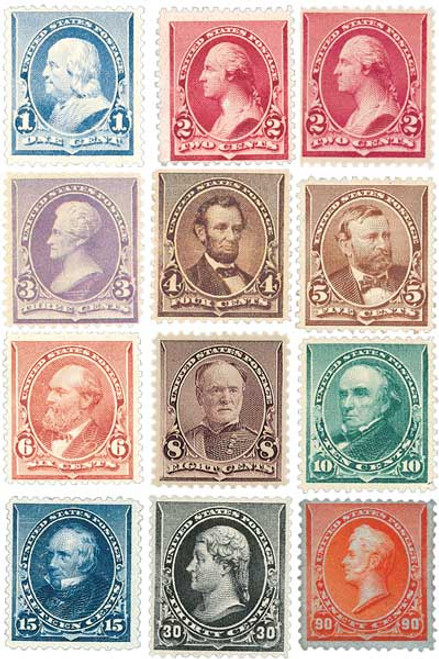

# 224 - 1890 6c Garfield, brown red

1890-93 Regular Issue 6¢ Garfield

Issue Date: February 22, 1890

Issue Quantity: 9,253,400

Printed by: American Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Red Brown

President James A. Garfield

The last of the “log cabin Presidents,” James A. Garfield was born November 19, 1831, near Cleveland, Ohio, to impoverished farmers.

The youngest of five children, Garfield lost his father just two years later and spent much of his childhood working on the family farm to support his near-penniless mother.

As a student at the Geauga Academy, Garfield worked as a carpenter and part-time teacher, discovering his love for learning and teaching. Beginning in 1851, Garfield studied at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later renamed Hiram College), while working as a school janitor. While there, he took great interest in the Greek and Latin languages. Garfield graduated with honors in 1856 and went on to teach classical languages, English, history, geology, and math at his former school, the Eclectic Institute. The following year, he began a four-year stint as president of the school but grew tired of the faculty arguing.

In 1858 Garfield became the Ohio State legislature’s youngest member. During his service in the legislature, Garfield was key in the formation of a bill creating Ohio’s first geological survey measuring mineral sources. He studied law on his own and passed the Ohio bar exam in 1861.

As the slavery debate led to the Civil War, Garfield, an abolitionist, strongly opposed its spreading into the Western territories. By mid-August 1861, he organized the 42nd Ohio Infantry. One of his first tasks was to drive Confederate forces from eastern Kentucky. This success brought him early notoriety and promotion to brigadier general just two days later. Garfield later served with distinction at the Battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh, Corinth, and Chickamauga.

Garfield was elected to the House of Representatives in November 1862, even though he hadn’t campaigned for the position. He was reluctant to take the role at first but believed his abilities would be put to better use there than on the battlefield. Within a year he resigned his position in the Army and took his seat in the House of Representatives.

While Garfield had previously campaigned for President Lincoln, he didn’t particularly like him. However, when riots broke out on New York’s Wall Street over the news of Lincoln’s assassination, Garfield delivered an eloquent speech that calmed the crowd. This is often considered one of the most notable moments of his career.

Garfield spent a total of nine terms in the House of Representatives. Gaining a detailed knowledge of financial matters, Garfield served on several important committees and held multiple positions including chairman of the Banking and Currency Committee, the Appropriations Committee, and the Military Affairs Committee. As a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, he supported hard money policies, in contradiction with his district. He refused to support any legislation that would increase the money supply by issuing paper currency without the proper amount of gold to back it up.

At the Republican Convention of 1880, three men were in the running for the presidential nomination – former President Ulysses S. Grant, Maine Senator James G. Blaine, and Treasury Secretary John Sherman, who Garfield supported. The convention was deadlocked through the first 33 rounds of voting. In that time, Garfield had received a couple of courtesy votes each round. On the next ballot he received 16, then 50 on the following vote. Although he had been elected to the US Senate prior to the Convention, by days end, Garfield secured the Republican presidential nomination with 399 votes to Grant’s 306.

With Chester A. Arthur as his running mate, Garfield won one of the closest elections on record, by just 7,368 votes. This made him the only person to be elected to the presidency directly from the House of Representatives. Also for a short time, he was a sitting Representative, Senator-elect, and President-elect. The following spring, Garfield’s mother was the first President’s mother to attend her son’s inauguration. When his mother was living in the White House throughout his term, President Garfield personally carried her up the stairs.

