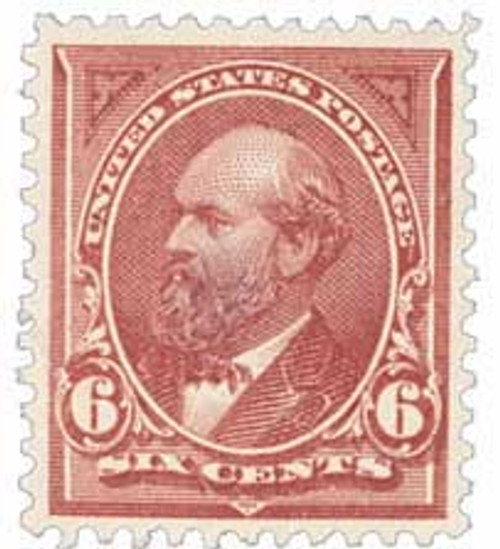

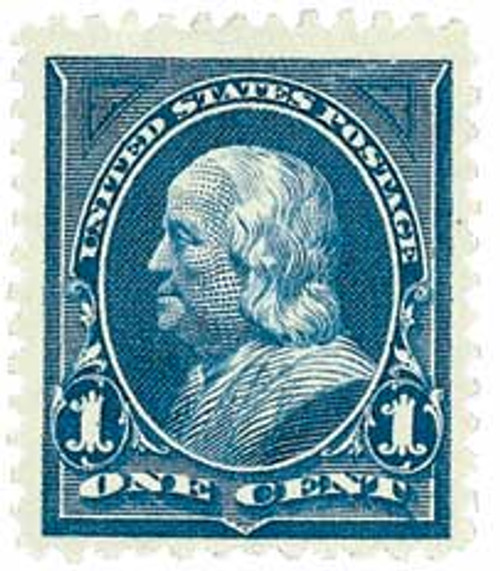

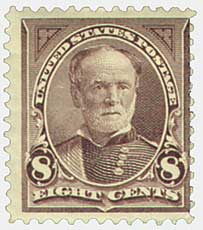

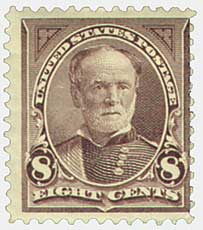

# 272 - 1895 8c Sherman, double line watermark

1895 8¢ Sherman

Issue Quantity: 96,217,820

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Violet brown

The most common use of U.S. #272 was to pay the Registration fee. It was replaced on December 2, 1902, with the Series of 1902 issue.

