# 2975h - 1995 32c Civil War: Frederick Douglass

U.S. #2975h

1995 32¢ Frederick Douglass

Civil War

- Issued for the 130th anniversary of the Civil War

- From the second pane in the Classic Collections Series

- Declared the most popular stamps of 1995 by the USPS

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Civil War 130th Anniversary

Value: 32¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: June 29, 1995

First Day City: Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Quantity Issued: 15,000,000

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: To mark the 130th anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

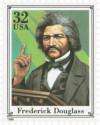

About the stamp design: The Civil War stamps featured artwork by Mark Hess, who had previously produced the artwork for the Legends of the West sheet. The USPS explained that they liked his painting style because of its “folksy stiffness,” that “emulates people standing uncomfortably in front of daguerreotype cameras.”

Known for his eloquent speeches, Frederick Douglass is pictured giving a speech on his stamp. Hess used several photos as the basis of Douglass’s face. The background was made solid green to set it apart from many of the other stamps’ blue and yellow backgrounds.

First Day City: The official first day ceremony was held at the Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania, the site of one of the war’s most famous battles. Because they received a large number of requests, the USPS made the stamps available for sale across the country the same day.

Unusual facts about the Civil War stamps: The Civil War sheet was available by mail order in uncut press sheets of six panes. Of these, 20,000 were signed by stamp artist Mark Hess. The USPS also produced a set of postcards featuring the same images as the stamps (US #UX200-19). Imperforate and partially imperforate error panes have also been found.

About the Civil War Stamps: The Civil War stamp sheet featured 16 individuals – eight from the Union and eight from the Confederacy. The four battles in the corners included one victory for each side and two that are considered draws.

This was the second sheet in the Classic Collections Series following the famed Legends of the West sheet. Stamps in this series follow a similar format – 20 stamps, a decorative header, and information about each stamp printed on its back under the gum.

Plans for the Civil War sheet began while the 1994 Legends of the West sheet was still in its planning stage. The USPS believed that the Civil War was a natural addition to the new series and would be informational for the public. Initially the Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee rejected the idea, saying they should wait 20 years for the 50th anniversary of the war. But they were eventually swayed and the Civil War stamps were created. A group of historians were tasked with making a list of protentional subjects and Shelby Foote was hired to make the final selections. Foote was an expert in the Civil War, having written a three-volume history of the war and been featured in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary series on the war.

The USPS wanted the Civil War stamps to have more action to them – so only the two presidents were depicted in traditional portraits. The rest of the individuals were placed in the field or amidst an activity. After the Legends of the West mix-up, in which the Bill Pickett stamp mistakenly pictured his brother Ben, the USPS completely revamped their research process. The release of the 20 Civil War stamps marked the most extensive effort in the history of the USPS to review and verify the historical accuracy of stamp subjects. As Hess completed each version of his paintings, they were sent to a panel of experts who commented on the historical accuracy of everything from the weather to belt buckles.

Some of the people and battles featured in the Civil War sheet had appeared on US stamps before. This was also the second time the Civil War was honored – a set of five stamps (US #1178-82) was issued for the centennial in the 1960s. And from 2011-15, the USPS issued a series of stamps for the war’s 150th anniversary (US #4522/4981).

History the stamp represents: While the exact date of Frederick Douglass’ birth is unknown, it’s generally considered to be February 14, 1818. Douglass chose the date himself, reportedly because his mother used to call him her “little valentine.”

Born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (he adopted the surname Douglass years later), he was separated from his mother at a young age and lived with his maternal grandmother. When he was seven, he began working on the Wye House plantation as a slave.

From there Douglass went to work for the Aud family in Baltimore. Mrs. Aud taught him to read, against her husband’s wishes, and eventually discouraged the practice. But Douglass continued to learn from neighborhood children and the men he worked with. Douglass then began teaching other slaves to read for about six months, until their masters found out and broke up their meetings.

Douglass was loaned out to several different masters during his life in Maryland. In 1837, Douglass met Anna Murray – a free African American woman living in Baltimore – and fell in love. Her free status gave Douglass the motivation he needed to escape Maryland on September 3, 1838. He ended up in New York City less than 24 hours after he left. After Murray arrived they got married and took the name of Johnson. They then moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts and adopted the name Douglass, after the character in the poem, The Lady of the Lake.

Douglass joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and became a licensed preacher in 1839. He gained valuable experience as an orator and eventually traveled the country with other speakers talking about his life as a slave. In 1845 Douglass published his first autobiography. It was an instant bestseller that was reprinted nine times. However, the book brought attention to his former owner, so Douglass, at the suggestion of his friends, went to Ireland and Britain for two years to deliver rousing lectures. His supporters then raised the funds to buy his freedom, allowing him to return to America in 1847 and begin publishing his first abolitionist paper, The North Star.

