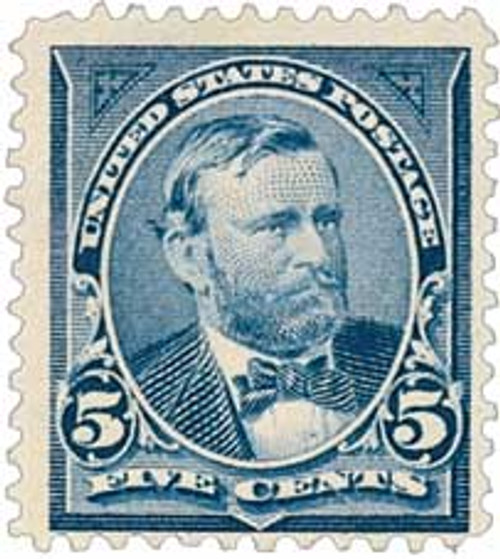

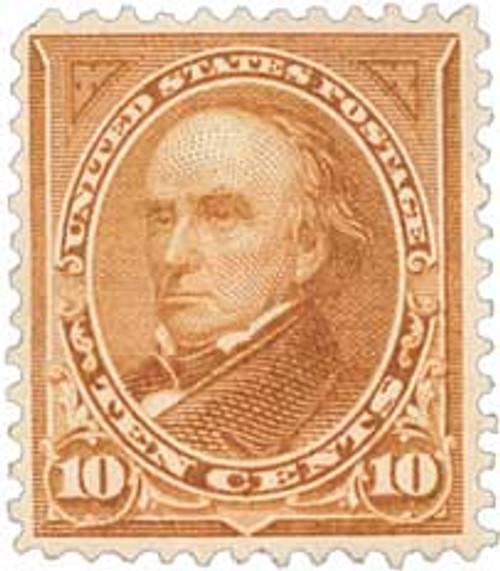

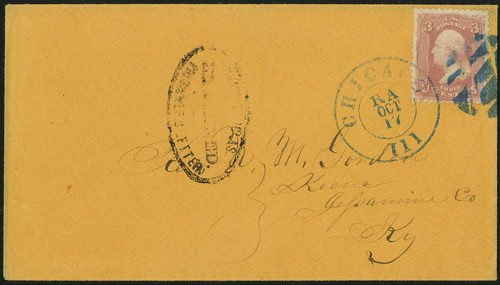

# 281 - 1898 5c Grant, dark blue

Series of 1898-99 5¢ Grant

Universal Postal Union Colors

Issue Quantity: 279,622,170

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Dark blue

U.S. #281 was issued as a direct result of the recommendations of the Universal Postal Union. The organization was formed in 1874 to standardize and simplify the international mailing system. At its 1898 Congress, the UPU recommended blue ink for all stamps issued by participating members to satisfy the international single letter rate. U.S. #281 was also overprinted for use in Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. In 1903, U.S. #281 was replaced by the 5¢ Series of 1902 stamp.

Battle Of Fort Henry

Though Kentucky had declared its neutrality in early 1861, Confederates entered the state that September. They occupied the town of Columbus, taking control of the strategic Tennessee River. They installed large guns, placed underwater mines, and stationed 17,000 troops there. This effectively cut off northern shipping to the south.

Days later, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant seized Paducah, Kentucky, which was an important transportation hub on the Tennessee River. This squashed the Confederate advantage. By early 1862, the Confederate forces were spread too thin over a long defensive line spreading from Arkansas to the Cumberland Gap.

Meanwhile, President Lincoln was pushing for a large offensive by George Washington’s birthday. Serving under Major General Henry Halleck, Grant suggested moving against Fort Henry. Located along the Tennessee-Kentucky border, the fort was manned by about 4,000 Confederates. Halleck approved the plan on January 30. By February 5, Grant had nearly 17,000 men in two divisions plus the Western Gunboat Flotilla ready to strike. The flotilla, commanded by Andrew Hull Foote, had four ironclad gunboats and three wooden gunboats.

In preparation for the battle, Grant landed his divisions in two different locations – one three miles north of the fort along the east bank of the river to prevent the Confederates from escaping. The other division would capture nearby Fort Heiman and use its artillery against Fort Henry.

