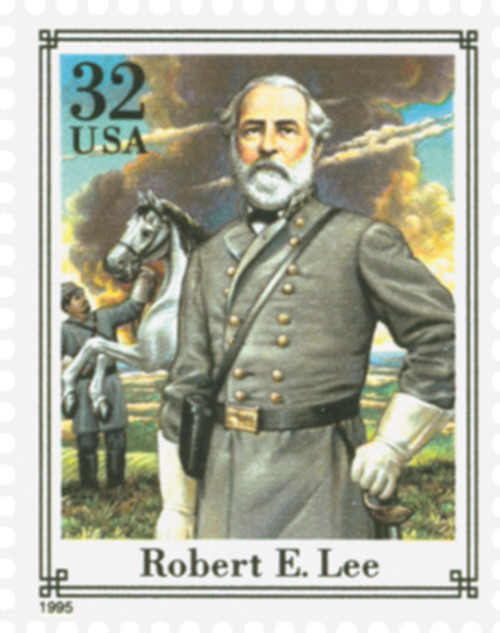

# 2975b - 1995 32c Civil War: Robert E. Lee

U.S. #2975b

1995 32¢ Robert E. Lee

Civil War

- Issued for the 130th anniversary of the Civil War

- From the second pane in the Classic Collections Series

- Declared the most popular stamps of 1995 by the USPS

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Civil War 130th Anniversary

Value: 32¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: June 29, 1995

First Day City: Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Quantity Issued: 15,000,000

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: To mark the 130th anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

About the stamp design: The Civil War stamps featured artwork by Mark Hess, who had previously produced the artwork for the Legends of the West sheet. The USPS explained that they liked his painting style because of its “folksy stiffness,” that “emulates people standing uncomfortably in front of daguerreotype cameras.”

According to Hess, his portrait of Robert E. Lee was in “the grand manner style of painting.” He wanted to “show Lee as an incredibly proud, heroic figure…. That was appropriate to his character.” He depicted Lee in his field uniform with his colonel’s stars (rather than his dress uniform which would have carried his general’s wreath. Behind Lee, his horse Traveller is rearing while being handled by an aide with dark clouds, smoke, and fire in the background.

First Day City: The official first day ceremony was held at the Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania, the site of one of the war’s most famous battles. Because they received a large number of requests, the USPS made the stamps available for sale across the country the same day.

Unusual facts about the Civil War stamps: The Civil War sheet was available by mail order in uncut press sheets of six panes. Of these, 20,000 were signed by stamp artist Mark Hess. The USPS also produced a set of postcards featuring the same images as the stamps (US #UX200-19). Imperforate and partially imperforate error panes have also been found.

About the Civil War Stamps: The Civil War stamp sheet featured 16 individuals – eight from the Union and eight from the Confederacy. The four battles in the corners included one victory for each side and two that are considered draws.

This was the second sheet in the Classic Collections Series following the famed Legends of the West sheet. Stamps in this series follow a similar format – 20 stamps, a decorative header, and information about each stamp printed on its back under the gum.

Plans for the Civil War sheet began while the 1994 Legends of the West sheet was still in its planning stage. The USPS believed that the Civil War was a natural addition to the new series and would be informational for the public. Initially the Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee rejected the idea, saying they should wait 20 years for the 50th anniversary of the war. But they were eventually swayed and the Civil War stamps were created. A group of historians were tasked with making a list of protentional subjects and Shelby Foote was hired to make the final selections. Foote was an expert in the Civil War, having written a three-volume history of the war and been featured in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary series on the war.

The USPS wanted the Civil War stamps to have more action to them – so only the two presidents were depicted in traditional portraits. The rest of the individuals were placed in the field or amidst an activity. After the Legends of the West mix-up, in which the Bill Pickett stamp mistakenly pictured his brother Ben, the USPS completely revamped their research process. The release of the 20 Civil War stamps marked the most extensive effort in the history of the USPS to review and verify the historical accuracy of stamp subjects. As Hess completed each version of his paintings, they were sent to a panel of experts who commented on the historical accuracy of everything from the weather to belt buckles.

Some of the people and battles featured in the Civil War sheet had appeared on US stamps before. This was also the second time the Civil War was honored – a set of five stamps (US #1178-82) was issued for the centennial in the 1960s. And from 2011-15, the USPS issued a series of stamps for the war’s 150th anniversary (US #4522/4981).

