# 3403k - 2000 33c The Stars and Stripes: Star-Spangled Banner

33¢ Star-Spangled Banner (1814)

The Stars and Stripes

City: Baltimore, MD

Quantity: 4,000,000

Printed by: Banknote of America

Printing Method: Lithographed

Perforations: 10.5 x 11

Color: Multicolored

America Adopts National Anthem

The inspiration for the “Star Spangled Banner” came over a century earlier, during the War of 1812. In September 1814, Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key was dispatched to a British ship to rescue a beloved local doctor.

Key happened to make this journey shortly before the start of the Battle of Fort McHenry. Although he managed to negotiate the doctor’s release, he’d heard the British plans to attack Fort McHenry and was forced to remain on the ship for the 25-hour battle. The next morning he looked to the fort and saw that “the flag was still there.” The British attack had failed. So moved by the sight, he penned the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.”

Although the Battle of Fort McHenry was a major influence, Key also used some wording and imagery from a poem he’d written earlier about Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart for their bravery during the First Barbary War. A few days after the battle, Key took his poem to his brother-in-law, who found that the words would perfectly with the melody John Stafford Smith’s “The Anacreontic Song.” The first broadsides were printed on September 17 and the song first appeared in the Baltimore Patriot and The American newspapers three days later.

Key’s song quickly resonated with Americans and it was published in several more newspapers. Then music store owner Thomas Carr published the words and music together under a new title, “The Star Spangled Banner.” A Baltimore actor named Ferdinand Durang first performed the song publicly in October 1814.

In the coming years, “The Star Spangled Banner” became a popular staple at Fourth of July celebrations and other patriotic events. In 1892, Colonel Caleb Carlton, post commander at Fort Meade, South Dakota, began the practice of playing the song “at retreat and at the close of parades and concerts.” Carlton shared the idea with his state governor and later the Secretary of War, to encourage the practice be instituted nationally among America’s military. As a result of these efforts “The Star Spangled Banner” was made the official tune for the Navy’s flag raisings in July 1889.

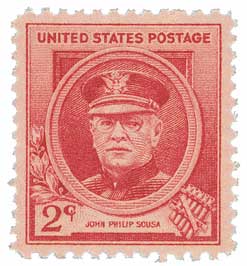

By the early 1900s, there were several different versions of “The Star Spangled Banner,” so president Woodrow Wilson asked the Bureau of Education to standardize it and make an official version. The Bureau hired five musicians, including John Philip Sousa, to complete the task. The standardized song was first performed on December 5, 1917.

The following April, Maryland congressman John Charles Linthicum submitted a bill calling for the “The Star Spangled Banner” to be officially adopted as the national anthem. The bill failed to pass. But Linthicum didn’t give up and continued to submit his proposal five more times. Then in 1929, Robert Ripley produced a cartoon for his Ripley’s Believe it or Not! that said, “Believe It or Not, America has no national anthem.”

33¢ Star-Spangled Banner (1814)

The Stars and Stripes

City: Baltimore, MD

Quantity: 4,000,000

Printed by: Banknote of America

Printing Method: Lithographed

Perforations: 10.5 x 11

Color: Multicolored

America Adopts National Anthem

The inspiration for the “Star Spangled Banner” came over a century earlier, during the War of 1812. In September 1814, Georgetown lawyer Francis Scott Key was dispatched to a British ship to rescue a beloved local doctor.

Key happened to make this journey shortly before the start of the Battle of Fort McHenry. Although he managed to negotiate the doctor’s release, he’d heard the British plans to attack Fort McHenry and was forced to remain on the ship for the 25-hour battle. The next morning he looked to the fort and saw that “the flag was still there.” The British attack had failed. So moved by the sight, he penned the poem “Defence of Fort McHenry.”

Although the Battle of Fort McHenry was a major influence, Key also used some wording and imagery from a poem he’d written earlier about Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart for their bravery during the First Barbary War. A few days after the battle, Key took his poem to his brother-in-law, who found that the words would perfectly with the melody John Stafford Smith’s “The Anacreontic Song.” The first broadsides were printed on September 17 and the song first appeared in the Baltimore Patriot and The American newspapers three days later.

Key’s song quickly resonated with Americans and it was published in several more newspapers. Then music store owner Thomas Carr published the words and music together under a new title, “The Star Spangled Banner.” A Baltimore actor named Ferdinand Durang first performed the song publicly in October 1814.

In the coming years, “The Star Spangled Banner” became a popular staple at Fourth of July celebrations and other patriotic events. In 1892, Colonel Caleb Carlton, post commander at Fort Meade, South Dakota, began the practice of playing the song “at retreat and at the close of parades and concerts.” Carlton shared the idea with his state governor and later the Secretary of War, to encourage the practice be instituted nationally among America’s military. As a result of these efforts “The Star Spangled Banner” was made the official tune for the Navy’s flag raisings in July 1889.

By the early 1900s, there were several different versions of “The Star Spangled Banner,” so president Woodrow Wilson asked the Bureau of Education to standardize it and make an official version. The Bureau hired five musicians, including John Philip Sousa, to complete the task. The standardized song was first performed on December 5, 1917.

The following April, Maryland congressman John Charles Linthicum submitted a bill calling for the “The Star Spangled Banner” to be officially adopted as the national anthem. The bill failed to pass. But Linthicum didn’t give up and continued to submit his proposal five more times. Then in 1929, Robert Ripley produced a cartoon for his Ripley’s Believe it or Not! that said, “Believe It or Not, America has no national anthem.”