U.S. #2194

1989 $1 Johns Hopkins

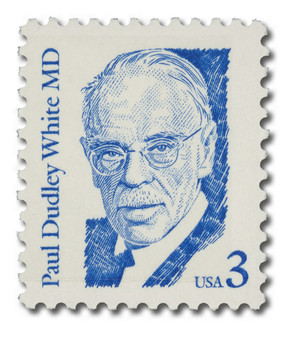

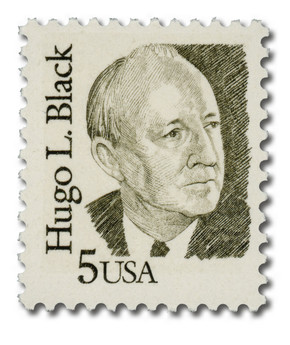

Great Americans

- 45th stamp in Great Americans Series

- Unofficially marks the 100th anniversary of Johns Hopkins Institution

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: Great Americans

Value: $1, for use on registered mail and for “make up” postage on heavier items

First Day of Issue: June 7, 1989

First Day City: Baltimore, Maryland

Quantity Issued: 86,520,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Engraving

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 320

Type: Ex: Type I, II, etc.

Perforations: 11.2 x 11.1

Color: Intense deep blue

Why the stamp was issued: This stamp was issued for use on registered mail and for “make up” postage on heavier items. It replaced the 1986 $1 Bernard Revel stamp, which had stirred controversy after it was discovered it contained a secret mark. This stamp also followed a pattern the USPS had been using for several years, especially within the Great Americans Series – honoring a university with a stamp honoring a person as well. This came about because the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee had instituted a new rule in the 1960s, prohibiting any more stamps honoring specific schools, because there are so many, and some would be bound to be overlooked. So, from time to time, the USPS would issue a stamp picturing a person with a connection to one of these schools in an anniversary year. In this case, Johns Hopkins was featured on a stamp marking the 100th anniversary of the institution which bears his name.

Calls for the stamp began a few years earlier, largely from the institution’s public affairs director and president. They gained support from several Congressmen who had benefitted from surgical techniques pioneered at Johns Hopkins.

About the stamp design: Bradbury Thompson based his stamp portrait on an 1868 John Dabour painting that hangs in the Billings Building at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institution.

First Day City: The First Day ceremony for this stamp was held at the Baltimore Convention Center as part of centennial celebrations of the institution.

Unusual fact about this stamp: A plate flaw resulted in a small number of stamps with the “Lipstick on Shirt Front” – an excess of ink in the middle of Hopkins’ shirt. The flaw was discovered while the stamps were being printed and the plate was corrected, so very few are known to exist.

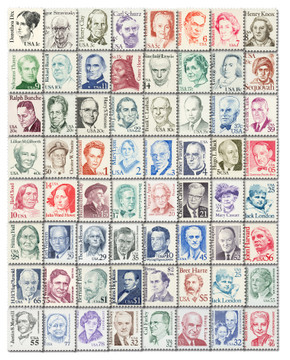

About the Great Americans Series: The Great Americans Series was created to replace the Americana Series. The new series would be characterized by a standard definitive size, simple design, and monochromatic colors.

This simple design included a portrait, “USA,” the denomination, the person’s name, and in some cases, their occupation or reason for recognition. The first stamp in the new series was issued on December 27, 1980. It honored Sequoyah and fulfilled the new international postcard rate that would go into effect in January 1981.

The Great Americans Series would honor a wider range of people than the previous Prominent Americans and Liberty Series. While those series mainly honored presidents and politicians, the Great Americans Series featured people from many fields and ethnicities. They were individuals who were leaders in education, the military, literature, the arts, and human and civil rights. Plus, while the previous series only honored a few women, the Great Americans featured 15 women. This was also the first definitive series to honor Native Americans, with five stamps.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) produced most of the stamps, but private firms printed some. Several stamps saw multiple printings. The result was many different varieties, with tagging being the key to understanding them. Though there were also differences in perforations, gum, paper, and ink color.

The final stamp in the series was issued on July 17, 1999, honoring Justin S. Morrill. Spanning 20 years, the Great Americans was the longest-running US definitive series. It was also the largest series of face-different stamps, with a total of 63.

Click here for all the individual stamps and click here for the complete series.

History the stamp represents: Johns Hopkins was born on May 19, 1795, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Hopkins was named after his grandfather (also Johns Hopkins) who took his mother’s last name (Margaret Johns) as his first when she married Gerard Hopkins.

