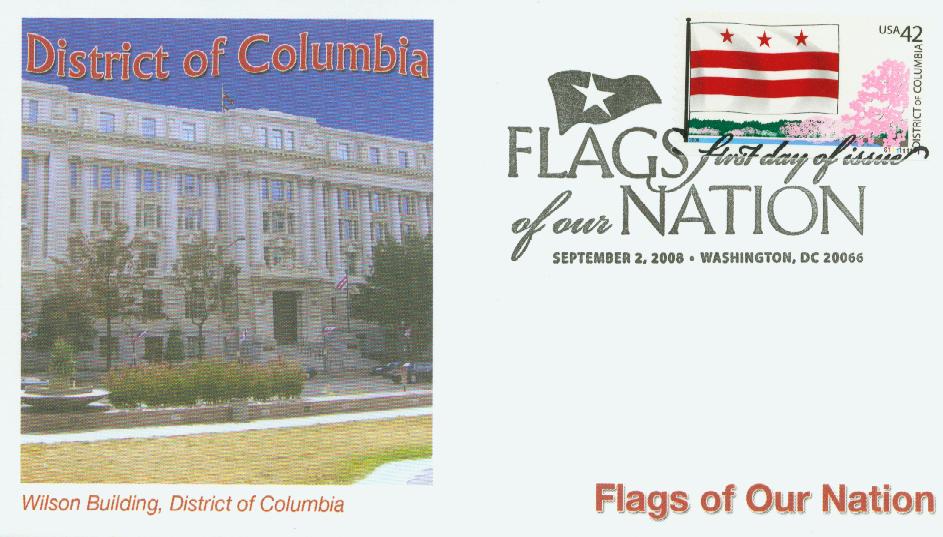

37¢ District of Columbia

City: Washington, D.C.

Quantity: 72,000,000

Printed By: American Packaging Corporation for Sennett Security Products

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cut 11

Color: Multicolored

District Of Columbia

On July 16, 1790, the District of Columbia was established with George Washington’s signing of the Residence Act.

Philadelphia was America’s first capital city starting in 1774. However, in 1783, an angry group of soldiers went to Independence Hall demanding payment for their service during the American Revolution. When Pennsylvania governor John Dickinson refused to remove them, Congress fled to Princeton, New Jersey.

Four years later, the delegates at the Philadelphia Convention granted Congress the power “To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding 10 miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of government of the United States.”

James Madison added that the national capital should be separate from the rest of the states, being responsible for its own maintenance and security. Maryland, New Jersey, New York, and Virginia all offered territory for the capital. Eventually, Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and Alexander Hamilton selected the area around the Potomac River to serve as the national capital.

By 1789, Maryland and Virginia ceded a combined 100 square miles to serve as the capital. On July 9, 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, approving the creation of the national capital on the Potomac River. Days later, President George Washington selected the exact location of the new capital. He then signed the Residence Act on July 16, officially establishing America’s new permanent capital.

In 1791, Washington appointed three commissioners to oversee the planning, design, and creation of property. A major part of this was the naming of the new capital. During the American Revolution, colonists viewed Christopher Columbus as a hero of their nation. They adopted the Roman Goddess of liberty and freedom as their symbol and named her Columbia after Columbus. The commission ultimately named the Federal District “The Territory of Columbia,” and the Federal City “The City of Washington.”

Around this time, President Washington hired Pierre Charles L’Enfant to design the capital city at the center of the federal territory. L’Enfant’s plan revolved around the US Capitol Building on top of Jenkins Hill with wide diagonal avenues crossing the city’s layout. He also designed the narrow Pennsylvania Avenue to connect the Capitol Building and White House. After L’Enfant became involved in several conflicts with the city’s commissioners and refused to provide planners with an engraved city plan, he was let go. Andrew Ellicott made several changes to L’Enfant’s plan and had it engraved, making it the first distributed plan of the city.

In 1800, the national government was officially moved to the new city. The following year, the federal district and the municipalities of Washington, Georgetown, and Alexandria were placed under the control of Congress. In 1802, the City of Washington was granted a territorial government led by a President-appointed mayor. Congress was made responsible for capital improvements and economic development initiatives, but did not have loyalty to the city and often provided little or no support.

In 1846, 39 square miles were returned to Virginia and part of that land later became the Arlington National Cemetery. The capital continued to function during the Civil War and the government grew significantly to oversee the war and was partially responsible for the large increase in the city’s population. Under Robey Shepherd’s governorship in the 1870s, several improvements were introduced, including paved streets and a new sewer system. However, his excessive spending caused Congress to remove the position of governor and take over its control, which lasted for more than 100 years.

At the beginning of the 1900s, the District formed the McMillan Plan, intended to carry out L’Enfant’s unfinished vision of the city. This included removing poor neighborhoods and replacing them with public monuments, government buildings, and new, modern, affordable homes.

Throughout the 20th Century, the nation’s capital was often at the center of civil rights issues. In March 1961, the people of Washington, DC, were finally given the right to choose electors for President and Vice President. And in 1973, Congress granted the district a directly elected city council and mayor. Five years later, Congress submitted the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, which would have given them representation in the House, Senate, and Electoral College. However, the proposal was only good for seven years and just 16 states ratified it before the seven years were over.