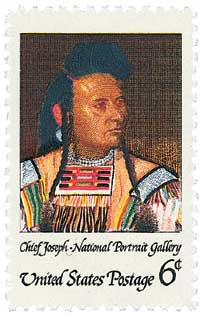

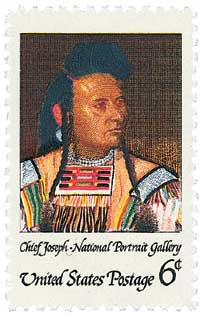

# 1364 - 1968 6c American Indian

Issue Date: November 4, 1968

Quantity: 125,100,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforations: 11

Color: Black and multicolored

Issued to honor the American Indian, this stamp pictures Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce tribe. Chief Joseph was famous for his war strategy, as well as his courage, honor, and the consideration he showed his enemies.

Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

Chief Joseph was born around 1840, the son of a chief. Joseph’s father was a Christian, and Joseph attended a mission school. In 1871, his father died, and he, in turn, became chief.

“It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” With those famous words, Chief Joseph, whose Indian name means “Thunder-traveling-to-loftier-heights,” ended the Nez Perce War.

Chief Joseph had led his people on a 15-week, more than 1,000-mile fighting retreat that ended only 40 miles from the safety of the Canadian border, where he had hoped to join Sioux Indians who had fled the United States.

Outnumbered 10-to-1, the Nez Perce repeatedly outmaneuvered the U.S. Army and actually gained the upper hand in several clashes. By the time Chief Joseph had surrendered on October 5, 1877, he was famous throughout America as “the Red Napoleon.” General William Sherman, who was very unsympathetic to the Nez Perce, praised their tactics, stating they “fought with almost scientific skill, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines, and field fortifications.”

The fighting began in 1877, when the U.S. government ordered the Nez Perce to move to an undesirable reservation far from their traditional home in Oregon’s Wallowa Valley. After the surrender, the Nez Perce were promised they could again return to their tribal land. And although some eventually did, Chief Joseph never again saw the land of his birth.

Before his death in 1904, Chief Joseph personally spoke to President William McKinley on behalf of his people.

Bureau Of Indian Affairs

Among the first acts of the new Continental Congress in 1775 was the creation of three departments of Indian affairs: northern, central, and southern. Benjamin Franklin and Patrick Henry served as some of the early commissioners of these departments, tasked with negotiating treaties with Native American tribes. Their goal was to establish tribal neutrality in the Revolutionary War.

In 1789, the US Congress created the War Department and included Native American relations as part of its duties. Then in 1806, the Office of Indian Trade was established to oversee the fur-trading network, which included some control in Native American territories.

When this system ended in 1822, there was a gap in Native American relations. US Secretary of War John C. Calhoun sought to bridge that gap by creating the Bureau of Indian Affairs on March 11, 1824. It was a division within his Department of War and he created it without authorization from Congress. Because he had created the office in this way, Calhoun retained authority over the office, while the bureau’s superintendent had little power. It would take five years before a bill passed in both houses giving the president the authority to appoint a Commissioner of Indian Affairs to officially direct and manage all government matters relating to Native Americans.

In 1849, the office was transferred to the US Department of the Interior, which brought about several changes in policy and responsibilities. Over the years, tribes that had been moved to reservations suffered from diseases and starvation, leading the bureau to start providing food and supplies. However, by the 1860s, a series of corrupt bureau agents failed to do their jobs properly, leading to widespread hostility on the reservations.

So in 1867, Congress created a Peace Commission to examine the issues and suggest changes. Among their many suggestions was the appointment of more honest agents. While this change was made, their suggestion of removing the bureau from the Interior Department never happened. In the coming years, the bureau had a larger influence on reservations – running schools, participating in law enforcement, handing out supplies, and leasing contracts.

The bureau continued on this path until 1938 when the Merriam Report revealed that they weren’t properly providing services to reservations. Congress then passed the Indian Reorganization Act to help boost the tribal economies and governments. The bureau also expanded its services to include forestry, range management, and construction. The bureau’s services continued to expand until the 1960s, when some of these duties, such as education and healthcare, were passed to other departments.

Since the 1970s, the bureau has followed a policy of self-determination, promoting tribal resources and rights and their ability to manage their own governments. The current mission of the bureau is to “enhance the quality of life, to promote economic opportunity, and to carry out the responsibility to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian tribes, and Alaska Natives.”