History the stamp represents: Descended from one of Virginia’s first families, Robert E. Lee was born on January 19, 1807, in Stratford Hall, Virginia. He was the son of Revolutionary War hero Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee.

Lee’s father’s unfortunate financial choices and early death left his widow with several children and little money. However, a relative helped secure Robert’s appointment to West Point, where he graduated second in his class without incurring any demerits during his four years of study.

In June 1829, Lee was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers and sent to build a fort in the Savannah River. This assignment was followed by a stint at Fort Monroe, Virginia. During the summer of 1829, Lee began courting Martha Washington’s great-granddaughter, Mary Custis, who had also captured the attention of Sam Houston (who would eventually become a southern governor opposed to secession). Robert and Mary were wed on June 30, 1831, at Custis’ home at Arlington House.

Lee continued his military career and was often stationed at remote outposts. Although she had been raised in an affluent household with servants, Mary chose to accompany her husband much of the time. Eventually, she was forced to remain at Arlington due to the birth of seven children and her declining health.

Lee distinguished himself during the Mexican-American War, where he was one of Winfield Scott’s chief aides and met Ulysses S. Grant. After the war, Lee was stationed closer to home and was appointed Superintendent of West Point in 1852.

As the slavery debate ignited, President James Buchanan gave Lee command of a detachment to suppress John Brown and retake the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Lee described Brown as a “fanatic or madman.”

When Texas seceded in February 1861, General David E. Twiggs surrendered all American forces under his command, which included Lee, to the Texans. Lee returned to the capital and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry, an order that was signed by Lincoln. He was promoted to colonel on March 28, turning down an offer to command the Confederate Army. However, Lincoln’s call for troops to put down the rebellion was the catalyst for Virginia’s secession, and Lee’s first duty was to his state.

As dawn approached on April 20, 1861, Robert E. Lee penned a letter to a relative. “I have been unable to make up my mind to raise my hand against my native state, my relations, my children, and my home.” Moments earlier, Lee had sent a letter to the War Department announcing his resignation and ending a distinguished 32-year U.S. military career.

Lee’s decision was astounding. His ancestors included some of the nation’s greatest patriots. A day earlier, as events unfolded following the attack on Fort Sumter, Lee had been offered command of the volunteers defending the nation’s capital.

As war became certain, the Lee clan was forced to take sides. Lee’s wife and sister were devout Unionists, while his daughter believed firmly in secession. The general’s brothers remained faithful to their military oaths, as did his cousins. Lee opposed secession but his sense of duty to Virginia was stronger.

After resigning from the U.S. Army on April 20, Lee took command of the Virginia state forces three days later. Fearing for his wife’s safety – Arlington House was directly across the Potomac River from the nation’s capital – Lee convinced Mary to vacate their home. Federal troops quickly seized the mansion. Mary would return for a brief visit several years later, but Robert E. Lee never saw his home again.

Lee was named one of the Confederate Army’s first five full generals. Soon after, he was defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain and widely credited with causing the loss. After General Joseph E. Johnston’s wounding at the Battle of Seven Pines, Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. His aggressive tactics unnerved Union General George McClellan, leading to a string of decisive Union defeats and a turnaround in public opinion.

A string of Confederate victories followed – Chancellorsville, Cold Harbor, Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, The Wilderness, Seven Days Battles, and Second Manassas. Lee fought McClellan to a draw at Antietam. But by 1863, the Confederate fronts were crumbling in the West. His invasion of Pennsylvania, which was partly to seize urgently needed supplies for his desperate troops, ended with a crushing defeat at Gettysburg.

Although Lee was a brilliant tactician and a daring battlefield commander, the tide had turned on the Confederacy and its disadvantages were too large to overcome. With his forces plagued by disease, desertion, and casualties, Lee abandoned Richmond on April 2, 1865. He hoped to move southwest and join Johnston’s troops in North Carolina. But his forces were soon surrounded by Ulysses S. Grant’s at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered.

Following the war, Lee wasn’t arrested or even punished, though he did lose some property and the right to vote. He supported Reconstruction but opposed some of the measures taken against the South. Though they’d lost the war, Lee was still a popular figure in the South. And after accepting an invitation to visit President Ulysses S. Grant at the White House in 1869, he was a symbol of the reconciliation between North and South. Lee hoped to retire to a farm and live a quiet a life, but he was too famous.

In 1865, Lee was made president of Washington College, and remained in that role until his death. Under Lee’s direction, the university offered the first college courses in business and journalism in the United States. He invited students from the North to aid in reconciliation and was well liked by staff and students alike. The school was later renamed Washington and Lee University to honor him as well as our first president.

