1938 7c Jackson, brown

# 812 - 1938 7c Jackson, brown

$0.35 - $95.00

U.S. #812

1938 7¢ Andrew Jackson

Presidential Series

1938 7¢ Andrew Jackson

Presidential Series

Issue Date: August 4, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 3,906,545,800

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Sepia

Known affectionately as the “Prexies,” the 1938 Presidential series is a favorite among stamp collectors.

The series was issued in response to public clamoring for a new Regular Issue series. The series that was current at the time had been in use for more than a decade. President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed, and a contest was staged. The public was asked to submit original designs for a new series picturing all deceased U.S. Presidents. Over 1,100 sketches were submitted, many from veteran stamp collectors. Elaine Rawlinson, who had little knowledge of stamps, won the contest and collected the $500 prize. Rawlinson was the first stamp designer since the Bureau of Engraving and Printing began producing U.S. stamps who was not a government employee.

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the last Revolutionary War veteran and the second prisoner of war to serve as President. He was a successful frontier lawyer who gained national fame for his heroic victories during the War of 1812. Jackson was a tough military leader, earning the nickname “Old Hickory.” Despite losing the election of 1824, he successfully won the elections of 1828 and 1832. As President, he fought for the rights of the common man and worked to ensure his country remained a unified nation. He introduced the spoils system (rewarding supporters with public offices), effectively closed the Second Bank of the United States, and helped shape the modern Democratic party. After leaving office, he remained an active voice in politics, especially in Martin Van Buren’s presidential campaign, until Jackson’s death in 1845.

Jackson’s Early Life

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, in the Waxhaws area near the border between North and South Carolina. His parents were Scots-Irish immigrants Andrew (who had died three weeks before his son was born) and Elizabeth Jackson. Andrew was the youngest of three sons.

Andrew received a minimal education in a small “old field school.” In 1779, his brother Hugh was killed at the Battle of Stono Ferry. Two years later, when Andrew was 13, he joined the American Revolution as a courier along with his brother Robert. The brothers were captured by British troops and nearly starved to death while being held as prisoners of war. They contracted smallpox and were eventually released by their mother’s bargaining. Shortly after their return home, Robert died from injuries and illness sustained while in British captivity. That same year, Jackson’s mother traveled to Charleston to nurse American prisoners of war, and died of ship fever or cholera. Orphaned at age 14, Andrew bitterly resented the British for the rest of his life.

Early Political Career

After working briefly as a saddle maker and teacher, Andrew studied law in North Carolina. Admitted to the bar in 1787, he became a successful frontier lawyer. Jackson quickly proved himself as a tough and effective lawyer, often arguing cases over land claims, assaults, and battery.

By 1788, Andrew Jackson was appointed Solicitor of the Western District and lived as a boarder in Rachel Stockley Donelson’s house in Nashville. Here he met her daughter, Rachel Donelson Robards, who was unhappily married to Captain Lewis Robards. After receiving what they thought were final divorce papers from Captain Robards, Andrew and Rachel were married three years later. After two years of marriage, they discovered the divorce was never finalized. Once it was, Andrew and Rachel were remarried in 1794.

Two years later, Jackson was a delegate to the Tennessee constitutional convention and was elected U.S. representative upon statehood. In 1797 he joined the U.S. Senate as a Democratic-Republican, serving for one year until he was appointed Tennessee Supreme Court Judge.

Military Career

In 1801, Jackson resumed his military career when he was appointed colonel of the Tennessee militia. An attack on white settlements by Tecumseh and the “Red Stick” Creek Indians during the War of 1812 prompted Jackson to take command. Leading the Tennessee militia, U.S. troops, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Southern Creek Indians, Jackson defeated the Red Stick Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. He then enacted the Treaty of Fort Jackson, taking 20 million acres from the Northern Creek enemies and Southern Creek allies for white settlers. Jackson’s commanding leadership earned him an appointment as major general.

Jackson’s success in the War of 1812 continued in New Orleans. On January 8, 1815, Jackson’s militia of 5,000 soldiers overpowered the British army of more than 7,500 troops. Jackson’s men inflicted over 2,000 casualties, while only losing 13 of their own. A strict but popular leader, Jackson earned the nickname “Old Hickory” for his toughness on the battlefield. His heroics in this incident earned him the recognition of Congress and a gold medal.

The famous General returned to serve his country once again in December 1817 during the First Seminole War. Jackson was sent to Georgia to face the Seminole and Creek Indians, as well as prevent runaway slaves from escaping to Spanish Florida. Following a Seminole attack on his Tennessee volunteers, Jackson retaliated by burning their unguarded villages and crops. Jackson found numerous letters proving that the Spanish and British were secretly helping the Indians.

