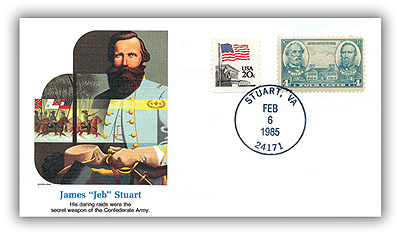

# 20038 - 1985 James Brown Stuart Commemorative Cover

Â

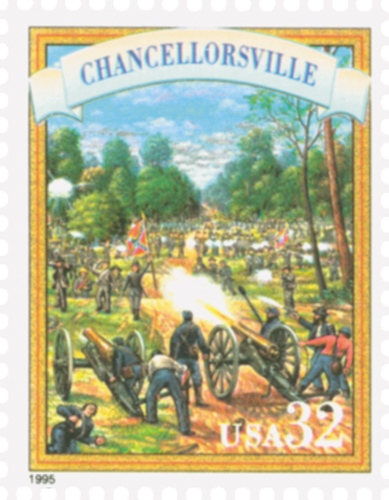

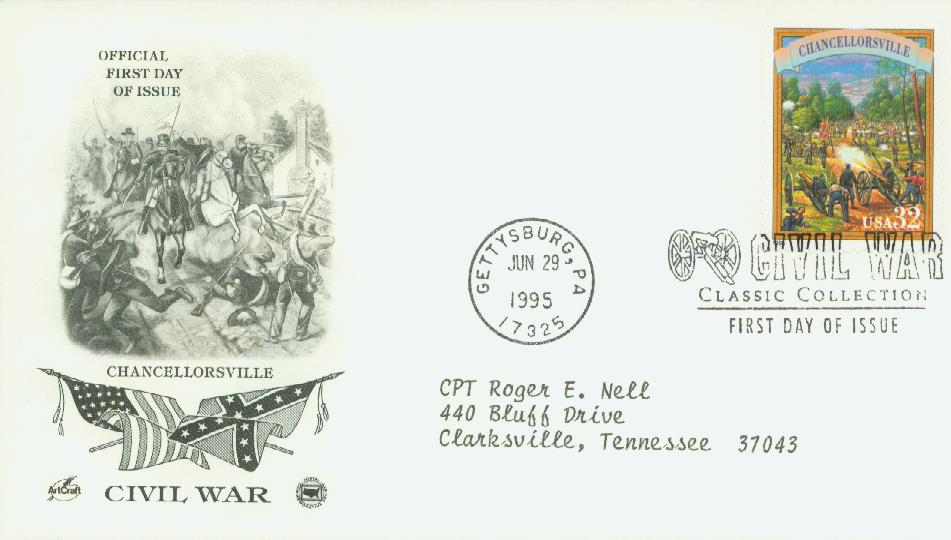

Battle Of ChancellorsvilleÂ

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

On May 6, 1863, the Battle of Chancellorsville ended in a Confederate victory.

Robert E. Lee delivered the Union a stunning defeat at Fredericksburg in December 1862. But Joseph Hooker used the months that followed to reorganize and reinvigorate his troops. Proclaiming he had created “the finest Army on the Planet,†Hooker devised an elaborate plan to turn the left flank of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. The rebel troops, who were outnumbered and starving, were camped near Fredericksburg in the spring of 1863 as Hooker prepared to spring his trap.

Stinging from the heavy losses at Marye’s Heights, Hooker reshaped his troops into a disciplined force with incentives such as better food and a furlough lottery. He centralized his cavalry and beefed up military intelligence under Colonel George H. Sharpe, making him the first in the Potomac army’s history to know what lay ahead of him in a battle.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

What he faced was Robert E. Lee and his army of 61,000 – half the number of Hooker’s force. Lee was fortified behind the Rappahannock, but not in an ideal position. Two divisions under James Longstreet were a distance away, encircling Suffolk in search of supplies, and too far to help once the battle began.

Hooker’s plan was to send all but a few cavalry brigades in a wide circle to the west and south under George Stoneman’s command, moving them to the rear of Lee’s army and cutting his supply lines. While that was happening, two Union corps – nearly equal in size to Lee’s entire army – would pretend an attack in Fredericksburg while the rest of the Army of the Potomac quietly crossed the Rapidan River and into Lee’s left flank. “My plans are perfect. May God have mercy on General Lee for I will have none,†said Hooker.

As the campaign began, communication with Stoneman ended on April 30 but everything else seemed to be going well. As night fell, three Union corps under Henry W. Slocum camped in the region known as the Wilderness, near a tavern called Chancellorsville, resting for the morning’s push eastward.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

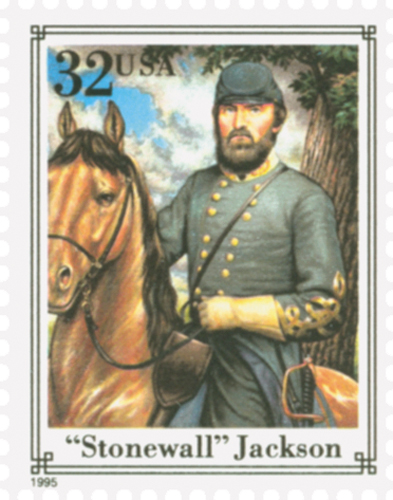

Hooker had intelligence about Lee’s order of battle, but no cavalry to locate the Confederates. As they fumbled in the darkness of the Wilderness’ forest and brambles, the Union troops crashed into Stonewall Jackson’s Second Corps. The day of fighting that followed saw Hooker lose any advantage he had possessed as his men fell back.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Perched on fallen logs, Lee and Jackson plotted strategy late into the night. Facing superior numbers, Lee decided to gamble. Jackson was ordered to march his entire corps twelve miles through the darkness and turn into Hooker’s right, which was vulnerable. Lee would be left with a skeleton force.

