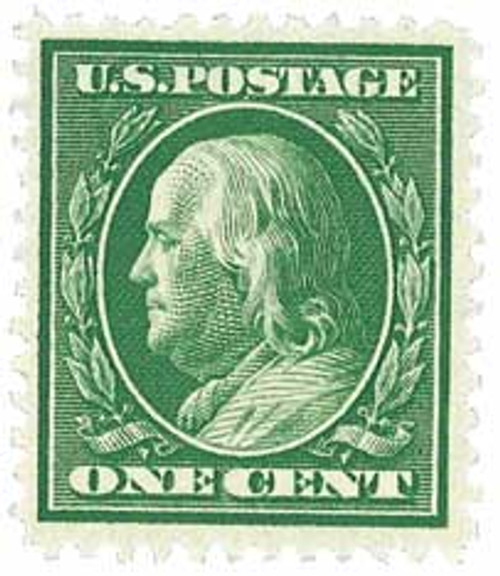

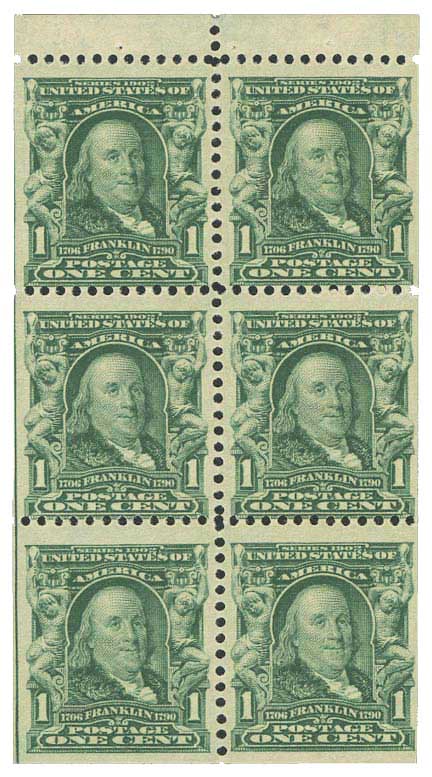

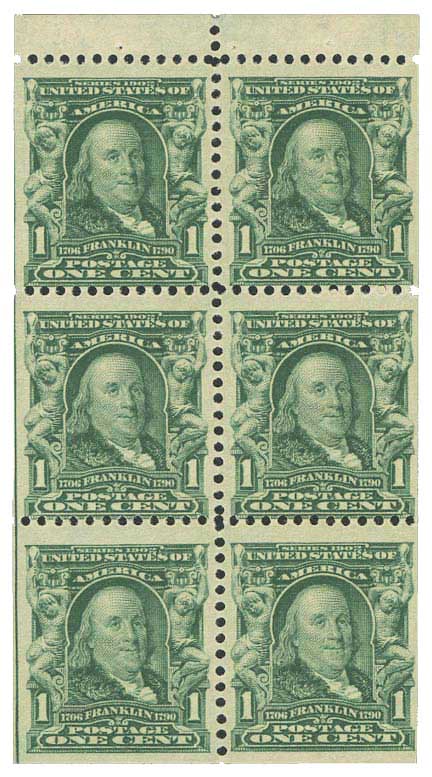

# 331a - 1908 1c Franklin, DL Wmrk, bklt pane

Series of 1908-09 1¢ Franklin

Quantity issued: 5,300,000,000 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Green

First U.S. Stamp Books

In 1884, a man named Albert W. Cooke of Boston received a patent for a “Book for Holding Stamps.” Cooke’s design was for a small book that could fit in a vest pocket that had alternating pages of stamps and paper treated with wax “so that the gummed side of the stamps shall not stick to it under the action of heat or moisture.”

It’s unknown whether or not Cooke shared his idea with the post office at the time, however it would be 16 years before they would adopt a similar idea. By early 1900, Captain P.C. Bane, a bookbinder at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) had started creating stamp booklets for his personal use. He would place blocks of stamps in between pieces of cardboard and lunch paper for convenience. He thought it was a good idea, so he shared it with the director of the BEP.

The director agreed it was a good idea and in turn shared it with the post master general. The postmaster agreed as well, and on March 26, 1900, ordered that stamp books be prepared for public use. On April 18 (some sources say April 16), the first US stamp books were placed on sale for the public. The post office offered the books in three sizes. Each book only had 2¢ stamps, but customers could choose between 12, 24, and 48 stamps in a book. The books were sold at 1¢ over the face value (so the 12-stamp book sold for 25¢, etc.)