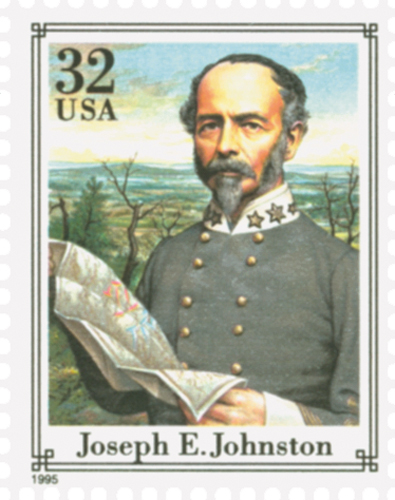

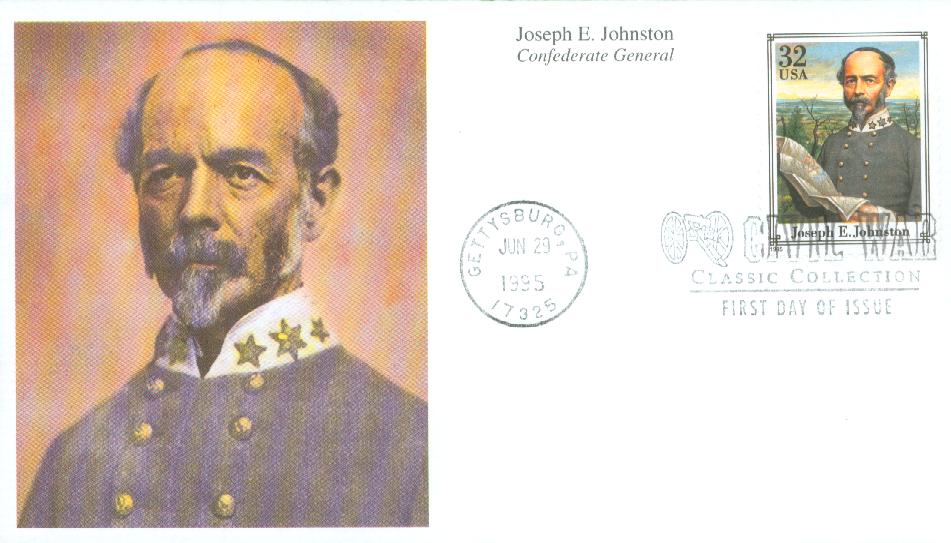

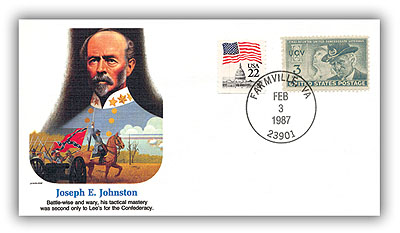

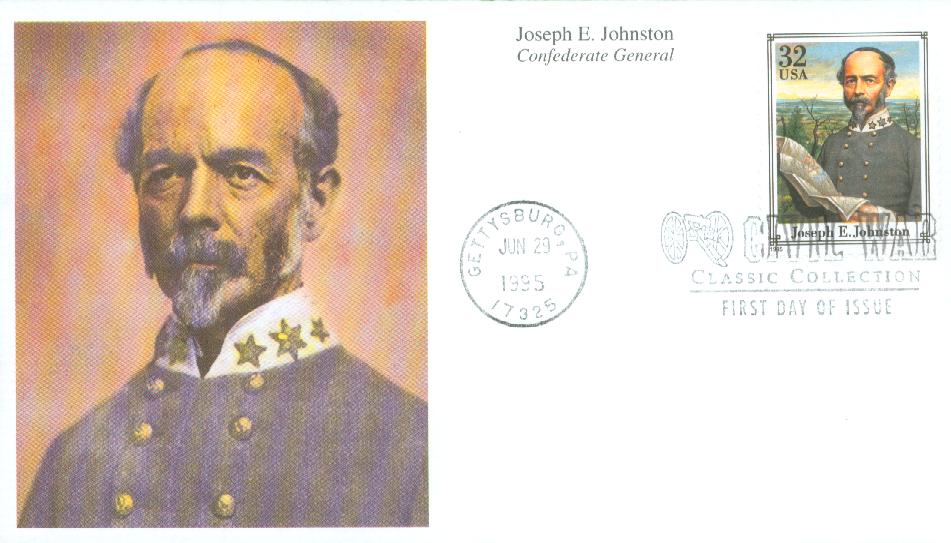

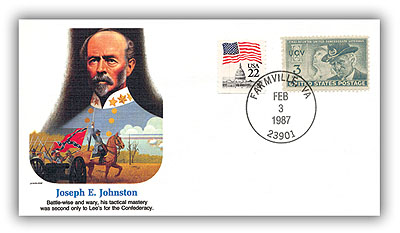

Death Of General Joseph E. Johnston

Johnston was born on February 3, 1807, in Farmville, Virginia. He was named for Major Joseph Eggleston, the Revolutionary War captain his father once served with under the command of “Lighthorse Harry” Henry Lee. His great-uncle was Patrick Henry.

With these connections, Johnston was appointed to West Point in 1825, where he trained as a civil engineer. Service in the Black Hawk, Second Seminole, and Mexican-American Wars followed. During his early career, Johnston became a close friend and mentor of George McClellan. In 1860, Johnston was promoted to brigadier general and named quartermaster of the U.S. Army.

Johnston opposed secession. However, he resigned his U.S. Army commission in April 1861 when his home state of Virginia joined the Confederacy. As a brigadier general and quartermaster general of the U.S. Army, Joseph Johnston was the highest-ranking Federal officer to defect to the Confederacy. Johnston then joined the Confederate army and was appointed brigadier general. His first responsibility was to command forces at Harpers Ferry.

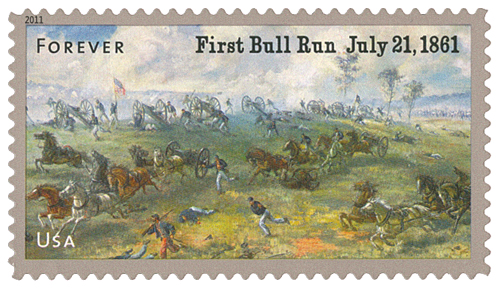

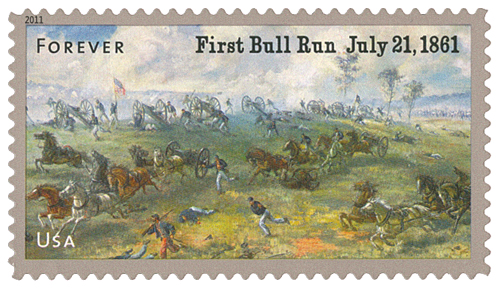

Shortly after the war began in earnest, Johnston reinforced General P.G.T. Beauregard and scored a complete victory over Union forces at the First Battle of Bull Run. Johnston was promoted to general for his role in the rout, but earned the wrath of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who faulted him for not pursuing the Union Army as they fled the battlefield. Although he had been the most senior officer to join the rebel cause, Johnston’s Confederate rank of general placed him beneath three others.

In spite of the animosity with Davis, Johnston led the Confederate Army of the Potomac during 1862 Peninsula Campaign. On May 31, he prevented McClellan’s advance at the Battle of Seven Pines but was badly wounded. During Johnston’s lengthy recovery, Robert E. Lee was placed in charge and drove McClellan from Virginia.