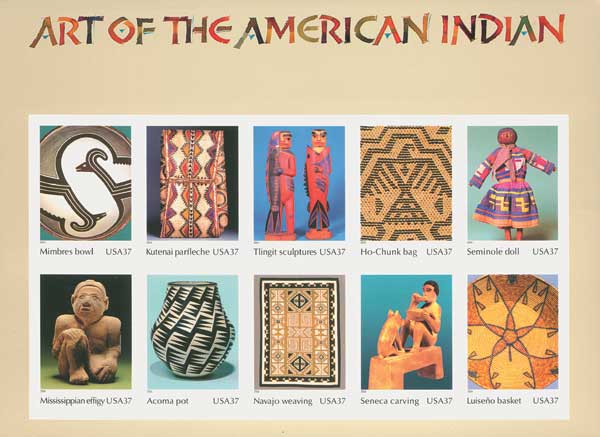

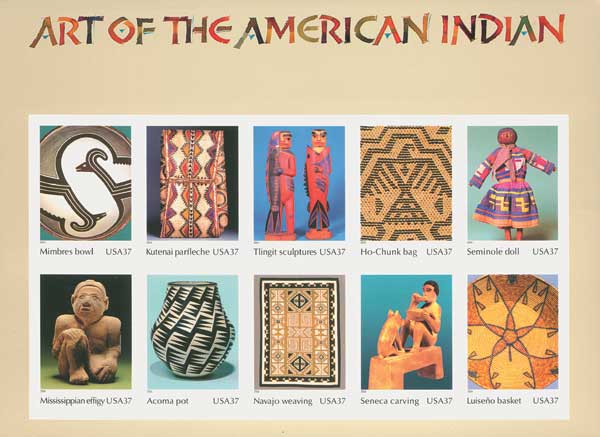

Click here for more stamps honoring Native Americans.

Click here to view the bureau’s website.

Issue Date: November 4, 1968

Quantity: 125,100,000

Printed By: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Lithographed, engraved

Perforations: 11

Color: Black and multicolored

Issued to honor the American Indian, this stamp pictures Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce tribe. Chief Joseph was famous for his war strategy, as well as his courage, honor, and the consideration he showed his enemies.

Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

Chief Joseph was born around 1840, the son of a chief. Joseph’s father was a Christian, and Joseph attended a mission school. In 1871, his father died, and he, in turn, became chief.

“It is cold, and we have no blankets. The little children are freezing to death. My heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” With those famous words, Chief Joseph, whose Indian name means “Thunder-traveling-to-loftier-heights,” ended the Nez Perce War.

Chief Joseph had led his people on a 15-week, more than 1,000-mile fighting retreat that ended only 40 miles from the safety of the Canadian border, where he had hoped to join Sioux Indians who had fled the United States.

Outnumbered 10-to-1, the Nez Perce repeatedly outmaneuvered the U.S. Army and actually gained the upper hand in several clashes. By the time Chief Joseph had surrendered on October 5, 1877, he was famous throughout America as “the Red Napoleon.” General William Sherman, who was very unsympathetic to the Nez Perce, praised their tactics, stating they “fought with almost scientific skill, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines, and field fortifications.”

The fighting began in 1877, when the U.S. government ordered the Nez Perce to move to an undesirable reservation far from their traditional home in Oregon’s Wallowa Valley. After the surrender, the Nez Perce were promised they could again return to their tribal land. And although some eventually did, Chief Joseph never again saw the land of his birth.

Before his death in 1904, Chief Joseph personally spoke to President William McKinley on behalf of his people.

Bureau Of Indian Affairs

Among the first acts of the new Continental Congress in 1775 was the creation of three departments of Indian affairs: northern, central, and southern. Benjamin Franklin and Patrick Henry served as some of the early commissioners of these departments, tasked with negotiating treaties with Native American tribes. Their goal was to establish tribal neutrality in the Revolutionary War.

In 1789, the US Congress created the War Department and included Native American relations as part of its duties. Then in 1806, the Office of Indian Trade was established to oversee the fur-trading network, which included some control in Native American territories.

When this system ended in 1822, there was a gap in Native American relations. US Secretary of War John C. Calhoun sought to bridge that gap by creating the Bureau of Indian Affairs on March 11, 1824. It was a division within his Department of War and he created it without authorization from Congress. Because he had created the office in this way, Calhoun retained authority over the office, while the bureau’s superintendent had little power. It would take five years before a bill passed in both houses giving the president the authority to appoint a Commissioner of Indian Affairs to officially direct and manage all government matters relating to Native Americans.

In 1849, the office was transferred to the US Department of the Interior, which brought about several changes in policy and responsibilities. Over the years, tribes that had been moved to reservations suffered from diseases and starvation, leading the bureau to start providing food and supplies. However, by the 1860s, a series of corrupt bureau agents failed to do their jobs properly, leading to widespread hostility on the reservations.

So in 1867, Congress created a Peace Commission to examine the issues and suggest changes. Among their many suggestions was the appointment of more honest agents. While this change was made, their suggestion of removing the bureau from the Interior Department never happened. In the coming years, the bureau had a larger influence on reservations – running schools, participating in law enforcement, handing out supplies, and leasing contracts.

The bureau continued on this path until 1938 when the Merriam Report revealed that they weren’t properly providing services to reservations. Congress then passed the Indian Reorganization Act to help boost the tribal economies and governments. The bureau also expanded its services to include forestry, range management, and construction. The bureau’s services continued to expand until the 1960s, when some of these duties, such as education and healthcare, were passed to other departments.

Since the 1970s, the bureau has followed a policy of self-determination, promoting tribal resources and rights and their ability to manage their own governments. The current mission of the bureau is to “enhance the quality of life, to promote economic opportunity, and to carry out the responsibility to protect and improve the trust assets of American Indians, Indian tribes, and Alaska Natives.”

Click here for more stamps honoring Native Americans.

Click here to view the bureau’s website.