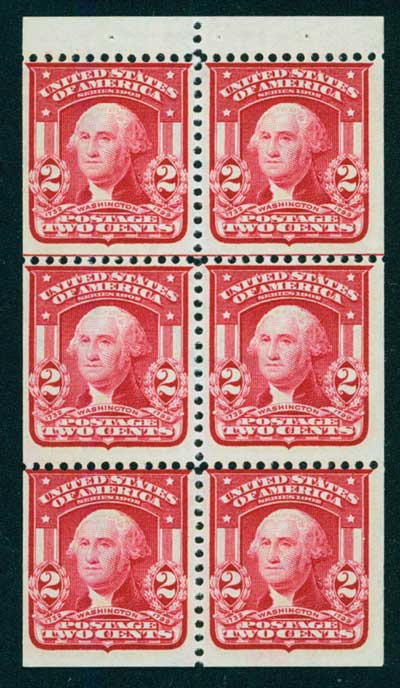

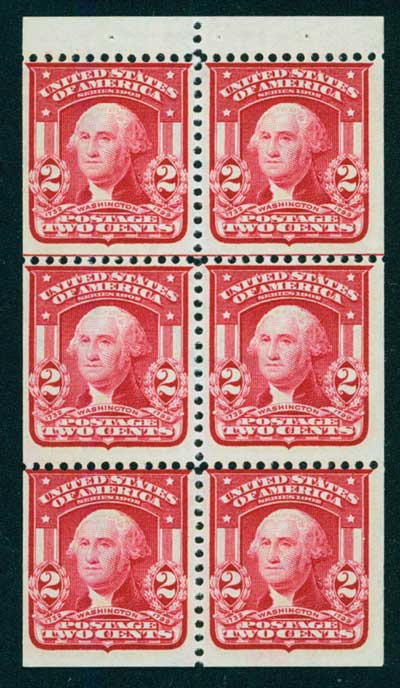

Each book contained sheets of six stamps with paraffined paper between them to prevent sticking. The cardboard covers had domestic and foreign postage rates printed on them, as well as information about the money order and registry systems. The books proved to be very popular with the general public and several post offices sold out of their supplies on the first day they were placed on sale. In the coming months, the post office quickly perfected their system for making the books and were able to produce 20,000 per day at a cost of $3.85 per thousand.

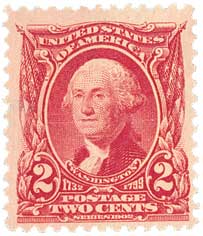

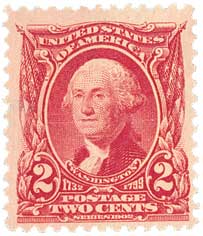

The stamps used for the first run of books were Scott #279Bj, the red 2¢ Washington from the Universal Postal Union Colors series. In January 1903, the booklets were made with the new ornate 2¢ Washington “flag” stamp, #301c. However, the regular #301 stamp had proven unpopular and was redesigned, with a shield replacing the flags that flanked Washington’s portrait, and the book stamp #319g was issued that December.

It would be a few more years before the books would be produced with another denomination. In 1907, the postmaster general reported that there had been increasing demand for 1¢ stamps due to the rising popularity of illustrated post cards. So they used the same book format that had been previously created for the 1¢ stamps.

In late 1908, the postmaster sought to create more appealing books. He thought the current covers were plain, so the new ones were imprinted with the post office department’s official seal. The back of the books showcased the model form of an address.

Stamp booklets continued to carry a 1¢ premium until 1963. They’re still in use today, proving popular and convenient for mailers.

Series of 1908-09 1¢ Franklin

Quantity issued: 5,300,000,000 (estimate)

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: Double line

Perforation: 12

Color: Green

First U.S. Stamp Books

In 1884, a man named Albert W. Cooke of Boston received a patent for a “Book for Holding Stamps.” Cooke’s design was for a small book that could fit in a vest pocket that had alternating pages of stamps and paper treated with wax “so that the gummed side of the stamps shall not stick to it under the action of heat or moisture.”

It’s unknown whether or not Cooke shared his idea with the post office at the time, however it would be 16 years before they would adopt a similar idea. By early 1900, Captain P.C. Bane, a bookbinder at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) had started creating stamp booklets for his personal use. He would place blocks of stamps in between pieces of cardboard and lunch paper for convenience. He thought it was a good idea, so he shared it with the director of the BEP.

The director agreed it was a good idea and in turn shared it with the post master general. The postmaster agreed as well, and on March 26, 1900, ordered that stamp books be prepared for public use. On April 18 (some sources say April 16), the first US stamp books were placed on sale for the public. The post office offered the books in three sizes. Each book only had 2¢ stamps, but customers could choose between 12, 24, and 48 stamps in a book. The books were sold at 1¢ over the face value (so the 12-stamp book sold for 25¢, etc.)

Each book contained sheets of six stamps with paraffined paper between them to prevent sticking. The cardboard covers had domestic and foreign postage rates printed on them, as well as information about the money order and registry systems. The books proved to be very popular with the general public and several post offices sold out of their supplies on the first day they were placed on sale. In the coming months, the post office quickly perfected their system for making the books and were able to produce 20,000 per day at a cost of $3.85 per thousand.

The stamps used for the first run of books were Scott #279Bj, the red 2¢ Washington from the Universal Postal Union Colors series. In January 1903, the booklets were made with the new ornate 2¢ Washington “flag” stamp, #301c. However, the regular #301 stamp had proven unpopular and was redesigned, with a shield replacing the flags that flanked Washington’s portrait, and the book stamp #319g was issued that December.

It would be a few more years before the books would be produced with another denomination. In 1907, the postmaster general reported that there had been increasing demand for 1¢ stamps due to the rising popularity of illustrated post cards. So they used the same book format that had been previously created for the 1¢ stamps.

In late 1908, the postmaster sought to create more appealing books. He thought the current covers were plain, so the new ones were imprinted with the post office department’s official seal. The back of the books showcased the model form of an address.

Stamp booklets continued to carry a 1¢ premium until 1963. They’re still in use today, proving popular and convenient for mailers.