However, on the night of February 5, as Grant’s men got into place, they were slowed by heavy rain. The infantry wouldn’t reach their positions in time to fight, leaving the naval force to lead the battle on their own. The gunboats got into position around the fort at about 12:30 pm on February 6 and began firing shortly after. They exchanged fire with the fort’s few guns for over an hour. The Union troops then called for the Confederates to surrender, but they refused, so the firing continued. After 75 minutes of fighting, the Confederate commander in charge of the fort, Lloyd Tilghman, ordered his men to raise the white flag and surrender. Tilghman was then imprisoned and later exchanged.

Grant and his men finally arrived at the fort at about 3 pm on February, after the surrender. Following the victory, Grant sent a message to Halleck saying, “Fort Henry is ours… I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry.” Halleck, in turn, sent a message to Washington, DC: “Fort Henry is ours. The flag is reestablished on the soil of Tennessee. It will never be removed.” One newspaper of the day declared the battle was “one of the most complete and signal victories in the annals of the world’s warfare.”

The Union success at Fort Henry was important – it opened up the Tennessee River to Union gunboats and allowed for shipping south of the Alabama border. As promised, Grant captured Fort Donelson later in the month, opening up the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers for Union use, to transport men and supplies.

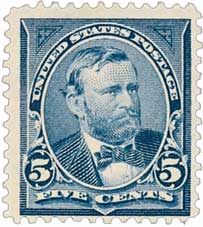

Series of 1898-99 5¢ Grant

Universal Postal Union Colors

Issue Quantity: 279,622,170

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Dark blue

U.S. #281 was issued as a direct result of the recommendations of the Universal Postal Union. The organization was formed in 1874 to standardize and simplify the international mailing system. At its 1898 Congress, the UPU recommended blue ink for all stamps issued by participating members to satisfy the international single letter rate. U.S. #281 was also overprinted for use in Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. In 1903, U.S. #281 was replaced by the 5¢ Series of 1902 stamp.

Battle Of Fort Henry

Though Kentucky had declared its neutrality in early 1861, Confederates entered the state that September. They occupied the town of Columbus, taking control of the strategic Tennessee River. They installed large guns, placed underwater mines, and stationed 17,000 troops there. This effectively cut off northern shipping to the south.

Days later, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant seized Paducah, Kentucky, which was an important transportation hub on the Tennessee River. This squashed the Confederate advantage. By early 1862, the Confederate forces were spread too thin over a long defensive line spreading from Arkansas to the Cumberland Gap.

Meanwhile, President Lincoln was pushing for a large offensive by George Washington’s birthday. Serving under Major General Henry Halleck, Grant suggested moving against Fort Henry. Located along the Tennessee-Kentucky border, the fort was manned by about 4,000 Confederates. Halleck approved the plan on January 30. By February 5, Grant had nearly 17,000 men in two divisions plus the Western Gunboat Flotilla ready to strike. The flotilla, commanded by Andrew Hull Foote, had four ironclad gunboats and three wooden gunboats.

In preparation for the battle, Grant landed his divisions in two different locations – one three miles north of the fort along the east bank of the river to prevent the Confederates from escaping. The other division would capture nearby Fort Heiman and use its artillery against Fort Henry.

However, on the night of February 5, as Grant’s men got into place, they were slowed by heavy rain. The infantry wouldn’t reach their positions in time to fight, leaving the naval force to lead the battle on their own. The gunboats got into position around the fort at about 12:30 pm on February 6 and began firing shortly after. They exchanged fire with the fort’s few guns for over an hour. The Union troops then called for the Confederates to surrender, but they refused, so the firing continued. After 75 minutes of fighting, the Confederate commander in charge of the fort, Lloyd Tilghman, ordered his men to raise the white flag and surrender. Tilghman was then imprisoned and later exchanged.

Grant and his men finally arrived at the fort at about 3 pm on February, after the surrender. Following the victory, Grant sent a message to Halleck saying, “Fort Henry is ours… I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry.” Halleck, in turn, sent a message to Washington, DC: “Fort Henry is ours. The flag is reestablished on the soil of Tennessee. It will never be removed.” One newspaper of the day declared the battle was “one of the most complete and signal victories in the annals of the world’s warfare.”

The Union success at Fort Henry was important – it opened up the Tennessee River to Union gunboats and allowed for shipping south of the Alabama border. As promised, Grant captured Fort Donelson later in the month, opening up the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers for Union use, to transport men and supplies.