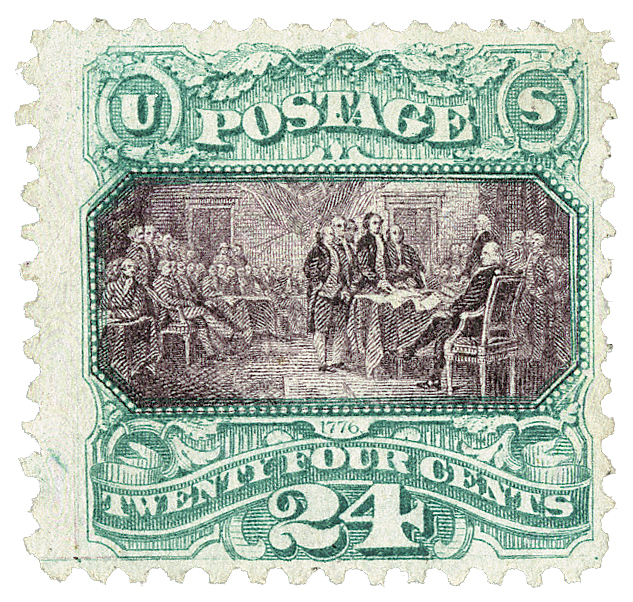

U.S. #130

1875 15¢ Declaration of Independence

1875 Re-Issue of 1869 Issue

Earliest Known Use: March 27, 1880

Quantity sold: 2,091

Printed by: National Bank Note Company

Method: Flat plate

Watermark: None

Perforation: 12

Color: Green and Violet

As the nation’s centennial approached, organizers began planning a grand celebration in Philadelphia. It would be the first World’s Fair to be held in the United States. To commemorate the event, the Post Office Department reproduced all US postal issues for display and sale at the Centennial Exhibition.

Originally produced with a “G” grill, the 1869 Pictorial designs were reissued in 1875 without grills. The reissues were not sold at regular stamp windows, but were made for a Post Office Department display at the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Sets were sold directly to collectors by the Post Office Department in Washington, DC.

The National Bank Note Company produced the reprints in 1875. They are on hard white paper, and feature crackly white gum. A new plate of 150 subjects was made for the 1¢ and for the frame of the 15¢. The frame on the 15¢ is the same as type I but without the fringe of brown shading lines around the central vignette.

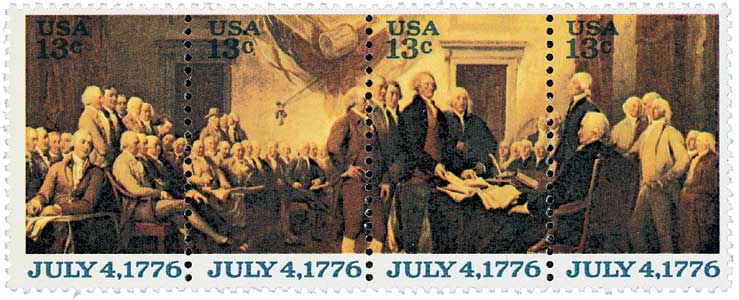

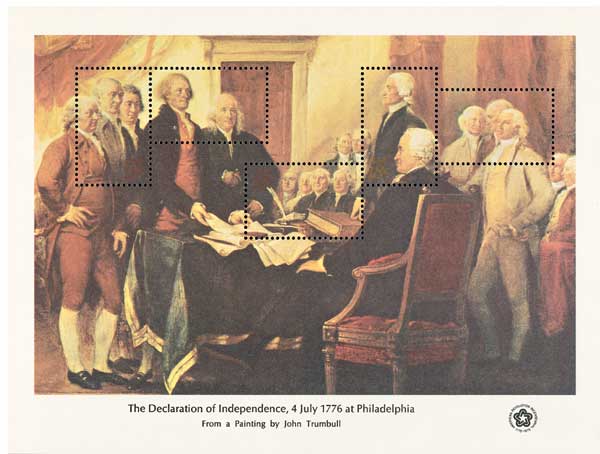

America’s Declaration of Independence

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence. One of America’s founding documents, it explained why the 13 colonies were at war with Great Britain and that they declared themselves to be independent sovereign states no longer under British rule. In the spring of 1776, the Second Continental Congress appointed a “Committee of Five” to draft a document officially proclaiming independence from Great Britain. The committee consisted of John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston, Roger Sherman, and Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, not knowing anyone in the Congress, soon became close friends with Adams, a friendship that would last the rest of their lives. After creating a basic outline for the document, the men discussed who should write it. They all agreed, especially Jefferson, that Adams should write it. However, Adams convinced them to choose Jefferson, an assignment he was not thrilled about at the beginning. Over the next 17 days, Jefferson had little time to draft the declaration, but when he worked on it, it was reportedly on a special desk of his own creation. Jefferson had several influences that included his own draft of the preamble of the Constitution of Virginia, George Mason’s draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights , the English Declaration of Rights (which officially ended the reign of King James II), the Scottish Declaration of Arbroath, and the Dutch Act of Abjuration. Several other sources have been suggested over time by historians, but many are disputed. Jefferson recognized that he used several sources, stating in 1825, “Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.” Once completed, Jefferson presented the document to the committee, which made several changes, including Benjamin Franklin’s suggestion to replace the statement “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” with “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” On June 28, 1776, the committee presented the Congress with “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress Assembled.” The Congress then voted on the resolution of independence on July 2, a day Adams first anticipated America would celebrate. Congress then reviewed the declaration and cut nearly one-quarter of the text, including a passage criticizing the slave trade, which Jefferson resented. In the document, the equal value of all people was stated, and the rights of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” were called “unalienable,” because they could not be taken away. The bold writers called King George III “unfit to be the ruler of a free people” and accused him of obstructing “the Administration of Justice.” The wording was officially approved, and the document ratified on July 4. The declaration was then distributed and read publicly. Contrary to popular belief, the famous “official” document that’s on display at the national archives, wasn’t signed until August 2.