Birth Of Ernie Pyle

Pyle grew up on his family’s farm, but didn’t want to follow the family business – he wanted something more adventurous. After graduating from high school, he joined the US Navy Reserve and served three months of active duty before the end of World War I.

While attending Indiana University, Pyle discovered his knack for writing and pursued a career in journalism. The school didn’t offer a degree in journalism at the time, so he majored in economics. Despite this, he took all the journalism classes the school offered. He soon became editor of the school paper and worked on the yearbook, though he didn’t like working at a desk for long hours.

In 1922, Pyle and a few friends left school for a semester to follow the university’s baseball team to Japan. This experience gave him a great love for traveling the world. Pyle returned to school but left again a semester short of graduating to take a job as a reporter in LaPorte, Indiana. After three months there, he moved to Washington, DC to work at The Washington Daily News. Pyle remained there for a few years but quit to travel the country with his wife. Pyle served as both an editor and reporter for various newspapers. Then, in 1928, he became America’s first aviation columnist, with Amelia Earhart claiming, “Any aviator who didn’t know Pyle was a nobody.”

Pyle returned to The Washington Daily News in 1932 as managing editor. In late 1934, he took a trip to California to rest after a severe case of influenza. Asked to write a few articles about his trip, Pyle composed 11 columns with a “Mark Twain quality” that impressed his editor. He spent the next several years traveling the country and writing a national column about the unusual people and places he encountered. Titled “Hoosier Vagabond,” Pyle’s column gained him national fame and attention.

In 1940, Pyle went to London to report on the bombing by the Nazis. He then joined the enlisted men in the foxholes in Africa, writing about the reality of war and the toll it was taking on the soldiers. Soon, about 300 US papers ran Pyle’s column. Pyle quickly became regarded as “America’s most widely read correspondent.” Rather than focusing on military movements, he glorified the role of the everyday soldier – “the guys that wars can’t be won without.”

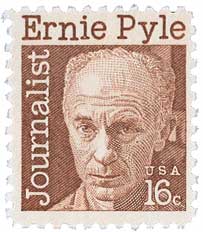

Sensitive, insightful, and humorous, Pyle brought the common man’s war to millions of Americans. He told how the nation’s young men lived, and sometimes died, as soldiers. Pyle traveled with US troops on nearly every front in Africa and Europe. After he wrote a column pushing for soldiers to get combat pay, Congress authorized “The Ernie Pyle bill,” granting ten dollars a month extra to combat infantrymen. He also won the Pulitzer Prize for journalism in 1944.

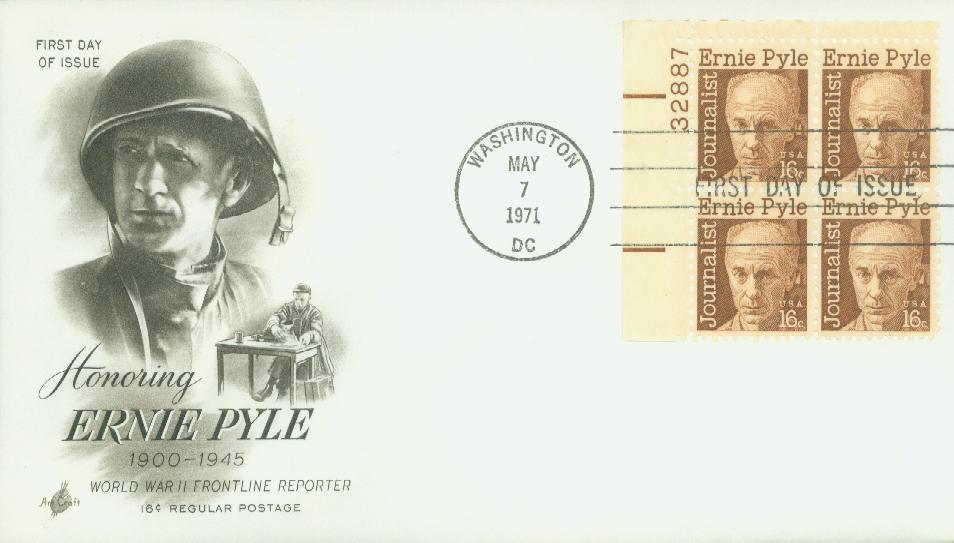

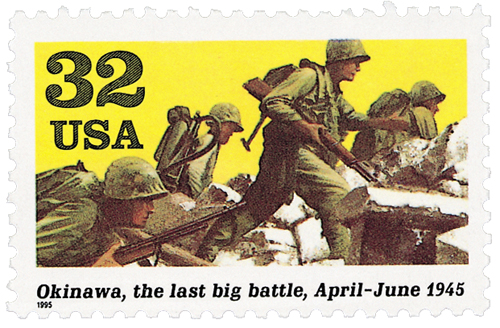

In September 1944, Pyle returned home for a vacation, but felt the pull to go back to the front. This time, Pyle traveled with the Navy to the Pacific and reported on the invasion of Okinawa. On April 18, 1945, Ernie was on Iejima Island, northwest of Okinawa. He was traveling with four other men to observe the front-line action when the jeep was fired upon by Japanese machine guns. Pyle was shot in the temple and died instantly.

Pyle was later awarded a Purple Heart, one of the few civilians to receive it. When the Navy secretary announced Pyle’s death, he said the war correspondent had “helped America understand the heroism and sacrifices of her fighting men.” President Harry Truman proclaimed, “No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen.”

Click here to discover more about Ernie Pyle.

Most Orders Ship

within 1 Business Day

90 Day Return Policy

Satisfaction Guaranteed

Earn Reward Points

for FREE Stamps & More