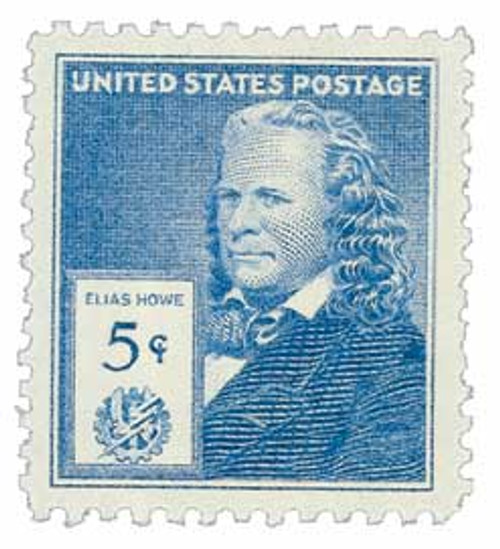

# 892 - 1940 Famous Americans: 5c Elias Howe

1940 5¢ Elias Howe

Famous Americans Series – Inventors

First City: Spencer, Massachusetts

Quantity Issued: 20,264,580

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 10 ½ x 11

Color: Ultramarine

Elias Howe Patents First Lockstitch Sewing Machine

After eight years of tinkering, Elias Howe was awarded the first U.S. patent for a practical lockstitch sewing machine on September 10, 1846.

Howe didn’t invent the first sewing machine – various forms of mechanized sewing had been used as early as 1790. Over the years, various inventors created and even patented sewing machines, but none produced a durable enough stitch to replace hand-sewing. Walter Hunt came close in the early 1830s. He invented a back-stitch sewing machine, but refused to patent it for fear of the jobs it would take away from seamstresses.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, Elias Howe was working for machinist Ari Davis. Davis once told Howe that whoever invented a practical sewing machine would be rich. And so, Howe set about being that man. He worked on the machine for eight years in his spare time, working out the logistics.

Howe’s machine differed from his contemporaries (and laid the groundwork for modern machines) in that he placed the eye near the point of the needle, included a shuttle beneath the cloth to create a durable lock stitch, and had an automatic feed to move the cloth through. When he demonstrated his machine in 1845, it could make 250 stitches per minute, out-sewing five seamstresses. However, at $300 (over $9,600 today) it was a tough sell. Howe patented his design the following year, but was a poor businessman and had a string of bad luck – his workshop burned down and he was swindled out of British royalties.

Sewing machines quickly grew in popularity, and it appeared that other people were using features of his patent on their machines. In 1854, Howe sued for patent infringement and eventually won. Two years later, he joined other manufacturers to create the first American patent pool, allowing them to all share the wealth of their creations and avoid going to court. With this new arrangement, Howe received $5 royalty for every sewing machine sold in the U.S., amounting to $2 million. He finally achieved his goal.

1940 5¢ Elias Howe

Famous Americans Series – Inventors

First City: Spencer, Massachusetts

Quantity Issued: 20,264,580

Printed by: Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 10 ½ x 11

Color: Ultramarine

Elias Howe Patents First Lockstitch Sewing Machine

After eight years of tinkering, Elias Howe was awarded the first U.S. patent for a practical lockstitch sewing machine on September 10, 1846.

Howe didn’t invent the first sewing machine – various forms of mechanized sewing had been used as early as 1790. Over the years, various inventors created and even patented sewing machines, but none produced a durable enough stitch to replace hand-sewing. Walter Hunt came close in the early 1830s. He invented a back-stitch sewing machine, but refused to patent it for fear of the jobs it would take away from seamstresses.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, Elias Howe was working for machinist Ari Davis. Davis once told Howe that whoever invented a practical sewing machine would be rich. And so, Howe set about being that man. He worked on the machine for eight years in his spare time, working out the logistics.

Howe’s machine differed from his contemporaries (and laid the groundwork for modern machines) in that he placed the eye near the point of the needle, included a shuttle beneath the cloth to create a durable lock stitch, and had an automatic feed to move the cloth through. When he demonstrated his machine in 1845, it could make 250 stitches per minute, out-sewing five seamstresses. However, at $300 (over $9,600 today) it was a tough sell. Howe patented his design the following year, but was a poor businessman and had a string of bad luck – his workshop burned down and he was swindled out of British royalties.

Sewing machines quickly grew in popularity, and it appeared that other people were using features of his patent on their machines. In 1854, Howe sued for patent infringement and eventually won. Two years later, he joined other manufacturers to create the first American patent pool, allowing them to all share the wealth of their creations and avoid going to court. With this new arrangement, Howe received $5 royalty for every sewing machine sold in the U.S., amounting to $2 million. He finally achieved his goal.