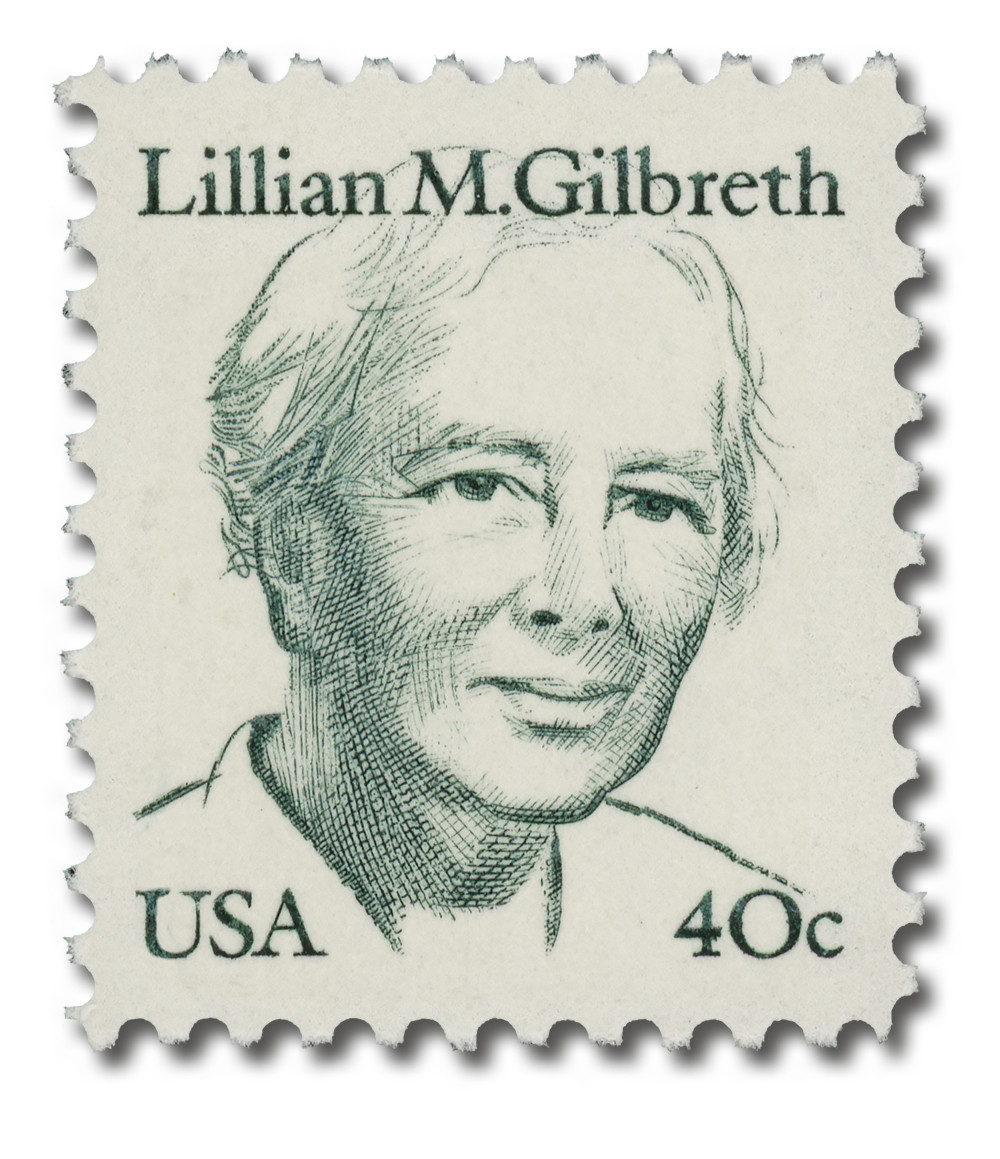

U.S. #1868

1984 40¢ Lillian M. Gilbreth

Great Americans

- 15th stamp in the Great Americans Series

- Honors “America’s first lady of engineering”

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: Great Americans

Value: 40¢; ½-ounce international airmail rate

First Day of Issue: February 24, 1984

First Day City: Montclair, New Jersey

Quantity Issued: 150,000,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving & Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 100

Perforations: 11

Color: Dark green

Why the stamp was issued: This stamp paid the half ounce rate on international airmail.

About the stamp design: Ward Brackett created the portrait on this stamp, based on several photos of Dr. Gilbreth. Interestingly, the USPS first received a suggestion and design for a stamp featuring Dr. Gilbreth in 1982. That year, the National Society for Professional Engineers held a stamp design contest to commemorate their organization’s 50th anniversary. Their winning design depicting Gilbreth was submitted to the USPS, but wasn’t used.

First Day City: The First Day ceremony for this stamp was held at the Student Center of Montclair State College in Montclair, New Jersey, where Gilbreth’s lab was located.

About the Great Americans Series: The Great Americans Series was created to replace the Americana Series. The new series would be characterized by a standard definitive size, simple design, and monochromatic colors.

