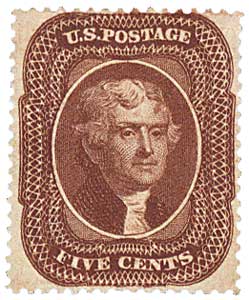

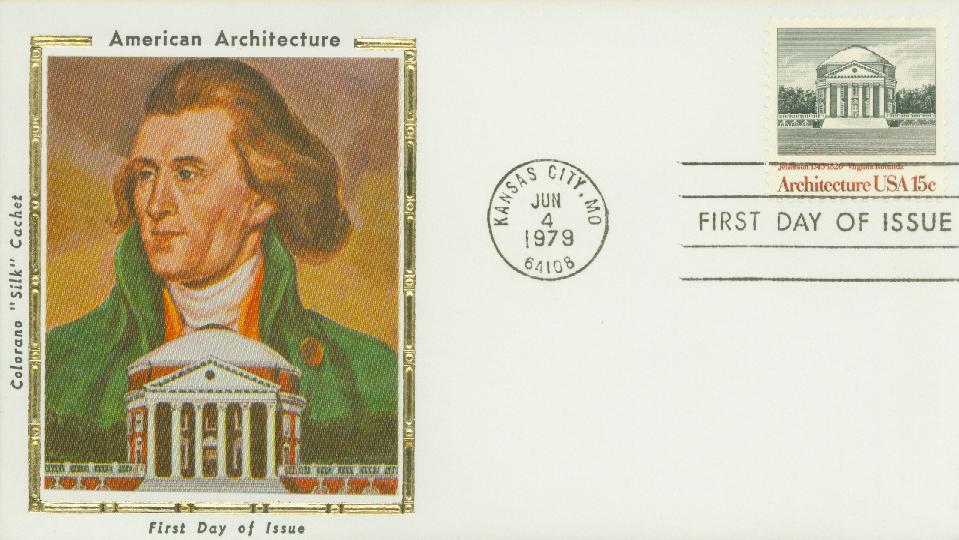

# 1278 - 1968 1c Prominent Americans: Thomas Jefferson

1¢ Thomas Jefferson

Prominent Americans Series

City: Jeffersonville, IN

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Color: Green

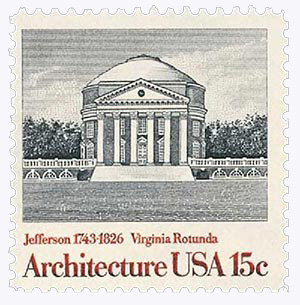

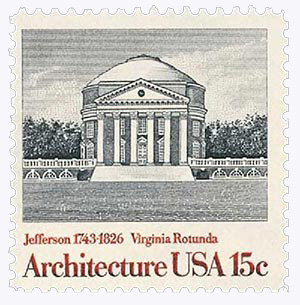

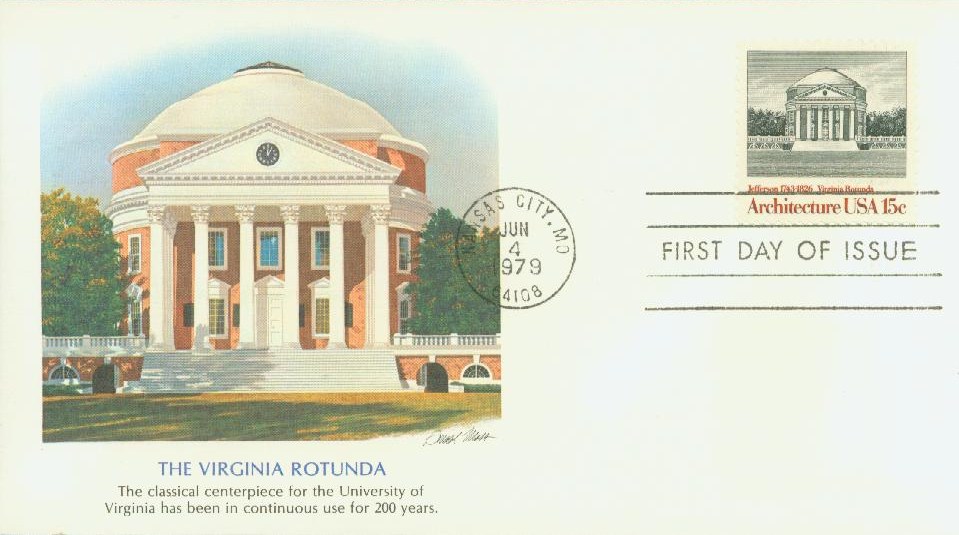

Jefferson’s University Of Virginia

On January 25, 1819, Thomas Jefferson succeeded in securing a charter for his beloved University of Virginia (UVA).

Jefferson had long wanted to establish a school in Virginia. He had attended The College of William and Mary but grew unhappy with its religious stances and lack of science courses.

In 1800, while still serving as Vice President, he wrote to scientist Joseph Priestley, “We wish to establish in the upper country of Virginia, and more centrally for the State, a University on a plan so broad and liberal and modern, as to be worth patronizing with the public support, and be a temptation to the youth of other States to come and drink of the cup of knowledge and fraternize with us.” And as president, Jefferson continued to muse over the idea of the university, writing it would be “on the most extensive and liberal scale that our circumstances would call for and our faculties meet.”

