1909 13c Washington, blue green, double line watermark

# 339 - 1909 13c Washington, blue green, double line watermark

$0.00 - $725.00

U.S. #339

Series of 1908-09 13¢ Washington

Series of 1908-09 13¢ Washington

Issue Date: January 11, 1909

Quantity issued: 2,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue green

Quantity issued: 2,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue green

U.S. #339 was issued to cover the registration fee plus the single letter rate on letters bound to foreign destinations. The registry fee was increased on November 1, 1909. With its primary reason for being eliminated, officials stopped printing the 13¢ denomination. Sales were low, making #339 nearly as scarce in postally used condition as it is in mint.

The 13¢ denomination was printed solely on standard 2mm spaced plates, and not star plates as seen in the lower values. The stamp is also known on china clay paper, which is similar to blue paper. The china clay paper mistakenly contained 20% china clay instead of the 2% specified. The result is paper that is hard and much thinner than standard or blue paper. The grayish color is much lighter than blue paper when viewed from the back, and is scarcer.

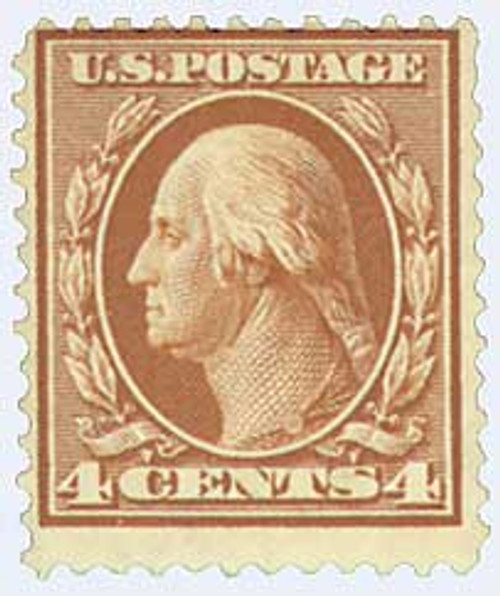

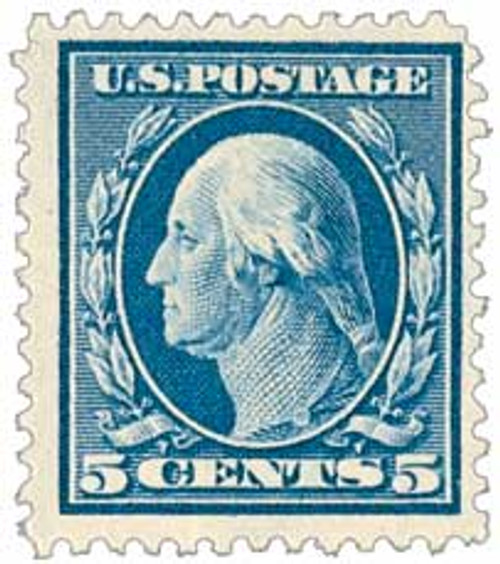

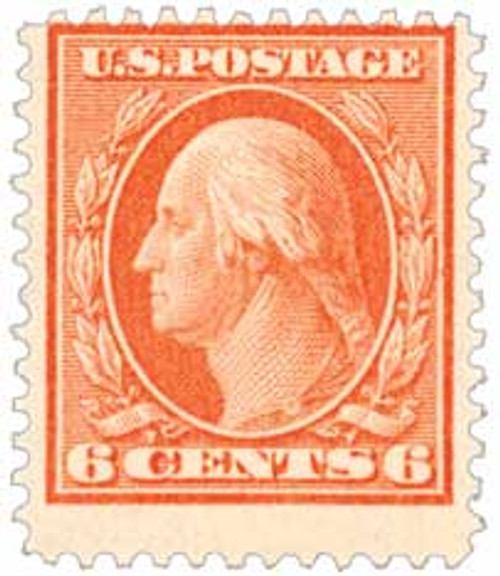

Series of 1908-09

When the 1902 series was issued, the Post Office Department received numerous complaints from collectors, as well as the public, concerning the stamps’ poor designs. One particular gentleman, Charles Dalton, even wrote to his senator! He severely criticized the Stuart portrait of Washington currently in use on the 2¢ stamp and suggested the profile, taken from the bust by Jean Antoine Houdon, be put back into use.