In September 1870, Lee suffered a stroke. Two weeks later, he died on October 12, 1870 in Lexington, Virginia. He was buried underneath Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University. By the end of the century, he was popular in the North as well as the South, many respecting his devotion to duty and military brilliance.

U.S. #2975b

1995 32¢ Robert E. Lee

Civil War

- Issued for the 130th anniversary of the Civil War

- From the second pane in the Classic Collections Series

- Declared the most popular stamps of 1995 by the USPS

Stamp Category: Commemorative

Set: Civil War 130th Anniversary

Value: 32¢, rate for first-class mail

First Day of Issue: June 29, 1995

First Day City: Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Quantity Issued: 15,000,000

Printed by: Stamp Venturers

Printing Method: Photogravure

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 120

Perforations: 10.1

Why the stamp was issued: To mark the 130th anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

About the stamp design: The Civil War stamps featured artwork by Mark Hess, who had previously produced the artwork for the Legends of the West sheet. The USPS explained that they liked his painting style because of its “folksy stiffness,” that “emulates people standing uncomfortably in front of daguerreotype cameras.”

According to Hess, his portrait of Robert E. Lee was in “the grand manner style of painting.” He wanted to “show Lee as an incredibly proud, heroic figure…. That was appropriate to his character.” He depicted Lee in his field uniform with his colonel’s stars (rather than his dress uniform which would have carried his general’s wreath. Behind Lee, his horse Traveller is rearing while being handled by an aide with dark clouds, smoke, and fire in the background.

First Day City: The official first day ceremony was held at the Gettysburg National Military Park in Pennsylvania, the site of one of the war’s most famous battles. Because they received a large number of requests, the USPS made the stamps available for sale across the country the same day.

Unusual facts about the Civil War stamps: The Civil War sheet was available by mail order in uncut press sheets of six panes. Of these, 20,000 were signed by stamp artist Mark Hess. The USPS also produced a set of postcards featuring the same images as the stamps (US #UX200-19). Imperforate and partially imperforate error panes have also been found.

About the Civil War Stamps: The Civil War stamp sheet featured 16 individuals – eight from the Union and eight from the Confederacy. The four battles in the corners included one victory for each side and two that are considered draws.

This was the second sheet in the Classic Collections Series following the famed Legends of the West sheet. Stamps in this series follow a similar format – 20 stamps, a decorative header, and information about each stamp printed on its back under the gum.

Plans for the Civil War sheet began while the 1994 Legends of the West sheet was still in its planning stage. The USPS believed that the Civil War was a natural addition to the new series and would be informational for the public. Initially the Citizens Stamp Advisory Committee rejected the idea, saying they should wait 20 years for the 50th anniversary of the war. But they were eventually swayed and the Civil War stamps were created. A group of historians were tasked with making a list of protentional subjects and Shelby Foote was hired to make the final selections. Foote was an expert in the Civil War, having written a three-volume history of the war and been featured in Ken Burns’ PBS documentary series on the war.

The USPS wanted the Civil War stamps to have more action to them – so only the two presidents were depicted in traditional portraits. The rest of the individuals were placed in the field or amidst an activity. After the Legends of the West mix-up, in which the Bill Pickett stamp mistakenly pictured his brother Ben, the USPS completely revamped their research process. The release of the 20 Civil War stamps marked the most extensive effort in the history of the USPS to review and verify the historical accuracy of stamp subjects. As Hess completed each version of his paintings, they were sent to a panel of experts who commented on the historical accuracy of everything from the weather to belt buckles.

Some of the people and battles featured in the Civil War sheet had appeared on US stamps before. This was also the second time the Civil War was honored – a set of five stamps (US #1178-82) was issued for the centennial in the 1960s. And from 2011-15, the USPS issued a series of stamps for the war’s 150th anniversary (US #4522/4981).

History the stamp represents: Descended from one of Virginia’s first families, Robert E. Lee was born on January 19, 1807, in Stratford Hall, Virginia. He was the son of Revolutionary War hero Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee.

Lee’s father’s unfortunate financial choices and early death left his widow with several children and little money. However, a relative helped secure Robert’s appointment to West Point, where he graduated second in his class without incurring any demerits during his four years of study.