Jefferson resolved to establish his own school in Virginia and spent several years planning and gaining support. In 1817, he and fellow presidents James Monroe and James Madison met with John Marshall and 24 other dignitaries to select a site for the school. They chose Charlottesville, where James Monroe had purchased a plot of land years before. The Board of Visitors purchased the land and laid the first cornerstone later that same year. At the time, they called the school Central College.

Then on January 25, 1819, the Virginia General Assembly voted to grant the school a charter as the University of Virginia. Over the next several years, Jefferson was involved in all aspects of the school’s creation, from drawing the plans for its buildings to hiring faculty. The building was one of the largest construction projects in the history of North America at the time. On March 7, 1825, Jefferson had the pleasure of seeing the university open its doors to its first class of students.

At the time of its opening, UVA was quite different from the other schools of the day. At the time, most schools offered study in a single course, such as medicine, law, or divinity. But at UVA, students could study in up to eight different independent schools – medicine, law, mathematics, chemistry, ancient languages, modern languages, natural philosophy, and moral philosophy. Another major difference was that the school wasn’t centered on religion. In fact, while most schools had a chapel at their heart, UVA had a library.

After the school opened, Jefferson remained intensely involved. He hosted Sunday dinners at his Monticello home for both students and teachers. Jefferson saw UVA as one of his greatest accomplishments and it was one of his most beloved achievements. So much so, that he insisted it be included on his gravestone.

During the Civil War, UVA was one of the few colleges in the South to remain open during the fighting. At one point, Union troops captured Charlottesville, but the school’s faculty convinced George Armstrong Custer to spare the school because it was such a large part of Jefferson’s legacy. He agreed and they left days later, and classes were able to continue.

In 1875, a grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia made it so that all Virginians could attend the school for free. The school was unique in that it had no president, as directed by Jefferson. However, that changed in 1904 when Edwin Alderman became the school’s first president. He was a significant fund-raiser and helped reform and modernize the school. He also created new departments in geology, forestry, education, and commerce.

Over the years, several notable Americans have attended UVA, including President Woodrow Wilson, explorer Richard Byrd, poet Edgar Allan Poe, Senators Robert, and Teddy Kennedy, and US Secretary of the Treasury John Snow.

Click here for more Jefferson stamps.

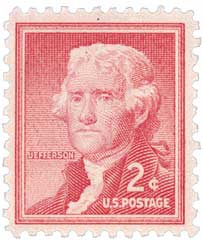

1¢ Thomas Jefferson

Prominent Americans Series

City: Jeffersonville, IN

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Color: Green

Jefferson’s University Of Virginia

On January 25, 1819, Thomas Jefferson succeeded in securing a charter for his beloved University of Virginia (UVA).

Jefferson had long wanted to establish a school in Virginia. He had attended The College of William and Mary but grew unhappy with its religious stances and lack of science courses.

In 1800, while still serving as Vice President, he wrote to scientist Joseph Priestley, “We wish to establish in the upper country of Virginia, and more centrally for the State, a University on a plan so broad and liberal and modern, as to be worth patronizing with the public support, and be a temptation to the youth of other States to come and drink of the cup of knowledge and fraternize with us.” And as president, Jefferson continued to muse over the idea of the university, writing it would be “on the most extensive and liberal scale that our circumstances would call for and our faculties meet.”

Jefferson resolved to establish his own school in Virginia and spent several years planning and gaining support. In 1817, he and fellow presidents James Monroe and James Madison met with John Marshall and 24 other dignitaries to select a site for the school. They chose Charlottesville, where James Monroe had purchased a plot of land years before. The Board of Visitors purchased the land and laid the first cornerstone later that same year. At the time, they called the school Central College.

Then on January 25, 1819, the Virginia General Assembly voted to grant the school a charter as the University of Virginia. Over the next several years, Jefferson was involved in all aspects of the school’s creation, from drawing the plans for its buildings to hiring faculty. The building was one of the largest construction projects in the history of North America at the time. On March 7, 1825, Jefferson had the pleasure of seeing the university open its doors to its first class of students.

At the time of its opening, UVA was quite different from the other schools of the day. At the time, most schools offered study in a single course, such as medicine, law, or divinity. But at UVA, students could study in up to eight different independent schools – medicine, law, mathematics, chemistry, ancient languages, modern languages, natural philosophy, and moral philosophy. Another major difference was that the school wasn’t centered on religion. In fact, while most schools had a chapel at their heart, UVA had a library.

After the school opened, Jefferson remained intensely involved. He hosted Sunday dinners at his Monticello home for both students and teachers. Jefferson saw UVA as one of his greatest accomplishments and it was one of his most beloved achievements. So much so, that he insisted it be included on his gravestone.

During the Civil War, UVA was one of the few colleges in the South to remain open during the fighting. At one point, Union troops captured Charlottesville, but the school’s faculty convinced George Armstrong Custer to spare the school because it was such a large part of Jefferson’s legacy. He agreed and they left days later, and classes were able to continue.

In 1875, a grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia made it so that all Virginians could attend the school for free. The school was unique in that it had no president, as directed by Jefferson. However, that changed in 1904 when Edwin Alderman became the school’s first president. He was a significant fund-raiser and helped reform and modernize the school. He also created new departments in geology, forestry, education, and commerce.

Over the years, several notable Americans have attended UVA, including President Woodrow Wilson, explorer Richard Byrd, poet Edgar Allan Poe, Senators Robert, and Teddy Kennedy, and US Secretary of the Treasury John Snow.

Click here for more Jefferson stamps.