Much of Garfield’s time in office was spent appointing the collectorship of the Port of New York. The position was significant because the New York port was the busiest in the country, collecting more revenue than all other US ports combined. He selected William H. Robertson, temporary president of the Senate, a move that outraged some who felt their party would be rewarded with the position. Eventually, they resigned, making Garfield the undisputed party leader.

Calling on his financial expertise from his time in the House, Garfield had the Treasury refinance government bonds, reducing the rate from six to three-and-a-half percent interest. This saved the government $10 million per year, which was four percent of the budget at that time.

The only order Garfield was able to carry out during his administration was giving government workers May 30, 1881, off from work, so they could decorate the graves of those who had died in the Civil War. This was an early predecessor to Memorial Day. President Garfield also called for civil service reform. Although Garfield did not live to see it, his successor, Chester Arthur, passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act that required government jobs be awarded on merit.

Deeply concerned with the rights of African Americans, President Garfield pushed for universal education, funded by the Federal government, to school the 70% illiterate African American population. Despite his efforts, the President failed to get the support of Congress and nothing was done in this matter for several years.

Then, on July 2, 1881, President Garfield was preparing to take his sons to his former school, Williams College. As they entered Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac train station at 9:20 a.m., the President was shot in the back by a .44 British Bulldog revolver. The shooter was Charles J. Guiteau, who specifically selected the gun because he thought it would look impressive in a museum. Guiteau was well known around the capitol as an emotionally disturbed man. He shot the President because he felt slighted when Garfield refused to appoint him as US consul to Paris. The assassin had stalked the President for weeks beforehand.

Doctors were never able to find the bullet, which ended up being lodged in Garfield’s pancreas. More than two months later, on September 19, President Garfield died of blood poisoning and complications from the shooting. On that day, Guiteau wrote a letter to Garfield’s successor, Chester A. Arthur, saying, “My inspiration is a godsend to you and I presume that you appreciate it… Never think of Garfield’s removal as murder. It was an act of God, resulting from a political necessity for which he was responsible.”

The following year, jurors only deliberated for an hour before returning a guilty verdict. Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882, fully believing he had done God’s work.

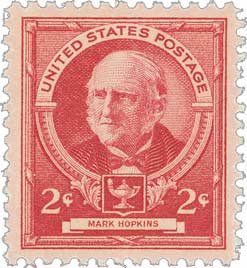

Mark Hopkins was born on February 4, 1802, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He was the youngest college president in the US and produced many influential writings on religion, education, morality, and more. Hopkins was the great-nephew of theologian Samuel Hopkins. He attended Williams College, graduating in 1824. From 1825 to 1827, he was a tutor there. Hopkins also attended Berkshire Medical College in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. After graduating in 1830, he became a professor of moral philosophy and rhetoric at Williams College. Hopkins was asked to be the president of Williams College in 1836 and remained in that position until 1872. When he began his tenure, he was the youngest man to head a college in the US. Williams was a small college where young men could gain an education from teachers who knew their students. Hopkins was loved and respected as a teacher, known for his humor, compassion, and true care for his students. Though he had no formal training in theology, Hopkins was made a Congregationalist minister in 1836. His teachings were greatly influenced by his religious convictions, encouraging piety and moral values as just as, if not more, important than intellectual accomplishments. Throughout his life, Hopkins was a supporter of Christian missions. From 1857 until his death, he served as president of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. In January 1844, Hopkins delivered a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute. Two years later, these lectures were collected as Evidences of Christianity. This became an important and influential textbook that was reprinted several times until 1909. Hopkins had an interest in law, despite no legal training. He used several legal metaphors in Evidences. Hopkins produced many other writings during his life, many of which were based on his lectures and sermons. Some of the most notable were Lectures on Moral Science (1862), The Law of Love and Love as a Law (1869), An Outline Study of Man (1873), The Scriptural Idea of Man (1883), and Teachings and Counsels (1884). Future president James Garfield attended Williams College in the 1850s under Hopkins’s leadership. At an alumni dinner at the White House the day after his inauguration in 1871, Garfield honored Hopkins. “I am not willing that this discussion should close without mention of the value of a true teacher. Give me a log hut, with only a simple bench, Mark Hopkins on one end and I on the other, and you may have all the buildings, apparatus, and libraries without him.” W.E.B. Du Bois later referred to Garfield’s statement in “The Talented Tenth,” saying “There was a time when the American people believed pretty devoutly that a log of wood with a boy at one end and Mark Hopkins at the other, represented the highest ideal of human training. But in these eager days it would seem that we have changed all that and think it necessary to add a couple of saw-mills and a hammer to this outfit, and, at a pinch, to dispense with the services of Mark Hopkins.”Birth of Mark Hopkins

Hopkins resigned from Williams College in 1872 and spent his final years lecturing, teaching, and writing. He died on June 17, 1887.