In June 1829, Lee was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers and sent to build a fort in the Savannah River. This assignment was followed by a stint at Fort Monroe, Virginia. During the summer of 1829, Lee began courting Martha Washington’s great-granddaughter, Mary Custis, who had also captured the attention of Sam Houston (who would eventually become a southern governor opposed to secession). Robert and Mary were wed on June 30, 1831, at Custis’ home at Arlington House.

Lee continued his military career and was often stationed at remote outposts. Although she had been raised in an affluent household with servants, Mary chose to accompany her husband much of the time. Eventually, she was forced to remain at Arlington due to the birth of seven children and her declining health.

Lee distinguished himself during the Mexican-American War, where he was one of Winfield Scott’s chief aides and met Ulysses S. Grant. After the war, Lee was stationed closer to home and was appointed Superintendent of West Point in 1852.

As the slavery debate ignited, President James Buchanan gave Lee command of a detachment to suppress John Brown and retake the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. Lee described Brown as a “fanatic or madman.”

When Texas seceded in February 1861, General David E. Twiggs surrendered all American forces under his command, which included Lee, to the Texans. Lee returned to the capital and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of Cavalry, an order that was signed by Lincoln. He was promoted to colonel on March 28, turning down an offer to command the Confederate Army. However, Lincoln’s call for troops to put down the rebellion was the catalyst for Virginia’s secession, and Lee’s first duty was to his state.

As dawn approached on April 20, 1861, Robert E. Lee penned a letter to a relative. “I have been unable to make up my mind to raise my hand against my native state, my relations, my children, and my home.” Moments earlier, Lee had sent a letter to the War Department announcing his resignation and ending a distinguished 32-year U.S. military career.

Lee’s decision was astounding. His ancestors included some of the nation’s greatest patriots. A day earlier, as events unfolded following the attack on Fort Sumter, Lee had been offered command of the volunteers defending the nation’s capital.

As war became certain, the Lee clan was forced to take sides. Lee’s wife and sister were devout Unionists, while his daughter believed firmly in secession. The general’s brothers remained faithful to their military oaths, as did his cousins. Lee opposed secession but his sense of duty to Virginia was stronger.

After resigning from the U.S. Army on April 20, Lee took command of the Virginia state forces three days later. Fearing for his wife’s safety – Arlington House was directly across the Potomac River from the nation’s capital – Lee convinced Mary to vacate their home. Federal troops quickly seized the mansion. Mary would return for a brief visit several years later, but Robert E. Lee never saw his home again.

Lee was named one of the Confederate Army’s first five full generals. Soon after, he was defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain and widely credited with causing the loss. After General Joseph E. Johnston’s wounding at the Battle of Seven Pines, Lee took command of the Army of Northern Virginia. His aggressive tactics unnerved Union General George McClellan, leading to a string of decisive Union defeats and a turnaround in public opinion.

A string of Confederate victories followed – Chancellorsville, Cold Harbor, Fredericksburg, Spotsylvania, The Wilderness, Seven Days Battles, and Second Manassas. Lee fought McClellan to a draw at Antietam. But by 1863, the Confederate fronts were crumbling in the West. His invasion of Pennsylvania, which was partly to seize urgently needed supplies for his desperate troops, ended with a crushing defeat at Gettysburg.

Although Lee was a brilliant tactician and a daring battlefield commander, the tide had turned on the Confederacy and its disadvantages were too large to overcome. With his forces plagued by disease, desertion, and casualties, Lee abandoned Richmond on April 2, 1865. He hoped to move southwest and join Johnston’s troops in North Carolina. But his forces were soon surrounded by Ulysses S. Grant’s at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered.

Following the war, Lee wasn’t arrested or even punished, though he did lose some property and the right to vote. He supported Reconstruction but opposed some of the measures taken against the South. Though they’d lost the war, Lee was still a popular figure in the South. And after accepting an invitation to visit President Ulysses S. Grant at the White House in 1869, he was a symbol of the reconciliation between North and South. Lee hoped to retire to a farm and live a quiet a life, but he was too famous.

In 1865, Lee was made president of Washington College, and remained in that role until his death. Under Lee’s direction, the university offered the first college courses in business and journalism in the United States. He invited students from the North to aid in reconciliation and was well liked by staff and students alike. The school was later renamed Washington and Lee University to honor him as well as our first president.

In September 1870, Lee suffered a stroke. Two weeks later, he died on October 12, 1870 in Lexington, Virginia. He was buried underneath Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University. By the end of the century, he was popular in the North as well as the South, many respecting his devotion to duty and military brilliance.