Jackson took control of Pensacola, removed the Spanish governor, and tried and executed two British subjects who had been helping the Indians. Stories of Jackson’s ruthlessness spread through the Seminole tribes and created an international incident. While some found fault with Jackson’s actions, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams supported him and urged Spain to protect or cede the area to the U.S. As a result of Jackson’s actions and Adams’ ultimatum, the U.S. acquired the Florida Territory through the Adams-Onis Treaty. Jackson was rewarded for his heroics and appointed military governor.

Election of 1824

In 1822, the Tennessee Legislature nominated Jackson for President and elected him U.S. Senator. Two years later, the Democratic-Republican Party was the only national political party. The election of 1824 put Jackson against Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and House Speaker Henry Clay. Although Jackson had the most popular votes, he did not have a majority, so the decision was left to the House of Representatives. Adams was elected President, which Jackson believed was part of a “corrupt bargain” that resulted in Clay’s appointment to Secretary of State.

Election of 1828

The following year, Jackson left the Senate to make a second presidential bid. Again nominated by the Tennessee legislature, Jackson gained the support of John C. Calhoun, Martin Van Buren, and Thomas Ritchie. Van Buren brought back the old Republican Party, renaming it the Democratic Party, with Jackson as their leader. Jackson’s rivals began calling him “jackass,” a name he liked. Although he only used it temporarily, the symbol was later revived when cartoonist Thomas Nast used it for the Democratic Party, and remains its symbol to this day.

Jackson won the election over Adams, but time to enjoy his victory was cut short when his wife Rachel died suddenly on December 22, 1828. Throughout the campaign, Jackson’s rivals had attacked him and his wife for their alleged adultery following their first illegitimate marriage. These accusations took their toll on Rachel, and Jackson believed the stress caused her early death.

Presidency

Jackson’s inauguration was the first presidential inauguration open to the public. The White House was filled with citizens from many classes, standing on chairs to get a glimpse of the man of the people. At one point, many fine White House plates and other items were damaged, and the people were coaxed outside with barrels of drinks.

Without his wife to act as First Lady, Jackson enlisted Rachel’s niece, Emily Donelson, to serve as White House Hostess. In 1834, Emily shared the duties with Sarah Yorke Jackson (wife of Andrew Jackson, Jr.) until Emily’s death in 1836, when Sarah took over all responsibilities. This was the only time in history when two women served as White House hostesses at the same time.

With Jackson’s election as President, a new era in political philosophy was introduced: the Jacksonian Democracy. Jackson aimed to introduce equality for the common man, which he achieved in part by expanding voting rights to include all white male adults, rather than just land owners. This in part helped him achieve his goal of increasing public participation in government. Jackson was also a supporter of Manifest Destiny, the belief that it was America’s destiny to settle the American West, controlling North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Additionally, Jackson planted the seeds for a spoils system in which political appointees were rotated in and out of office, to keep individuals from serving for long periods and possibly corrupting their positions. In 1835, Jackson successfully lowered the federal debt to just $33,733.05, its lowest since 1791.

Another obstacle Jackson faced as President was the Second Bank of the United States. Established in 1816 to help recover from the War of 1812, the national bank was nearing the end of its charter and needed to be renewed. Jackson did not support this, because he felt that it was dangerous to invest all of the country’s money into one bank. The bank also helped the wealthy get richer and was more beneficial to people of northeastern states. Jackson felt the bank made the U.S. government vulnerable to foreign interests. As a result, Jackson successfully vetoed the bank’s request for a re-charter and had all U.S. government funds removed to other banks.

In 1836, Jackson introduced the Specie Circular, requiring people who bought government land to pay in specie (gold or silver coins). The banks did not have enough specie, creating a greater demand that could not be filled. The banks that could not provide the money closed, causing the Panic of 1837, and a depression that lasted for years.

Jackson was also faced with another crisis while in office – the Nullification Crisis or Secession Crisis of 1828-32. Some people believed that high tariffs (the Tariff of Abominations) on European imports made those same goods more expensive than those from the northern states, which raised the prices the southern planters paid. Southerners felt that these high tariffs benefitted northern industrialists while hurting southern farmers. The issue became more complicated for President Jackson when his Vice President, John C. Calhoun, part of the South Carolina Exposition and Protest of 1828, sided with his home state of South Carolina. Calhoun believed that South Carolina had the right to nullify, or declare void, the tariff. In fact, he believed any state had the right to nullify any Federal laws that went against a state’s interests. Jackson was sympathetic to the southern states’ concerns over the fairness of the tariffs, but above all, he believed in a strong Union.