1890-93 Regular Issue 6¢ Garfield

Issue Date: February 22, 1890

Issue Quantity: 9,253,400

Printed by: American Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Red Brown

President James A. Garfield

The last of the “log cabin Presidents,” James A. Garfield was born November 19, 1831, near Cleveland, Ohio, to impoverished farmers.

The youngest of five children, Garfield lost his father just two years later and spent much of his childhood working on the family farm to support his near-penniless mother.

As a student at the Geauga Academy, Garfield worked as a carpenter and part-time teacher, discovering his love for learning and teaching. Beginning in 1851, Garfield studied at the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute (later renamed Hiram College), while working as a school janitor. While there, he took great interest in the Greek and Latin languages. Garfield graduated with honors in 1856 and went on to teach classical languages, English, history, geology, and math at his former school, the Eclectic Institute. The following year, he began a four-year stint as president of the school but grew tired of the faculty arguing.

In 1858 Garfield became the Ohio State legislature’s youngest member. During his service in the legislature, Garfield was key in the formation of a bill creating Ohio’s first geological survey measuring mineral sources. He studied law on his own and passed the Ohio bar exam in 1861.

As the slavery debate led to the Civil War, Garfield, an abolitionist, strongly opposed its spreading into the Western territories. By mid-August 1861, he organized the 42nd Ohio Infantry. One of his first tasks was to drive Confederate forces from eastern Kentucky. This success brought him early notoriety and promotion to brigadier general just two days later. Garfield later served with distinction at the Battles of Middle Creek, Shiloh, Corinth, and Chickamauga.

Garfield was elected to the House of Representatives in November 1862, even though he hadn’t campaigned for the position. He was reluctant to take the role at first but believed his abilities would be put to better use there than on the battlefield. Within a year he resigned his position in the Army and took his seat in the House of Representatives.

While Garfield had previously campaigned for President Lincoln, he didn’t particularly like him. However, when riots broke out on New York’s Wall Street over the news of Lincoln’s assassination, Garfield delivered an eloquent speech that calmed the crowd. This is often considered one of the most notable moments of his career.

Garfield spent a total of nine terms in the House of Representatives. Gaining a detailed knowledge of financial matters, Garfield served on several important committees and held multiple positions including chairman of the Banking and Currency Committee, the Appropriations Committee, and the Military Affairs Committee. As a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, he supported hard money policies, in contradiction with his district. He refused to support any legislation that would increase the money supply by issuing paper currency without the proper amount of gold to back it up.

At the Republican Convention of 1880, three men were in the running for the presidential nomination – former President Ulysses S. Grant, Maine Senator James G. Blaine, and Treasury Secretary John Sherman, who Garfield supported. The convention was deadlocked through the first 33 rounds of voting. In that time, Garfield had received a couple of courtesy votes each round. On the next ballot he received 16, then 50 on the following vote. Although he had been elected to the US Senate prior to the Convention, by days end, Garfield secured the Republican presidential nomination with 399 votes to Grant’s 306.

With Chester A. Arthur as his running mate, Garfield won one of the closest elections on record, by just 7,368 votes. This made him the only person to be elected to the presidency directly from the House of Representatives. Also for a short time, he was a sitting Representative, Senator-elect, and President-elect. The following spring, Garfield’s mother was the first President’s mother to attend her son’s inauguration. When his mother was living in the White House throughout his term, President Garfield personally carried her up the stairs.

Much of Garfield’s time in office was spent appointing the collectorship of the Port of New York. The position was significant because the New York port was the busiest in the country, collecting more revenue than all other US ports combined. He selected William H. Robertson, temporary president of the Senate, a move that outraged some who felt their party would be rewarded with the position. Eventually, they resigned, making Garfield the undisputed party leader.