The following year, Douglass was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention on women’s rights. At first, many at the convention did not want suffrage included in the “Declaration of Sentiments.” They thought it was too radical a step and that it would discourage people from taking their cause seriously. Douglass stepped up and spoke in support of the idea. He even went so far as to say he wouldn’t feel right about being able to vote if women couldn’t also. His words inspired the attendees and ultimately persuaded them to keep the right to vote in the document.

Throughout the 1850s, Douglass worked with several abolitionist groups. He also became an early supporter of school desegregation. He was appalled at the poor conditions of African American educational facilities compared to those for white children. He considered the matter to be more important than suffrage. Also in the 1850s, Douglass befriended John Brown, and disapproved of his raid on Harpers Ferry. He fled the country for a time, fearing he might be persecuted just for knowing and meeting with Brown, though he didn’t participate in the raid.

By the time the Civil War began, Douglass was one of the most famous African Americans in the country. President Lincoln sought his advice on the treatment of black soldiers and called Douglass the most meritorious man of the nineteenth century. Douglass also helped recruit men to fight for the North. Though Douglass had a good relationship with Lincoln, he supported John C. Frémont in the election of 1864 because Lincoln’s didn’t publicly endorse suffrage for African American freedmen. However, after Lincoln’s death, Douglass called him America’s “greatest President.”

On April 14, 1876, Douglass was the main speaker at the unveiling of the Lincoln Emancipation Statue in Capitol Hill Park, Washington, D.C. He spoke briefly of President Lincoln’s imperfections, but mostly talked about how everything had led to slavery’s end and the restoration of the Union. Over 25,000 people attended the event, including President Ulysses S. Grant, his cabinet, and members of Congress.

Douglass continued to work for African American and women’s equality. He also received several political appointments, including president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and chargé d’affaires for the Dominican Republic. He was an ardent supporter of Ulysses S. Grant’s run for the presidency and applauded his Civil Rights and Enforcements Acts. In 1872, Douglass was the first African American to be nominated for Vice President.

In 1877, Frederick Douglass became the first African American U.S. Marshal. He was appointed by President Rutherford B. Hayes and was responsible for Marshal duties in Washington, D.C. The only duty Douglass did not take on was that of introducing visiting dignitaries to the President.

On January 2, 1893, Douglass dedicated the Haiti pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. Douglass, who had served as the United State’s minister to the country from 1889 to 1891, made a crowd-pleasing speech about Haiti and its people. He talked about their fight for independence and the effect it had on the country and its people. Douglass spoke about the greatness of their success and how it resembled the United States’ own revolution.

Douglass made his final public appearance on February 20, 1895, at a meeting of the National Council of Women, and died after returning home that day.

U.S. #2975h

1995 32¢ Frederick Douglass

Civil War

- Issued for the 130th anniversary of the Civil War

- From the second pane in the Classic Collections Series

- Declared the most popular stamps of 1995 by the USPS

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Civil War 130th Anniversary

Value: 32¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: June 29, 1995

First Day City: Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Quantity Issued: 15,000,000

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: To mark the 130th anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

About the stamp design: The Civil War stamps featured artwork by Mark Hess, who had previously produced the artwork for the Legends of the West sheet. The USPS explained that they liked his painting style because of its “folksy stiffness,” that “emulates people standing uncomfortably in front of daguerreotype cameras.”

Known for his eloquent speeches, Frederick Douglass is pictured giving a speech on his stamp. Hess used several photos as the basis of Douglass’s face. The background was made solid green to set it apart from many of the other stamps’ blue and yellow backgrounds.

First Day City: The official first day ceremony was held at the Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania, the site of one of the war’s most famous battles. Because they received a large number of requests, the USPS made the stamps available for sale across the country the same day.

Unusual facts about the Civil War stamps: The Civil War sheet was available by mail order in uncut press sheets of six panes. Of these, 20,000 were signed by stamp artist Mark Hess. The USPS also produced a set of postcards featuring the same images as the stamps (US #UX200-19). Imperforate and partially imperforate error panes have also been found.

About the Civil War Stamps: The Civil War stamp sheet featured 16 individuals – eight from the Union and eight from the Confederacy. The four battles in the corners included one victory for each side and two that are considered draws.

This was the second sheet in the Classic Collections Series following the famed Legends of the West sheet. Stamps in this series follow a similar format – 20 stamps, a decorative header, and information about each stamp printed on its back under the gum.

Plans for the Civil War sheet began while the 1994 Legends of the West sheet was still in its planning stage. The USPS believed that the Civil War was a natural addition to the new series and would be informational for the public. Initially the Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee rejected the idea, saying they should wait 20 years for the 50th anniversary of the war. But they were eventually swayed and the Civil War stamps were created. A group of historians were tasked with making a list of protentional subjects and Shelby Foote was hired to make the final selections. Foote was an expert in the Civil War, having written a three-volume history of the war and been featured in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary series on the war.