The following year, Calhoun left Jackson’s cabinet and was replaced by Martin Van Buren. Calhoun returned to South Carolina to serve as Senator, and Jackson asked Congress to pass a Force Bill, allowing troops to enter South Carolina to resolve the problem. Jackson told Congress that “The Constitution... forms a government not a league...To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States is not a nation.” When Clay and the protectionists agreed to a Compromise Tariff, they retracted their Nullification Ordinance and the Force Bill was no longer necessary.

One of the most controversial issues of Jackson’s administration was his policy concerning American Indians. While Jackson said it was “unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land,” he also believed that “if they remain within the limits of the States they must be subject to their laws.” In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act, giving the President the authority to negotiate the purchase of Indian land in the east in exchange for lands west of the U.S. border.

This legislation was unpopular in the North, but Southerners supported it due to recent discoveries of gold on Cherokee land. A meeting between Cherokee John Ridge and U.S. politicians resulted in the Treaty of New Echota, which many Indians rejected because they did not see Ridge as their leader. Van Buren then sent 7,000 troops to remove the Cherokees, resulting in over 4,000 Cherokee deaths along the “Trail of Tears.” In the end, over 45,000 American Indians were moved west, with the U.S. government purchasing nearly 100 million acres of Indian land plus an additional 32 million acres of western land.

Retirement

In 1837, Andrew Jackson retired to his Nashville home, The Hermitage. Even in retirement, he was an active voice in American politics. He had a large role in both of Martin Van Buren’s presidential campaigns, the first of which Van Buren won. Jackson helped in the acquisition of Texas and was a strong supporter of future President James K. Polk. Jackson died on June 8, 1845, from tuberculosis and heart failure., D.C.

U.S. #812

1938 7¢ Andrew Jackson

Presidential Series

1938 7¢ Andrew Jackson

Presidential Series

Issue Date: August 4, 1938

First City: Washington, DC

Quantity Issued: 3,906,545,800

Printing Method: Rotary press

Perforations: 11 x 10 ½

Color: Sepia

Known affectionately as the “Prexies,” the 1938 Presidential series is a favorite among stamp collectors.

The series was issued in response to public clamoring for a new Regular Issue series. The series that was current at the time had been in use for more than a decade. President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed, and a contest was staged. The public was asked to submit original designs for a new series picturing all deceased U.S. Presidents. Over 1,100 sketches were submitted, many from veteran stamp collectors. Elaine Rawlinson, who had little knowledge of stamps, won the contest and collected the $500 prize. Rawlinson was the first stamp designer since the Bureau of Engraving and Printing began producing U.S. stamps who was not a government employee.

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson was the last Revolutionary War veteran and the second prisoner of war to serve as President. He was a successful frontier lawyer who gained national fame for his heroic victories during the War of 1812. Jackson was a tough military leader, earning the nickname “Old Hickory.” Despite losing the election of 1824, he successfully won the elections of 1828 and 1832. As President, he fought for the rights of the common man and worked to ensure his country remained a unified nation. He introduced the spoils system (rewarding supporters with public offices), effectively closed the Second Bank of the United States, and helped shape the modern Democratic party. After leaving office, he remained an active voice in politics, especially in Martin Van Buren’s presidential campaign, until Jackson’s death in 1845.

Jackson’s Early Life

Andrew Jackson was born on March 15, 1767, in the Waxhaws area near the border between North and South Carolina. His parents were Scots-Irish immigrants Andrew (who had died three weeks before his son was born) and Elizabeth Jackson. Andrew was the youngest of three sons.

Andrew received a minimal education in a small “old field school.” In 1779, his brother Hugh was killed at the Battle of Stono Ferry. Two years later, when Andrew was 13, he joined the American Revolution as a courier along with his brother Robert. The brothers were captured by British troops and nearly starved to death while being held as prisoners of war. They contracted smallpox and were eventually released by their mother’s bargaining. Shortly after their return home, Robert died from injuries and illness sustained while in British captivity. That same year, Jackson’s mother traveled to Charleston to nurse American prisoners of war, and died of ship fever or cholera. Orphaned at age 14, Andrew bitterly resented the British for the rest of his life.

Early Political Career

After working briefly as a saddle maker and teacher, Andrew studied law in North Carolina. Admitted to the bar in 1787, he became a successful frontier lawyer. Jackson quickly proved himself as a tough and effective lawyer, often arguing cases over land claims, assaults, and battery.