Hopkins was the second oldest of 11 children in a family of Quakers. After they emancipated their slaves in 1807, Hopkins worked on the farm, forcing him to take a break from his education. When he was 17 Hopkins went to Baltimore to work at his uncle’s grocery business. During the War of 1812, Hopkins’ uncle left him in charge of the shop, giving him the experience he needed to start his own business with Benjamin Moore.

The business was short-lived, leading Hopkins to then go into business with three of his brothers, creating Hopkins & Brothers Wholesalers in 1819. The Hopkins’ traveled the Shenandoah Valley in Conestoga wagons selling a variety of items, accepting corn whiskey as payment from rural families in lieu of money. When he returned to the city, he sold the whiskey as “Hopkins’ Best.” Hopkins also found significant financial success with smart investments, most notably with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). He later served as director of the railroad in 1847 and chairman of its Finance Committee in 1855. Hopkins also served as president of Merchants’ Bank and as the director of several other organizations. His financial successes were so great that he was able to retire in 1847 at the age of 52. But in addition to his business acumen, Hopkins was also extremely charitable. On more than one occasion he donated money to the city of Baltimore during financial crises and twice bailed the railroad out of debt.

Though he was a Maryland native, Hopkins was an avid abolitionist and supported the Union at the outbreak of the Civil War. His summer estate, Clifton, served as a meeting place for Union sympathizers during the war. He was also in frequent contact with President Lincoln, supporting his plans and offering the use of the use of the B&O Railroad for free.

After the war, Hopkins was distraught by the toll it had taken on Baltimore. He was also moved by the yellow fever and cholera epidemics that had killed hundreds in the city several years before. So in 1870, he prepared his will, which set aside $7 million for the creation of a free hospital, medical training colleges, as well as an orphanage and university for African Americans. (This was the largest philanthropic gift in America up to that time.) As Hopkins described it, “I have had many talents given to me and I feel they are in trust. I shall not bury them but give them to the lads who long for a wider education.”

After his death on December 24, 1873, Hopkins’ bequests were set into motion. Per his will, the Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum was to open first, in 1875. At the time, it was home to 24 children. The orphanage was later changed to a training school and later a home for crippled African American children and orphans. It eventually closed in 1924 and never reopened.

Johns Hopkins University was established in 1876, providing both higher education and scientific research. Two years later, the school began printing the Johns Hopkins Press, which is still produced today, making it the longest-running academic press in the country. The university is also frequently placed in the top 10 American colleges.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing opened in 1889 and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine opened in 1893. Together, they form one of the nation’s leading teaching hospitals and biomedical research facilities. A number of medical traditions were begun there, including rounds, residents and house staff. And the hospital developed several medical specialties including neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, pediatrics, and child psychiatry. Today, the hospital is often considered one of the best in the world and was ranked the best in America for 21 consecutive years.

U.S. #2194

1989 $1 Johns Hopkins

Great Americans

- 45th stamp in Great Americans Series

- Unofficially marks the 100th anniversary of Johns Hopkins Institution

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: Great Americans

Value: $1, for use on registered mail and for “make up” postage on heavier items

First Day of Issue: June 7, 1989

First Day City: Baltimore, Maryland

Quantity Issued: 86,520,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Engraving

Format: Panes of 20 in sheets of 320

Type: Ex: Type I, II, etc.

Perforations: 11.2 x 11.1

Color: Intense deep blue

Why the stamp was issued: This stamp was issued for use on registered mail and for “make up” postage on heavier items. It replaced the 1986 $1 Bernard Revel stamp, which had stirred controversy after it was discovered it contained a secret mark. This stamp also followed a pattern the USPS had been using for several years, especially within the Great Americans Series – honoring a university with a stamp honoring a person as well. This came about because the Citizens’ Stamp Advisory Committee had instituted a new rule in the 1960s, prohibiting any more stamps honoring specific schools, because there are so many, and some would be bound to be overlooked. So, from time to time, the USPS would issue a stamp picturing a person with a connection to one of these schools in an anniversary year. In this case, Johns Hopkins was featured on a stamp marking the 100th anniversary of the institution which bears his name.

Calls for the stamp began a few years earlier, largely from the institution’s public affairs director and president. They gained support from several Congressmen who had benefitted from surgical techniques pioneered at Johns Hopkins.

About the stamp design: Bradbury Thompson based his stamp portrait on an 1868 John Dabour painting that hangs in the Billings Building at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institution.

First Day City: The First Day ceremony for this stamp was held at the Baltimore Convention Center as part of centennial celebrations of the institution.