Jackson’s troops were spotted the next morning from a Union reconnaissance balloon, but poor communication mangled the message to Hooker. The Union commander decided Lee must have been retreating. Instead, Jackson’s men stormed from the woods late in the afternoon of May 2 to attack the Eleventh Corps. Comprised mostly of German immigrants, the corps earned the nickname the “Flying Dutchmen†for the speed of their retreat.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

As night fell, Jackson and A. P. Hill scouted for a prime location for a second night attack. Both men were hit by friendly fire. Command of the Confederate troops now fell to cavalryman J.E.B. Stuart, who didn’t have orders to work with. Stuart threw his entire force at the Union troops the next morning, resulting in fighting that was as brutal as any in the war.

Multiple attacks were launched throughout the day, causing heavy losses on both sides. As the Second Battle of Fredericksburg was raging nearby, Union General John Sedgwick advanced across the Rappahannock River to defeat the small Confederate force at Marye’s Heights. To counter him, Lee marched a small force east to prevent Sedgwick from reuniting with the rest of the Union Army.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

By May 4, the bloody fighting at Chancellorsville ceased, as Fredericksburg became the focus of the most intense battles. The following day, Sedgwick’s troops retreated north because of a miscommunication compounded by frayed nerves and sheer exhaustion. When he learned the Sixth Corps had retreated, Hooker realized the battle was over and he followed Sedgwick on May 6. The Battle of Chancellorsville is known as Lee’s “perfect battle†because of his risky decision to divide his army in the face of a vastly superior force and then the Confederate victory he achieved. However, this victory was hampered by the death of Stonewall Jackson.

Â

Battle Of ChancellorsvilleÂ

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

On May 6, 1863, the Battle of Chancellorsville ended in a Confederate victory.

Robert E. Lee delivered the Union a stunning defeat at Fredericksburg in December 1862. But Joseph Hooker used the months that followed to reorganize and reinvigorate his troops. Proclaiming he had created “the finest Army on the Planet,†Hooker devised an elaborate plan to turn the left flank of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. The rebel troops, who were outnumbered and starving, were camped near Fredericksburg in the spring of 1863 as Hooker prepared to spring his trap.

Stinging from the heavy losses at Marye’s Heights, Hooker reshaped his troops into a disciplined force with incentives such as better food and a furlough lottery. He centralized his cavalry and beefed up military intelligence under Colonel George H. Sharpe, making him the first in the Potomac army’s history to know what lay ahead of him in a battle.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

What he faced was Robert E. Lee and his army of 61,000 – half the number of Hooker’s force. Lee was fortified behind the Rappahannock, but not in an ideal position. Two divisions under James Longstreet were a distance away, encircling Suffolk in search of supplies, and too far to help once the battle began.

Hooker’s plan was to send all but a few cavalry brigades in a wide circle to the west and south under George Stoneman’s command, moving them to the rear of Lee’s army and cutting his supply lines. While that was happening, two Union corps – nearly equal in size to Lee’s entire army – would pretend an attack in Fredericksburg while the rest of the Army of the Potomac quietly crossed the Rapidan River and into Lee’s left flank. “My plans are perfect. May God have mercy on General Lee for I will have none,†said Hooker.

As the campaign began, communication with Stoneman ended on April 30 but everything else seemed to be going well. As night fell, three Union corps under Henry W. Slocum camped in the region known as the Wilderness, near a tavern called Chancellorsville, resting for the morning’s push eastward.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Hooker had intelligence about Lee’s order of battle, but no cavalry to locate the Confederates. As they fumbled in the darkness of the Wilderness’ forest and brambles, the Union troops crashed into Stonewall Jackson’s Second Corps. The day of fighting that followed saw Hooker lose any advantage he had possessed as his men fell back.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Perched on fallen logs, Lee and Jackson plotted strategy late into the night. Facing superior numbers, Lee decided to gamble. Jackson was ordered to march his entire corps twelve miles through the darkness and turn into Hooker’s right, which was vulnerable. Lee would be left with a skeleton force.

Jackson’s troops were spotted the next morning from a Union reconnaissance balloon, but poor communication mangled the message to Hooker. The Union commander decided Lee must have been retreating. Instead, Jackson’s men stormed from the woods late in the afternoon of May 2 to attack the Eleventh Corps. Comprised mostly of German immigrants, the corps earned the nickname the “Flying Dutchmen†for the speed of their retreat.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

As night fell, Jackson and A. P. Hill scouted for a prime location for a second night attack. Both men were hit by friendly fire. Command of the Confederate troops now fell to cavalryman J.E.B. Stuart, who didn’t have orders to work with. Stuart threw his entire force at the Union troops the next morning, resulting in fighting that was as brutal as any in the war.

Multiple attacks were launched throughout the day, causing heavy losses on both sides. As the Second Battle of Fredericksburg was raging nearby, Union General John Sedgwick advanced across the Rappahannock River to defeat the small Confederate force at Marye’s Heights. To counter him, Lee marched a small force east to prevent Sedgwick from reuniting with the rest of the Union Army.

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

By May 4, the bloody fighting at Chancellorsville ceased, as Fredericksburg became the focus of the most intense battles. The following day, Sedgwick’s troops retreated north because of a miscommunication compounded by frayed nerves and sheer exhaustion. When he learned the Sixth Corps had retreated, Hooker realized the battle was over and he followed Sedgwick on May 6. The Battle of Chancellorsville is known as Lee’s “perfect battle†because of his risky decision to divide his army in the face of a vastly superior force and then the Confederate victory he achieved. However, this victory was hampered by the death of Stonewall Jackson.