By 1788, Andrew Jackson was appointed Solicitor of the Western District and lived as a boarder in Rachel Stockley Donelson’s house in Nashville. Here he met her daughter, Rachel Donelson Robards, who was unhappily married to Captain Lewis Robards. After receiving what they thought were final divorce papers from Captain Robards, Andrew and Rachel were married three years later. After two years of marriage, they discovered the divorce was never finalized. Once it was, Andrew and Rachel were remarried in 1794.

Two years later, Jackson was a delegate to the Tennessee constitutional convention and was elected U.S. representative upon statehood. In 1797 he joined the U.S. Senate as a Democratic-Republican, serving for one year until he was appointed Tennessee Supreme Court Judge.

Military Career

In 1801, Jackson resumed his military career when he was appointed colonel of the Tennessee militia. An attack on white settlements by Tecumseh and the “Red Stick” Creek Indians during the War of 1812 prompted Jackson to take command. Leading the Tennessee militia, U.S. troops, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Southern Creek Indians, Jackson defeated the Red Stick Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814. He then enacted the Treaty of Fort Jackson, taking 20 million acres from the Northern Creek enemies and Southern Creek allies for white settlers. Jackson’s commanding leadership earned him an appointment as major general.

Jackson’s success in the War of 1812 continued in New Orleans. On January 8, 1815, Jackson’s militia of 5,000 soldiers overpowered the British army of more than 7,500 troops. Jackson’s men inflicted over 2,000 casualties, while only losing 13 of their own. A strict but popular leader, Jackson earned the nickname “Old Hickory” for his toughness on the battlefield. His heroics in this incident earned him the recognition of Congress and a gold medal.

The famous General returned to serve his country once again in December 1817 during the First Seminole War. Jackson was sent to Georgia to face the Seminole and Creek Indians, as well as prevent runaway slaves from escaping to Spanish Florida. Following a Seminole attack on his Tennessee volunteers, Jackson retaliated by burning their unguarded villages and crops. Jackson found numerous letters proving that the Spanish and British were secretly helping the Indians.

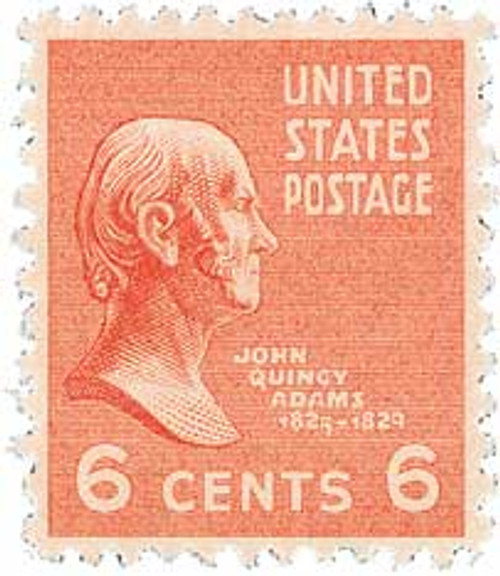

Jackson took control of Pensacola, removed the Spanish governor, and tried and executed two British subjects who had been helping the Indians. Stories of Jackson’s ruthlessness spread through the Seminole tribes and created an international incident. While some found fault with Jackson’s actions, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams supported him and urged Spain to protect or cede the area to the U.S. As a result of Jackson’s actions and Adams’ ultimatum, the U.S. acquired the Florida Territory through the Adams-Onis Treaty. Jackson was rewarded for his heroics and appointed military governor.

Election of 1824

In 1822, the Tennessee Legislature nominated Jackson for President and elected him U.S. Senator. Two years later, the Democratic-Republican Party was the only national political party. The election of 1824 put Jackson against Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, and House Speaker Henry Clay. Although Jackson had the most popular votes, he did not have a majority, so the decision was left to the House of Representatives. Adams was elected President, which Jackson believed was part of a “corrupt bargain” that resulted in Clay’s appointment to Secretary of State.

Election of 1828

The following year, Jackson left the Senate to make a second presidential bid. Again nominated by the Tennessee legislature, Jackson gained the support of John C. Calhoun, Martin Van Buren, and Thomas Ritchie. Van Buren brought back the old Republican Party, renaming it the Democratic Party, with Jackson as their leader. Jackson’s rivals began calling him “jackass,” a name he liked. Although he only used it temporarily, the symbol was later revived when cartoonist Thomas Nast used it for the Democratic Party, and remains its symbol to this day.

Jackson won the election over Adams, but time to enjoy his victory was cut short when his wife Rachel died suddenly on December 22, 1828. Throughout the campaign, Jackson’s rivals had attacked him and his wife for their alleged adultery following their first illegitimate marriage. These accusations took their toll on Rachel, and Jackson believed the stress caused her early death.