The USPS wanted the Civil War stamps to have more action to them – so only the two presidents were depicted in traditional portraits. The rest of the individuals were placed in the field or amidst an activity. After the Legends of the West mix-up, in which the Bill Pickett stamp mistakenly pictured his brother Ben, the USPS completely revamped their research process. The release of the 20 Civil War stamps marked the most extensive effort in the history of the USPS to review and verify the historical accuracy of stamp subjects. As Hess completed each version of his paintings, they were sent to a panel of experts who commented on the historical accuracy of everything from the weather to belt buckles.

Some of the people and battles featured in the Civil War sheet had appeared on US stamps before. This was also the second time the Civil War was honored – a set of five stamps (US #1178-82) was issued for the centennial in the 1960s. And from 2011-15, the USPS issued a series of stamps for the war’s 150th anniversary (US #4522/4981).

History the stamp represents: While the exact date of Frederick Douglass’ birth is unknown, it’s generally considered to be February 14, 1818. Douglass chose the date himself, reportedly because his mother used to call him her “little valentine.”

Born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey (he adopted the surname Douglass years later), he was separated from his mother at a young age and lived with his maternal grandmother. When he was seven, he began working on the Wye House plantation as a slave.

From there Douglass went to work for the Aud family in Baltimore. Mrs. Aud taught him to read, against her husband’s wishes, and eventually discouraged the practice. But Douglass continued to learn from neighborhood children and the men he worked with. Douglass then began teaching other slaves to read for about six months, until their masters found out and broke up their meetings.

Douglass was loaned out to several different masters during his life in Maryland. In 1837, Douglass met Anna Murray – a free African American woman living in Baltimore – and fell in love. Her free status gave Douglass the motivation he needed to escape Maryland on September 3, 1838. He ended up in New York City less than 24 hours after he left. After Murray arrived they got married and took the name of Johnson. They then moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts and adopted the name Douglass, after the character in the poem, The Lady of the Lake.

Douglass joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and became a licensed preacher in 1839. He gained valuable experience as an orator and eventually traveled the country with other speakers talking about his life as a slave. In 1845 Douglass published his first autobiography. It was an instant bestseller that was reprinted nine times. However, the book brought attention to his former owner, so Douglass, at the suggestion of his friends, went to Ireland and Britain for two years to deliver rousing lectures. His supporters then raised the funds to buy his freedom, allowing him to return to America in 1847 and begin publishing his first abolitionist paper, The North Star.

The following year, Douglass was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention on women’s rights. At first, many at the convention did not want suffrage included in the “Declaration of Sentiments.” They thought it was too radical a step and that it would discourage people from taking their cause seriously. Douglass stepped up and spoke in support of the idea. He even went so far as to say he wouldn’t feel right about being able to vote if women couldn’t also. His words inspired the attendees and ultimately persuaded them to keep the right to vote in the document.

Throughout the 1850s, Douglass worked with several abolitionist groups. He also became an early supporter of school desegregation. He was appalled at the poor conditions of African American educational facilities compared to those for white children. He considered the matter to be more important than suffrage. Also in the 1850s, Douglass befriended John Brown, and disapproved of his raid on Harpers Ferry. He fled the country for a time, fearing he might be persecuted just for knowing and meeting with Brown, though he didn’t participate in the raid.

By the time the Civil War began, Douglass was one of the most famous African Americans in the country. President Lincoln sought his advice on the treatment of black soldiers and called Douglass the most meritorious man of the nineteenth century. Douglass also helped recruit men to fight for the North. Though Douglass had a good relationship with Lincoln, he supported John C. Frémont in the election of 1864 because Lincoln’s didn’t publicly endorse suffrage for African American freedmen. However, after Lincoln’s death, Douglass called him America’s “greatest President.”

On April 14, 1876, Douglass was the main speaker at the unveiling of the Lincoln Emancipation Statue in Capitol Hill Park, Washington, D.C. He spoke briefly of President Lincoln’s imperfections, but mostly talked about how everything had led to slavery’s end and the restoration of the Union. Over 25,000 people attended the event, including President Ulysses S. Grant, his cabinet, and members of Congress.

Douglass continued to work for African American and women’s equality. He also received several political appointments, including president of the Freedman’s Savings Bank and chargé d’affaires for the Dominican Republic. He was an ardent supporter of Ulysses S. Grant’s run for the presidency and applauded his Civil Rights and Enforcements Acts. In 1872, Douglass was the first African American to be nominated for Vice President.

In 1877, Frederick Douglass became the first African American U.S. Marshal. He was appointed by President Rutherford B. Hayes and was responsible for Marshal duties in Washington, D.C. The only duty Douglass did not take on was that of introducing visiting dignitaries to the President.

On January 2, 1893, Douglass dedicated the Haiti pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois. Douglass, who had served as the United State’s minister to the country from 1889 to 1891, made a crowd-pleasing speech about Haiti and its people. He talked about their fight for independence and the effect it had on the country and its people. Douglass spoke about the greatness of their success and how it resembled the United States’ own revolution.

Douglass made his final public appearance on February 20, 1895, at a meeting of the National Council of Women, and died after returning home that day.