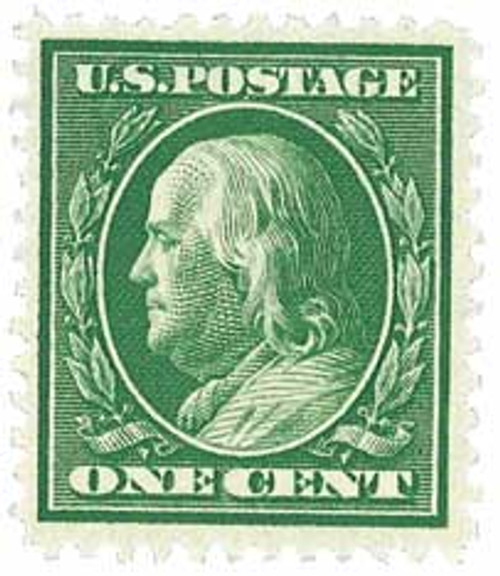

He also recommended that this portrait be used on all U.S. issues. To support his idea, he used the example of Great Britain’s stamps, which all carried the profile portrait of King Edward VII. After careful consideration, the Postmaster General and Department officials adopted Mr. Dalton’s suggestions for the new 1908 series. The decision was made to keep Benjamin Franklin on the 1¢ stamp; however, his portrait was also to be in profile, modeled after Houdon’s bust.

A simpler and more modern-looking border design was selected to be used on all denominations. The simplicity and uniformity of the new design greatly reduced production costs and extended the life of the steel printing plates. Due to lower international rates and higher weight limits per unit, the need for the $2 and $5 stamps diminished. When the 1908 was released, these issues were discontinued.

Issued during the American Industrial Revolution, the series of 1908 was released in an age when machines were being developed to do anything man could and more. These inventions ranged from automated manufacturing plants and flying machines to the horseless carriage and slot machines. These slot or vending machines first appeared in the late 1880s to sell chewing gum on New York City train platforms. By the twentieth century, they also dispensed products such as candy, cigarettes, and souvenir postcards.

These vending machines were so successful that the companies that manufactured them were constantly seeking new items to market. Their attention was soon turned to postage stamps. Not only would this venture prove profitable for the manufacturers, it could also save a sizable amount of money of the government.

On November 24, 1905, a committee was appointed to investigate the possibility of using vending machines to see stamps. The committee was to determine whether or not this would be a worthwhile endeavor for the Postal Department to undertake. After examining the merits of these machines they reported, “...that the adoption of automatic machines for the sale of stamped paper would not, for the present, be advantageous.” The idea was abandoned until 1907.

U.S. #339

Series of 1908-09 13¢ Washington

Series of 1908-09 13¢ Washington

Issue Date: January 11, 1909

Quantity issued: 2,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue green

Quantity issued: 2,905,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Blue green

U.S. #339 was issued to cover the registration fee plus the single letter rate on letters bound to foreign destinations. The registry fee was increased on November 1, 1909. With its primary reason for being eliminated, officials stopped printing the 13¢ denomination. Sales were low, making #339 nearly as scarce in postally used condition as it is in mint.

The 13¢ denomination was printed solely on standard 2mm spaced plates, and not star plates as seen in the lower values. The stamp is also known on china clay paper, which is similar to blue paper. The china clay paper mistakenly contained 20% china clay instead of the 2% specified. The result is paper that is hard and much thinner than standard or blue paper. The grayish color is much lighter than blue paper when viewed from the back, and is scarcer.

Series of 1908-09

When the 1902 series was issued, the Post Office Department received numerous complaints from collectors, as well as the public, concerning the stamps’ poor designs. One particular gentleman, Charles Dalton, even wrote to his senator! He severely criticized the Stuart portrait of Washington currently in use on the 2¢ stamp and suggested the profile, taken from the bust by Jean Antoine Houdon, be put back into use.

He also recommended that this portrait be used on all U.S. issues. To support his idea, he used the example of Great Britain’s stamps, which all carried the profile portrait of King Edward VII. After careful consideration, the Postmaster General and Department officials adopted Mr. Dalton’s suggestions for the new 1908 series. The decision was made to keep Benjamin Franklin on the 1¢ stamp; however, his portrait was also to be in profile, modeled after Houdon’s bust.

A simpler and more modern-looking border design was selected to be used on all denominations. The simplicity and uniformity of the new design greatly reduced production costs and extended the life of the steel printing plates. Due to lower international rates and higher weight limits per unit, the need for the $2 and $5 stamps diminished. When the 1908 was released, these issues were discontinued.

Issued during the American Industrial Revolution, the series of 1908 was released in an age when machines were being developed to do anything man could and more. These inventions ranged from automated manufacturing plants and flying machines to the horseless carriage and slot machines. These slot or vending machines first appeared in the late 1880s to sell chewing gum on New York City train platforms. By the twentieth century, they also dispensed products such as candy, cigarettes, and souvenir postcards.

These vending machines were so successful that the companies that manufactured them were constantly seeking new items to market. Their attention was soon turned to postage stamps. Not only would this venture prove profitable for the manufacturers, it could also save a sizable amount of money of the government.

On November 24, 1905, a committee was appointed to investigate the possibility of using vending machines to see stamps. The committee was to determine whether or not this would be a worthwhile endeavor for the Postal Department to undertake. After examining the merits of these machines they reported, “...that the adoption of automatic machines for the sale of stamped paper would not, for the present, be advantageous.” The idea was abandoned until 1907.