Unusual fact about this stamp: A plate flaw resulted in a small number of stamps with the “Lipstick on Shirt Front” – an excess of ink in the middle of Hopkins’ shirt. The flaw was discovered while the stamps were being printed and the plate was corrected, so very few are known to exist.

About the Great Americans Series: The Great Americans Series was created to replace the Americana Series. The new series would be characterized by a standard definitive size, simple design, and monochromatic colors.

This simple design included a portrait, “USA,” the denomination, the person’s name, and in some cases, their occupation or reason for recognition. The first stamp in the new series was issued on December 27, 1980. It honored Sequoyah and fulfilled the new international postcard rate that would go into effect in January 1981.

The Great Americans Series would honor a wider range of people than the previous Prominent Americans and Liberty Series. While those series mainly honored presidents and politicians, the Great Americans Series featured people from many fields and ethnicities. They were individuals who were leaders in education, the military, literature, the arts, and human and civil rights. Plus, while the previous series only honored a few women, the Great Americans featured 15 women. This was also the first definitive series to honor Native Americans, with five stamps.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) produced most of the stamps, but private firms printed some. Several stamps saw multiple printings. The result was many different varieties, with tagging being the key to understanding them. Though there were also differences in perforations, gum, paper, and ink color.

The final stamp in the series was issued on July 17, 1999, honoring Justin S. Morrill. Spanning 20 years, the Great Americans was the longest-running US definitive series. It was also the largest series of face-different stamps, with a total of 63.

Click here for all the individual stamps and click here for the complete series.

History the stamp represents: Johns Hopkins was born on May 19, 1795, in Anne Arundel County, Maryland. Hopkins was named after his grandfather (also Johns Hopkins) who took his mother’s last name (Margaret Johns) as his first when she married Gerard Hopkins.

Hopkins was the second oldest of 11 children in a family of Quakers. After they emancipated their slaves in 1807, Hopkins worked on the farm, forcing him to take a break from his education. When he was 17 Hopkins went to Baltimore to work at his uncle’s grocery business. During the War of 1812, Hopkins’ uncle left him in charge of the shop, giving him the experience he needed to start his own business with Benjamin Moore.

The business was short-lived, leading Hopkins to then go into business with three of his brothers, creating Hopkins & Brothers Wholesalers in 1819. The Hopkins’ traveled the Shenandoah Valley in Conestoga wagons selling a variety of items, accepting corn whiskey as payment from rural families in lieu of money. When he returned to the city, he sold the whiskey as “Hopkins’ Best.” Hopkins also found significant financial success with smart investments, most notably with the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O). He later served as director of the railroad in 1847 and chairman of its Finance Committee in 1855. Hopkins also served as president of Merchants’ Bank and as the director of several other organizations. His financial successes were so great that he was able to retire in 1847 at the age of 52. But in addition to his business acumen, Hopkins was also extremely charitable. On more than one occasion he donated money to the city of Baltimore during financial crises and twice bailed the railroad out of debt.

Though he was a Maryland native, Hopkins was an avid abolitionist and supported the Union at the outbreak of the Civil War. His summer estate, Clifton, served as a meeting place for Union sympathizers during the war. He was also in frequent contact with President Lincoln, supporting his plans and offering the use of the use of the B&O Railroad for free.

After the war, Hopkins was distraught by the toll it had taken on Baltimore. He was also moved by the yellow fever and cholera epidemics that had killed hundreds in the city several years before. So in 1870, he prepared his will, which set aside $7 million for the creation of a free hospital, medical training colleges, as well as an orphanage and university for African Americans. (This was the largest philanthropic gift in America up to that time.) As Hopkins described it, “I have had many talents given to me and I feel they are in trust. I shall not bury them but give them to the lads who long for a wider education.”

After his death on December 24, 1873, Hopkins’ bequests were set into motion. Per his will, the Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum was to open first, in 1875. At the time, it was home to 24 children. The orphanage was later changed to a training school and later a home for crippled African American children and orphans. It eventually closed in 1924 and never reopened.

Johns Hopkins University was established in 1876, providing both higher education and scientific research. Two years later, the school began printing the Johns Hopkins Press, which is still produced today, making it the longest-running academic press in the country. The university is also frequently placed in the top 10 American colleges.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing opened in 1889 and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine opened in 1893. Together, they form one of the nation’s leading teaching hospitals and biomedical research facilities. A number of medical traditions were begun there, including rounds, residents and house staff. And the hospital developed several medical specialties including neurosurgery, cardiac surgery, pediatrics, and child psychiatry. Today, the hospital is often considered one of the best in the world and was ranked the best in America for 21 consecutive years.