# 3746 - 2003 37c Black Heritage: Thurgood Marshall

2003 37¢ Thurgood Marshall

Black Heritage Series

City: Washington, DC

Quantity: 150,000,000

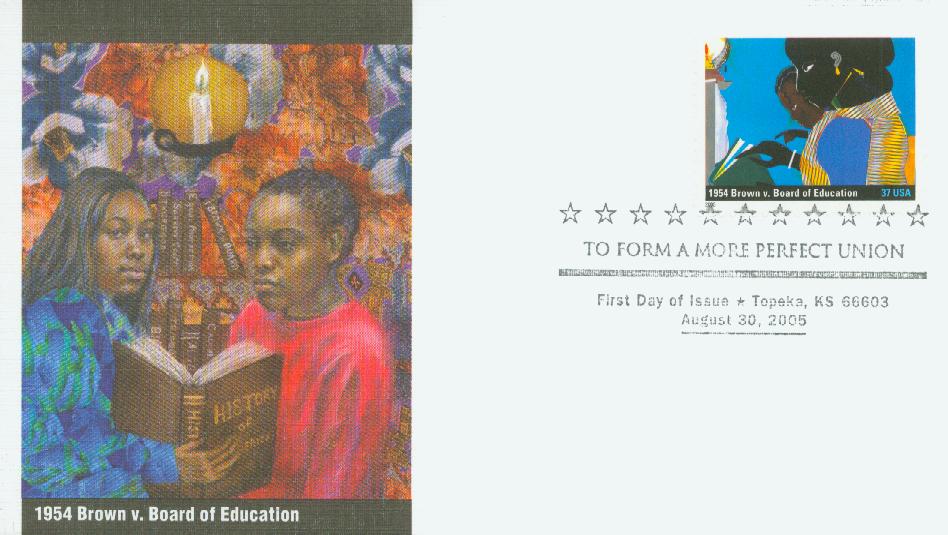

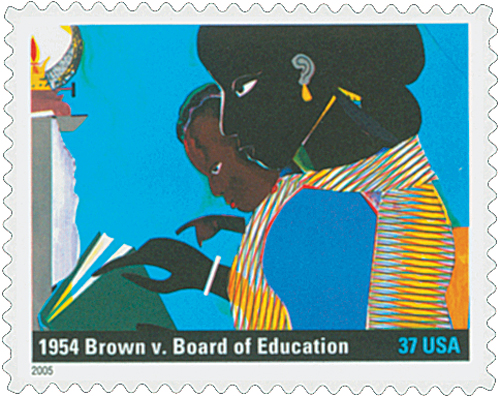

Brown Vs. Board Of Education

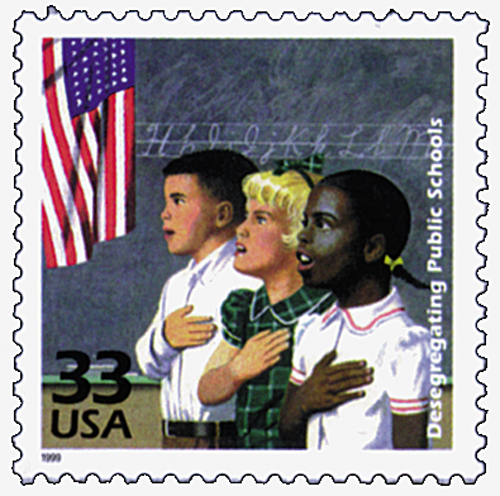

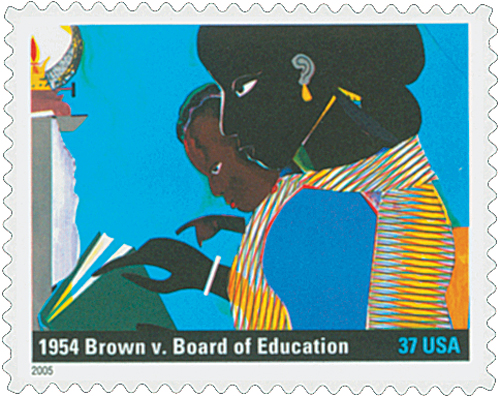

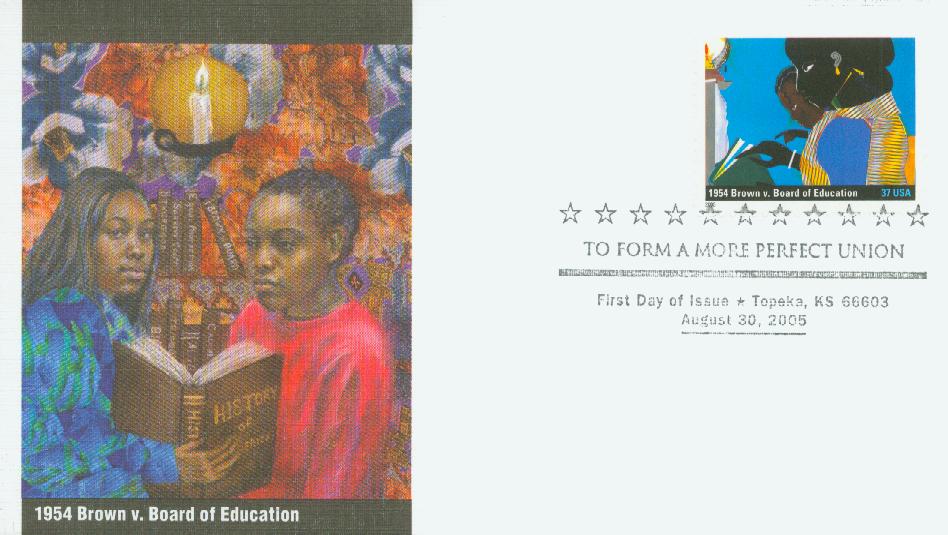

On May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court ordered the desegregation of schools as a result of the case of Brown vs. Board of Education.

Decades earlier, a precedent had been set in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson. That case ruled that as long as the separate facilities for separate races were equal, they didn’t violate the 14th Amendment of equal protection.

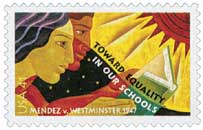

In spite of this ruling, schools were far from equal, and some people fought the segregation of schools. In 1945, Gonzalo Mendez and his family lived in Westminster, California, which had segregated schools. There was a two-room shack for Mexicans and a well-built school with a lawn and other amenities for whites-only. Determined that his children should have a good education, Mendez sued the school system in the case of Mendez vs. Westminster. He won the case and forced them to desegregate. The landmark case set the precedent for Brown vs. Board of Education.

In Topeka, Kansas, seven-year-old Linda Brown had to walk one mile to get to her black elementary school; a white school was only seven blocks away. Mr. Brown tried unsuccessfully to enroll his daughter in the white school. He appealed for help to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In June 1951, the Kansas US District Court heard Brown’s case against the Topeka school board. The NAACP argued that segregated schools sent a message to black children that they were inferior to whites; therefore, the schools were not equal. However, the District Court followed the precedent of Plessy vs. Ferguson, and ruled against Brown.

The NAACP appealed to the US Supreme Court, with future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall presenting the case. The court first heard the case in the spring of 1953, but was unable to reach a decision, and requested to hear it again that fall. The case was reargued on December 8, 1953, and the justices deliberated.