Calling on his financial expertise from his time in the House, Garfield had the Treasury refinance government bonds, reducing the rate from six to three-and-a-half percent interest. This saved the government $10 million per year, which was four percent of the budget at that time.

The only order Garfield was able to carry out during his administration was giving government workers May 30, 1881, off from work, so they could decorate the graves of those who had died in the Civil War. This was an early predecessor to Memorial Day. President Garfield also called for civil service reform. Although Garfield did not live to see it, his successor, Chester Arthur, passed the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act that required government jobs be awarded on merit.

Deeply concerned with the rights of African Americans, President Garfield pushed for universal education, funded by the Federal government, to school the 70% illiterate African American population. Despite his efforts, the President failed to get the support of Congress and nothing was done in this matter for several years.

Then, on July 2, 1881, President Garfield was preparing to take his sons to his former school, Williams College. As they entered Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac train station at 9:20 a.m., the President was shot in the back by a .44 British Bulldog revolver. The shooter was Charles J. Guiteau, who specifically selected the gun because he thought it would look impressive in a museum. Guiteau was well known around the capitol as an emotionally disturbed man. He shot the President because he felt slighted when Garfield refused to appoint him as US consul to Paris. The assassin had stalked the President for weeks beforehand.

Doctors were never able to find the bullet, which ended up being lodged in Garfield’s pancreas. More than two months later, on September 19, President Garfield died of blood poisoning and complications from the shooting. On that day, Guiteau wrote a letter to Garfield’s successor, Chester A. Arthur, saying, “My inspiration is a godsend to you and I presume that you appreciate it… Never think of Garfield’s removal as murder. It was an act of God, resulting from a political necessity for which he was responsible.”

The following year, jurors only deliberated for an hour before returning a guilty verdict. Guiteau was hanged on June 30, 1882, fully believing he had done God’s work.

Mark Hopkins was born on February 4, 1802, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. He was the youngest college president in the US and produced many influential writings on religion, education, morality, and more. Hopkins was the great-nephew of theologian Samuel Hopkins. He attended Williams College, graduating in 1824. From 1825 to 1827, he was a tutor there. Hopkins also attended Berkshire Medical College in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. After graduating in 1830, he became a professor of moral philosophy and rhetoric at Williams College. Hopkins was asked to be the president of Williams College in 1836 and remained in that position until 1872. When he began his tenure, he was the youngest man to head a college in the US. Williams was a small college where young men could gain an education from teachers who knew their students. Hopkins was loved and respected as a teacher, known for his humor, compassion, and true care for his students. Though he had no formal training in theology, Hopkins was made a Congregationalist minister in 1836. His teachings were greatly influenced by his religious convictions, encouraging piety and moral values as just as, if not more, important than intellectual accomplishments. Throughout his life, Hopkins was a supporter of Christian missions. From 1857 until his death, he served as president of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. In January 1844, Hopkins delivered a series of lectures at the Lowell Institute. Two years later, these lectures were collected as Evidences of Christianity. This became an important and influential textbook that was reprinted several times until 1909. Hopkins had an interest in law, despite no legal training. He used several legal metaphors in Evidences. Hopkins produced many other writings during his life, many of which were based on his lectures and sermons. Some of the most notable were Lectures on Moral Science (1862), The Law of Love and Love as a Law (1869), An Outline Study of Man (1873), The Scriptural Idea of Man (1883), and Teachings and Counsels (1884). Future president James Garfield attended Williams College in the 1850s under Hopkins’s leadership. At an alumni dinner at the White House the day after his inauguration in 1871, Garfield honored Hopkins. “I am not willing that this discussion should close without mention of the value of a true teacher. Give me a log hut, with only a simple bench, Mark Hopkins on one end and I on the other, and you may have all the buildings, apparatus, and libraries without him.” W.E.B. Du Bois later referred to Garfield’s statement in “The Talented Tenth,” saying “There was a time when the American people believed pretty devoutly that a log of wood with a boy at one end and Mark Hopkins at the other, represented the highest ideal of human training. But in these eager days it would seem that we have changed all that and think it necessary to add a couple of saw-mills and a hammer to this outfit, and, at a pinch, to dispense with the services of Mark Hopkins.”Birth of Mark Hopkins

Hopkins resigned from Williams College in 1872 and spent his final years lecturing, teaching, and writing. He died on June 17, 1887.