This simple design included a portrait, “USA,” the denomination, the person’s name, and in some cases, their occupation or reason for recognition. The first stamp in the new series was issued on December 27, 1980. It honored Sequoyah and fulfilled the new international postcard rate that would go into effect in January 1981.

The Great Americans Series would honor a wider range of people than the previous Prominent Americans and Liberty Series. While those series mainly honored presidents and politicians, the Great Americans Series featured people from many fields and ethnicities. They were individuals who were leaders in education, the military, literature, the arts, and human and civil rights. Plus, while the previous series only honored a few women, the Great Americans featured 15 women. This was also the first definitive series to honor Native Americans, with five stamps.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) produced most of the stamps, but private firms printed some. Several stamps saw multiple printings. The result was many different varieties, with tagging being the key to understanding them. Though there were also differences in perforations, gum, paper, and ink color.

The final stamp in the series was issued on July 17, 1999, honoring Justin S. Morrill. Spanning 20 years, the Great Americans was the longest-running US definitive series. It was also the largest series of face-different stamps, with a total of 63.

Click here for all the individual stamps and click here for the complete series.

History the stamp represents: Lillian Evelyn Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24, 1878, in Oakland, California. Dubbed “America’s first lady of engineering,” Gilbreth combined psychology, engineering, and scientific management to improve efficiency and productivity for a number of businesses and industries.

Gilbreth was a bright child, advancing through school grade levels quickly. She was also elected vice president of her senior class in high school. Though Gilbreth’s father objected to her going to college, he agreed to let her try it for a year. Gilbreth finished that year in the top of her class and was permitted to continue her education.

At the University of California, Gilbreth majored in English while also studying philosophy and psychology. She also won a poetry contest and performed in school plays. Graduating in 1900, she was the first woman in the school’s history to give a commencement address. Gilbreth went on to earn a Masters and PhD.

Gilbreth spent her more than 40-year career combining psychology with scientific management and engineering and was a pioneer in the field of industrial and organizational psychology. In this role, she helped engineers to acknowledge the psychological aspects of their work. She introduced the idea of using psychology to study management in 1911 and was the first American engineer to combine psychology and scientific management.

Gilbreth worked with her husband Frank to run Gilbreth, Incorporated, a management consulting and industrial engineering firm. The Gilbreths also wrote several books and over 50 scientific papers together. Among the Gilbreth’s projects were time-and-motion studies. They set up video cameras to record workers and then analyzed those videos to redesign machinery that was more in-tune with workers’ movements.

These changes would also help to increase efficiency and decrease fatigue. The Gilbreths work was a precursor to the field of ergonomics. Other innovations the Gilbreths encouraged were better lighting, regular breaks, suggestion boxes, and free books. They called their program the Gilbreth System with the slogan “The One Best Way to Do Work.” Some of their clients included Macy’s and Johnson & Johnson.

After her husband’s death in 1924, Gilbreth continued to research, write, teach, and consult businesses. She also began exploring how she could apply her research to the home. She “sought to provide women with shorter, simpler, and easier ways of doing housework to enable them to seek paid employment outside the home.” As a result, Gilbreth developed the “work triangle” kitchen layout that is often still used today. She also invented the foot-pedal trash can and wall light switches, and suggested adding shelves to the inside of refrigerator doors, as well as the inclusion of the butter and egg holders. Gilbreth also filed patents for an improvement on the electric can opener and wastewater hose for washing machines.

Throughout her career, Gilbreth was also dedicated to teaching and education. She and her husband at one point gave free lessons in scientific management. In 1940, she became the country’s first female engineering professor at Purdue. She taught at several other colleges over the years as well, including the University of Wisconsin, Bryn Mawr College, Rutgers University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She also traveled extensively delivering lectures at business conferences and colleges.

Over the years, Gilbreth lent her time to volunteering and advised several government agencies and nonprofit groups, including the Girl Scouts. During the Depression she headed the Share the Work program and the President’s Emergency Committee for Unemployment. During World War II she advised the Office of War Information and the US Navy on labor issues. She also provided similar aid during the Korean War, serving on the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services.

Gilbreth died on January 2, 1972. She received a number of awards and honors during her lifetime, and was often the first woman to receive them. Several engineering awards have been named in her honor. Additionally, two of her children wrote books about their family’s life – Cheaper by the Dozen (1948) and Belles on Their Toes (1950) – which were later turned into movies.

U.S. #1868

1984 40¢ Lillian M. Gilbreth

Great Americans

- 15th stamp in the Great Americans Series

- Honors “America’s first lady of engineering”

Stamp Category: Definitive

Series: Great Americans

Value: 40¢; ½-ounce international airmail rate

First Day of Issue: February 24, 1984

First Day City: Montclair, New Jersey

Quantity Issued: 150,000,000

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving & Printing

Printing Method: Engraved

Format: Panes of 100

Perforations: 11

Color: Dark green

Why the stamp was issued: This stamp paid the half ounce rate on international airmail.

