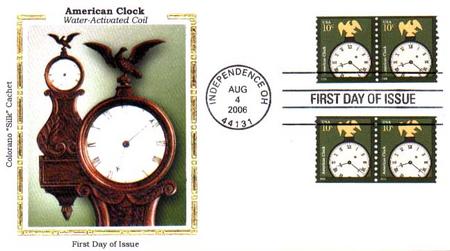

# 3757 - 2003 10c American Clock

10¢ American Clock

American Design

City: Tucson, Arizona

Quantity: 150,000,000

Printed By: Ashton-Potter

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cut 11 ¼ x 11

Color: Black, green, yellow

America Institutes First National Time Zones

On November 18, 1883, U.S. and Canadian railroad companies jointly adopted five standard continental time zones.

Before the invention of clock, communities marked the time of day with apparent solar time, usually with a sundial. This meant the time could be slightly different in each settlement. With the advent of mechanical clocks, people still used the sun, but times could still differ by around 15 minutes.

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was established when the Royal Observatory was built in 1675, giving the people of England a standard reference time. Great Britain railway companies using GMT on portable chronometers adopted the first standard time on December 1, 1847. Even still, it was a difficult transition for people used to using solar time. But it became a necessity for countries to establish time zones domestically as well as for dealings with other countries.

In America, timekeeping was confusing. Railroads had made it possible to journey long distances in short amount of times. But each railroad used its own standard time, often based on the local time of their headquarters or largest station. Cities that had several railroads passing through would have clocks for each railroad, each with a different time.

Charles F. Dowd was one of the first Americans to propose a system of one-hour standard time zones for use by American railroads as early as 1863. He’d shared the idea with a class he was teaching at the time, but didn’t address railroad officials until 1869. Dowd’s suggested time zones weren’t adopted.

Instead, American and Canadian railroad officials chose time zones suggested by William F. Allen, editor of the Traveler’s Official Railway Guide. Allen presented his idea at the General Time Convention of 1883. On October 11 of that year, they officially adopted the current Standard Time System. The new proposed time zones had borders running through railroad stations in major cities such as Detroit, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and Charleston.

Once the railroad companies agreed on the new time zones, they selected a date to institute them and informed the public. Louisville, Kentucky’s The Courier-Journal ran a lengthy article concerning the time zones a few days beforehand.

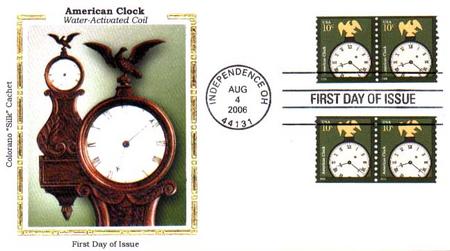

10¢ American Clock

American Design

City: Tucson, Arizona

Quantity: 150,000,000

Printed By: Ashton-Potter

Printing Method: Photogravure

Perforations: Serpentine Die Cut 11 ¼ x 11

Color: Black, green, yellow

America Institutes First National Time Zones

On November 18, 1883, U.S. and Canadian railroad companies jointly adopted five standard continental time zones.

Before the invention of clock, communities marked the time of day with apparent solar time, usually with a sundial. This meant the time could be slightly different in each settlement. With the advent of mechanical clocks, people still used the sun, but times could still differ by around 15 minutes.

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) was established when the Royal Observatory was built in 1675, giving the people of England a standard reference time. Great Britain railway companies using GMT on portable chronometers adopted the first standard time on December 1, 1847. Even still, it was a difficult transition for people used to using solar time. But it became a necessity for countries to establish time zones domestically as well as for dealings with other countries.

In America, timekeeping was confusing. Railroads had made it possible to journey long distances in short amount of times. But each railroad used its own standard time, often based on the local time of their headquarters or largest station. Cities that had several railroads passing through would have clocks for each railroad, each with a different time.

Charles F. Dowd was one of the first Americans to propose a system of one-hour standard time zones for use by American railroads as early as 1863. He’d shared the idea with a class he was teaching at the time, but didn’t address railroad officials until 1869. Dowd’s suggested time zones weren’t adopted.

Instead, American and Canadian railroad officials chose time zones suggested by William F. Allen, editor of the Traveler’s Official Railway Guide. Allen presented his idea at the General Time Convention of 1883. On October 11 of that year, they officially adopted the current Standard Time System. The new proposed time zones had borders running through railroad stations in major cities such as Detroit, Buffalo, Pittsburgh, Atlanta, and Charleston.

Once the railroad companies agreed on the new time zones, they selected a date to institute them and informed the public. Louisville, Kentucky’s The Courier-Journal ran a lengthy article concerning the time zones a few days beforehand.