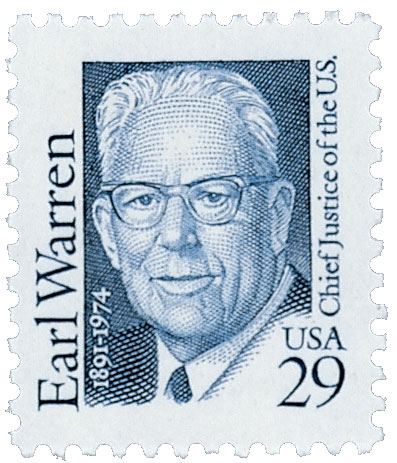

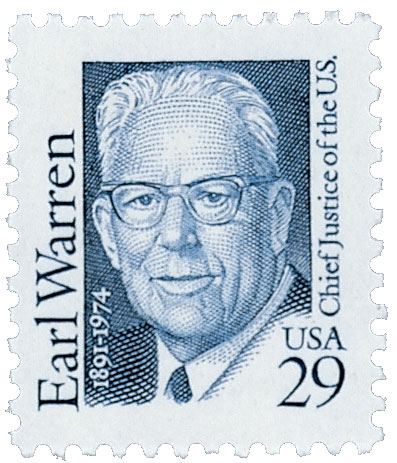

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court announced its decision, striking down the “separate but equal” doctrine for public education and requiring the desegregation of schools across America. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court, saying “in the field of public opinion, the doctrine of separate but equal has no place. Separated educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The decision sparked a movement to desegregate all public facilities across the American South.

Opposition to Brown was fierce. Many white southern Congress members signed the “Southern Manifesto,” condemning the case and declaring the states had the right to ignore it. To avoid desegregation, some officials closed their local public schools.

Three years after the court’s decision, not one southern child attended a desegregated school. That changed in September 1957, when Little Rock’s Central High School was forced to allow nine black students to attend classes there. Governor Orval Faubus prevented their admission for over three weeks. After much tension and unrest, the students were escorted into the school by National Guard units on September 25.

2003 37¢ Thurgood Marshall

Black Heritage Series

City: Washington, DC

Quantity: 150,000,000

Brown Vs. Board Of Education

On May 17, 1954, the US Supreme Court ordered the desegregation of schools as a result of the case of Brown vs. Board of Education.

Decades earlier, a precedent had been set in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson. That case ruled that as long as the separate facilities for separate races were equal, they didn’t violate the 14th Amendment of equal protection.

In spite of this ruling, schools were far from equal, and some people fought the segregation of schools. In 1945, Gonzalo Mendez and his family lived in Westminster, California, which had segregated schools. There was a two-room shack for Mexicans and a well-built school with a lawn and other amenities for whites-only. Determined that his children should have a good education, Mendez sued the school system in the case of Mendez vs. Westminster. He won the case and forced them to desegregate. The landmark case set the precedent for Brown vs. Board of Education.

In Topeka, Kansas, seven-year-old Linda Brown had to walk one mile to get to her black elementary school; a white school was only seven blocks away. Mr. Brown tried unsuccessfully to enroll his daughter in the white school. He appealed for help to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In June 1951, the Kansas US District Court heard Brown’s case against the Topeka school board. The NAACP argued that segregated schools sent a message to black children that they were inferior to whites; therefore, the schools were not equal. However, the District Court followed the precedent of Plessy vs. Ferguson, and ruled against Brown.

The NAACP appealed to the US Supreme Court, with future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall presenting the case. The court first heard the case in the spring of 1953, but was unable to reach a decision, and requested to hear it again that fall. The case was reargued on December 8, 1953, and the justices deliberated.

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court announced its decision, striking down the “separate but equal” doctrine for public education and requiring the desegregation of schools across America. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court, saying “in the field of public opinion, the doctrine of separate but equal has no place. Separated educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The decision sparked a movement to desegregate all public facilities across the American South.

Opposition to Brown was fierce. Many white southern Congress members signed the “Southern Manifesto,” condemning the case and declaring the states had the right to ignore it. To avoid desegregation, some officials closed their local public schools.

Three years after the court’s decision, not one southern child attended a desegregated school. That changed in September 1957, when Little Rock’s Central High School was forced to allow nine black students to attend classes there. Governor Orval Faubus prevented their admission for over three weeks. After much tension and unrest, the students were escorted into the school by National Guard units on September 25.