About the stamp design: Ward Brackett created the portrait on this stamp, based on several photos of Dr. Gilbreth. Interestingly, the USPS first received a suggestion and design for a stamp featuring Dr. Gilbreth in 1982. That year, the National Society for Professional Engineers held a stamp design contest to commemorate their organization’s 50th anniversary. Their winning design depicting Gilbreth was submitted to the USPS, but wasn’t used.

First Day City: The First Day ceremony for this stamp was held at the Student Center of Montclair State College in Montclair, New Jersey, where Gilbreth’s lab was located.

About the Great Americans Series: The Great Americans Series was created to replace the Americana Series. The new series would be characterized by a standard definitive size, simple design, and monochromatic colors.

This simple design included a portrait, “USA,” the denomination, the person’s name, and in some cases, their occupation or reason for recognition. The first stamp in the new series was issued on December 27, 1980. It honored Sequoyah and fulfilled the new international postcard rate that would go into effect in January 1981.

The Great Americans Series would honor a wider range of people than the previous Prominent Americans and Liberty Series. While those series mainly honored presidents and politicians, the Great Americans Series featured people from many fields and ethnicities. They were individuals who were leaders in education, the military, literature, the arts, and human and civil rights. Plus, while the previous series only honored a few women, the Great Americans featured 15 women. This was also the first definitive series to honor Native Americans, with five stamps.

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) produced most of the stamps, but private firms printed some. Several stamps saw multiple printings. The result was many different varieties, with tagging being the key to understanding them. Though there were also differences in perforations, gum, paper, and ink color.

The final stamp in the series was issued on July 17, 1999, honoring Justin S. Morrill. Spanning 20 years, the Great Americans was the longest-running US definitive series. It was also the largest series of face-different stamps, with a total of 63.

Click here for all the individual stamps and click here for the complete series.

History the stamp represents: Lillian Evelyn Moller Gilbreth was born on May 24, 1878, in Oakland, California. Dubbed “America’s first lady of engineering,” Gilbreth combined psychology, engineering, and scientific management to improve efficiency and productivity for a number of businesses and industries.

Gilbreth was a bright child, advancing through school grade levels quickly. She was also elected vice president of her senior class in high school. Though Gilbreth’s father objected to her going to college, he agreed to let her try it for a year. Gilbreth finished that year in the top of her class and was permitted to continue her education.

At the University of California, Gilbreth majored in English while also studying philosophy and psychology. She also won a poetry contest and performed in school plays. Graduating in 1900, she was the first woman in the school’s history to give a commencement address. Gilbreth went on to earn a Masters and PhD.

Gilbreth spent her more than 40-year career combining psychology with scientific management and engineering and was a pioneer in the field of industrial and organizational psychology. In this role, she helped engineers to acknowledge the psychological aspects of their work. She introduced the idea of using psychology to study management in 1911 and was the first American engineer to combine psychology and scientific management.

Gilbreth worked with her husband Frank to run Gilbreth, Incorporated, a management consulting and industrial engineering firm. The Gilbreths also wrote several books and over 50 scientific papers together. Among the Gilbreth’s projects were time-and-motion studies. They set up video cameras to record workers and then analyzed those videos to redesign machinery that was more in-tune with workers’ movements.

These changes would also help to increase efficiency and decrease fatigue. The Gilbreths work was a precursor to the field of ergonomics. Other innovations the Gilbreths encouraged were better lighting, regular breaks, suggestion boxes, and free books. They called their program the Gilbreth System with the slogan “The One Best Way to Do Work.” Some of their clients included Macy’s and Johnson & Johnson.

After her husband’s death in 1924, Gilbreth continued to research, write, teach, and consult businesses. She also began exploring how she could apply her research to the home. She “sought to provide women with shorter, simpler, and easier ways of doing housework to enable them to seek paid employment outside the home.” As a result, Gilbreth developed the “work triangle” kitchen layout that is often still used today. She also invented the foot-pedal trash can and wall light switches, and suggested adding shelves to the inside of refrigerator doors, as well as the inclusion of the butter and egg holders. Gilbreth also filed patents for an improvement on the electric can opener and wastewater hose for washing machines.

Throughout her career, Gilbreth was also dedicated to teaching and education. She and her husband at one point gave free lessons in scientific management. In 1940, she became the country’s first female engineering professor at Purdue. She taught at several other colleges over the years as well, including the University of Wisconsin, Bryn Mawr College, Rutgers University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She also traveled extensively delivering lectures at business conferences and colleges.

Over the years, Gilbreth lent her time to volunteering and advised several government agencies and nonprofit groups, including the Girl Scouts. During the Depression she headed the Share the Work program and the President’s Emergency Committee for Unemployment. During World War II she advised the Office of War Information and the US Navy on labor issues. She also provided similar aid during the Korean War, serving on the Defense Advisory Committee on Women in the Services.

Gilbreth died on January 2, 1972. She received a number of awards and honors during her lifetime, and was often the first woman to receive them. Several engineering awards have been named in her honor. Additionally, two of her children wrote books about their family’s life – Cheaper by the Dozen (1948) and Belles on Their Toes (1950) – which were later turned into movies.