In the fall of 1862, Johnston was placed in command of the Western Theater where forces under Ulysses S. Grant were threatening to take Mississippi. Johnston evacuated the state capital of Jackson and tried to join General John C. Pemberton, who was attempting to hold the important Mississippi River city of Vicksburg. Because of Grant’s overwhelming advantage, Johnston ordered Pemberton to relinquish control of the city. Davis, however, directed Pemberton to hold the city at all cost. Pemberton’s army was forced to surrender on July 4, 1863, giving the Union control of Vicksburg.

Although he was widely criticized for his actions in Mississippi, Johnston replaced General Braxton Bragg and was given control of the Army of Tennessee. His mission was to stop General William T. Sherman’s march to Atlanta. Again, Johnston tried to preserve his army by retreating strategically. Although he was victorious at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Johnston wasn’t able to stop Sherman’s advance. Davis replaced him with General John Bell, eventually ordering Johnston to command the Army of Tennessee in North Carolina. Johnston’s troops were defeated at the Battle of Bentonville in March 1865 and surrendered after learning Lee had done the same at Appomattox.

Johnston made his home in Savannah, Georgia, after the war. He worked as an insurance agent and railroad president. A few years later, Johnston wrote his memoirs and moved to Richmond. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives for a single term before being appointed U.S. commissioner of railroads by President Grover Cleveland.

In February 1891, Johnston served as a pallbearer for his former adversary, Sherman. As a show of respect, Johnston stood at attention in the cold rain without a hat during the service. “If I were in his place and he were standing here in mine, he would not put on his hat,” he told a concerned friend. Johnston caught cold that day, developed pneumonia, and died a few weeks later on March 21, 1891.

1895 8¢ Sherman

Issue Quantity: 96,217,820

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Watermark: Double line USPS

Perforation: 12

Color: Violet brown

The most common use of U.S. #272 was to pay the Registration fee. It was replaced on December 2, 1902, with the Series of 1902 issue.

Death Of General Joseph E. Johnston

Johnston was born on February 3, 1807, in Farmville, Virginia. He was named for Major Joseph Eggleston, the Revolutionary War captain his father once served with under the command of “Lighthorse Harry” Henry Lee. His great-uncle was Patrick Henry.

With these connections, Johnston was appointed to West Point in 1825, where he trained as a civil engineer. Service in the Black Hawk, Second Seminole, and Mexican-American Wars followed. During his early career, Johnston became a close friend and mentor of George McClellan. In 1860, Johnston was promoted to brigadier general and named quartermaster of the U.S. Army.

Johnston opposed secession. However, he resigned his U.S. Army commission in April 1861 when his home state of Virginia joined the Confederacy. As a brigadier general and quartermaster general of the U.S. Army, Joseph Johnston was the highest-ranking Federal officer to defect to the Confederacy. Johnston then joined the Confederate army and was appointed brigadier general. His first responsibility was to command forces at Harpers Ferry.

Shortly after the war began in earnest, Johnston reinforced General P.G.T. Beauregard and scored a complete victory over Union forces at the First Battle of Bull Run. Johnston was promoted to general for his role in the rout, but earned the wrath of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who faulted him for not pursuing the Union Army as they fled the battlefield. Although he had been the most senior officer to join the rebel cause, Johnston’s Confederate rank of general placed him beneath three others.

In spite of the animosity with Davis, Johnston led the Confederate Army of the Potomac during 1862 Peninsula Campaign. On May 31, he prevented McClellan’s advance at the Battle of Seven Pines but was badly wounded. During Johnston’s lengthy recovery, Robert E. Lee was placed in charge and drove McClellan from Virginia.

In the fall of 1862, Johnston was placed in command of the Western Theater where forces under Ulysses S. Grant were threatening to take Mississippi. Johnston evacuated the state capital of Jackson and tried to join General John C. Pemberton, who was attempting to hold the important Mississippi River city of Vicksburg. Because of Grant’s overwhelming advantage, Johnston ordered Pemberton to relinquish control of the city. Davis, however, directed Pemberton to hold the city at all cost. Pemberton’s army was forced to surrender on July 4, 1863, giving the Union control of Vicksburg.

Although he was widely criticized for his actions in Mississippi, Johnston replaced General Braxton Bragg and was given control of the Army of Tennessee. His mission was to stop General William T. Sherman’s march to Atlanta. Again, Johnston tried to preserve his army by retreating strategically. Although he was victorious at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Johnston wasn’t able to stop Sherman’s advance. Davis replaced him with General John Bell, eventually ordering Johnston to command the Army of Tennessee in North Carolina. Johnston’s troops were defeated at the Battle of Bentonville in March 1865 and surrendered after learning Lee had done the same at Appomattox.

Johnston made his home in Savannah, Georgia, after the war. He worked as an insurance agent and railroad president. A few years later, Johnston wrote his memoirs and moved to Richmond. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives for a single term before being appointed U.S. commissioner of railroads by President Grover Cleveland.

In February 1891, Johnston served as a pallbearer for his former adversary, Sherman. As a show of respect, Johnston stood at attention in the cold rain without a hat during the service. “If I were in his place and he were standing here in mine, he would not put on his hat,” he told a concerned friend. Johnston caught cold that day, developed pneumonia, and died a few weeks later on March 21, 1891.