Presidency

Jackson’s inauguration was the first presidential inauguration open to the public. The White House was filled with citizens from many classes, standing on chairs to get a glimpse of the man of the people. At one point, many fine White House plates and other items were damaged, and the people were coaxed outside with barrels of drinks.

Without his wife to act as First Lady, Jackson enlisted Rachel’s niece, Emily Donelson, to serve as White House Hostess. In 1834, Emily shared the duties with Sarah Yorke Jackson (wife of Andrew Jackson, Jr.) until Emily’s death in 1836, when Sarah took over all responsibilities. This was the only time in history when two women served as White House hostesses at the same time.

With Jackson’s election as President, a new era in political philosophy was introduced: the Jacksonian Democracy. Jackson aimed to introduce equality for the common man, which he achieved in part by expanding voting rights to include all white male adults, rather than just land owners. This in part helped him achieve his goal of increasing public participation in government. Jackson was also a supporter of Manifest Destiny, the belief that it was America’s destiny to settle the American West, controlling North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Additionally, Jackson planted the seeds for a spoils system in which political appointees were rotated in and out of office, to keep individuals from serving for long periods and possibly corrupting their positions. In 1835, Jackson successfully lowered the federal debt to just $33,733.05, its lowest since 1791.

Another obstacle Jackson faced as President was the Second Bank of the United States. Established in 1816 to help recover from the War of 1812, the national bank was nearing the end of its charter and needed to be renewed. Jackson did not support this, because he felt that it was dangerous to invest all of the country’s money into one bank. The bank also helped the wealthy get richer and was more beneficial to people of northeastern states. Jackson felt the bank made the U.S. government vulnerable to foreign interests. As a result, Jackson successfully vetoed the bank’s request for a re-charter and had all U.S. government funds removed to other banks.

In 1836, Jackson introduced the Specie Circular, requiring people who bought government land to pay in specie (gold or silver coins). The banks did not have enough specie, creating a greater demand that could not be filled. The banks that could not provide the money closed, causing the Panic of 1837, and a depression that lasted for years.

Jackson was also faced with another crisis while in office – the Nullification Crisis or Secession Crisis of 1828-32. Some people believed that high tariffs (the Tariff of Abominations) on European imports made those same goods more expensive than those from the northern states, which raised the prices the southern planters paid. Southerners felt that these high tariffs benefitted northern industrialists while hurting southern farmers. The issue became more complicated for President Jackson when his Vice President, John C. Calhoun, part of the South Carolina Exposition and Protest of 1828, sided with his home state of South Carolina. Calhoun believed that South Carolina had the right to nullify, or declare void, the tariff. In fact, he believed any state had the right to nullify any Federal laws that went against a state’s interests. Jackson was sympathetic to the southern states’ concerns over the fairness of the tariffs, but above all, he believed in a strong Union.

The following year, Calhoun left Jackson’s cabinet and was replaced by Martin Van Buren. Calhoun returned to South Carolina to serve as Senator, and Jackson asked Congress to pass a Force Bill, allowing troops to enter South Carolina to resolve the problem. Jackson told Congress that “The Constitution... forms a government not a league...To say that any State may at pleasure secede from the Union is to say that the United States is not a nation.” When Clay and the protectionists agreed to a Compromise Tariff, they retracted their Nullification Ordinance and the Force Bill was no longer necessary.

One of the most controversial issues of Jackson’s administration was his policy concerning American Indians. While Jackson said it was “unjust to compel the aborigines to abandon the graves of their fathers and seek a home in a distant land,” he also believed that “if they remain within the limits of the States they must be subject to their laws.” In 1830, he signed the Indian Removal Act, giving the President the authority to negotiate the purchase of Indian land in the east in exchange for lands west of the U.S. border.

This legislation was unpopular in the North, but Southerners supported it due to recent discoveries of gold on Cherokee land. A meeting between Cherokee John Ridge and U.S. politicians resulted in the Treaty of New Echota, which many Indians rejected because they did not see Ridge as their leader. Van Buren then sent 7,000 troops to remove the Cherokees, resulting in over 4,000 Cherokee deaths along the “Trail of Tears.” In the end, over 45,000 American Indians were moved west, with the U.S. government purchasing nearly 100 million acres of Indian land plus an additional 32 million acres of western land.

Retirement

In 1837, Andrew Jackson retired to his Nashville home, The Hermitage. Even in retirement, he was an active voice in American politics. He had a large role in both of Martin Van Buren’s presidential campaigns, the first of which Van Buren won. Jackson helped in the acquisition of Texas and was a strong supporter of future President James K. Polk. Jackson died on June 8, 1845, from tuberculosis and heart failure., D.C.