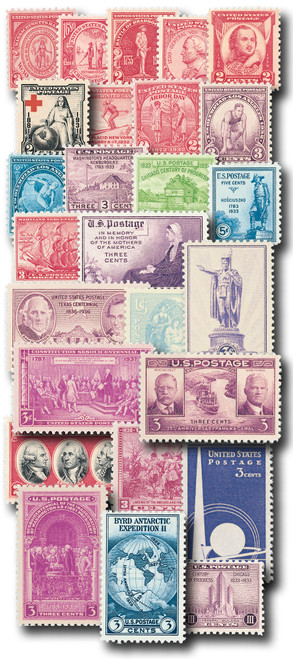

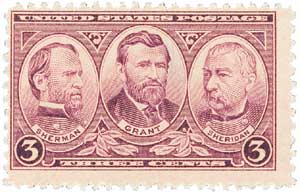

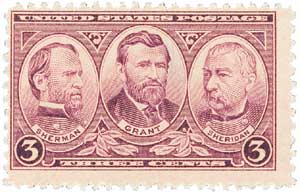

# 782 PB - 1936 3c Arkansas Centennial

1936 3¢ Arkansas Centennial

Issue Date: June 15, 1936

First City: Little Rock, AR

Quantity Issued: 72,992,650

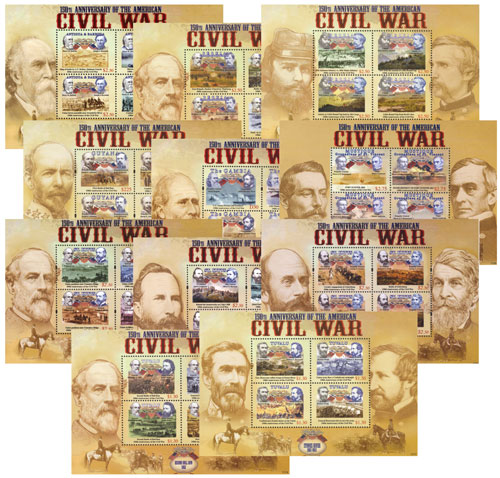

Battle Of Pea Ridge

On March 6, 1862, the largest fight in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Battle of Pea Ridge, began.

The Union Army of the Southwest had pushed the Confederates out of Missouri and were pursuing them into Arkansas in early 1862. Major General Earl Van Dorn had recently taken command of the Southern Army of the West and was determined to regain lost ground. In a letter to his wife, he wrote of his goals saying, “I must have St. Louis.”

Van Dorn was given the opportunity to destroy the much smaller Union Army when Brigadier General Samuel Curtis positioned his men near Pea Ridge in northern Arkansas. Van Dorn’s plan was to march around the enemy and attack their rear from the North, cutting off their supply route and communications. The Union would be forced to retreat to Missouri or be destroyed.

General Van Dorn split his forces into two divisions, which would travel along either side of Pea Ridge and attack the Union on two fronts. He instructed his soldiers to take rations for three days, forty rounds of ammunition, and a blanket. The supply trains would carry ammunition for the cannon and an additional day’s rations. The Army of the West headed out for a hard three-day march in a freezing storm and arrived near the Union position on March 6, 1862. That night, Van Dorn ordered an attack on the Union line at Elkhorn Tavern, and they succeeded in pushing the Union forces back and cutting the Union lines of communication before the night was out.

Van Dorn put Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch in charge of the divisions that turned east to meet the Union Army. The Northern forces detected their movements and were ready for them. The two sides met in the small town of Leetown.

Union cavalry units attacked in order to buy some time for the Union infantry to organize. The much larger Confederate force overwhelmed the small force and captured their artillery. By that time, the Federal artillery line was in place and began firing on the Rebel troops.

General McCulloch rode forward to scout the enemy’s position and was killed by enemy fire. Brigadier General James McIntosh took command, but he soon met the same fate. The next in the chain of command was Colonel Louis Hébert. The other units pulled back from the attack and awaited orders from Hébert. He did not realize his superiors were dead and that he was in command.

Hébert led his division in an attack from the left and overtook the Union’s Third Division, led by Colonel Jefferson C. Davis (no relation to the Confederate president). The Confederate troops were eventually surrounded on three sides and retreated in confusion. Hébert and his men got lost in the battle’s smoke and were captured. Some of the troops were left on the field, others returned to camp, while the rest connected with the other division of the Confederate Army.

While a portion of each army was occupied in Leetown, the rest were fighting to the north at Elkhorn Tavern. The Confederate force was considerably larger than their opponents, but the Union held a stronger defensive position on top of Pea Ridge.

The morning began with the sound of artillery fire. The Southern guns outnumbered the Federal cannon and cleared the way for an infantry advance. General Sterling Price led the attack up the hill and was met by Colonel Eugene Carr and his regiment. In spite of gaining reinforcements, the Union was still outnumbered and was forced back up the hill. Carr was wounded three times but continued to lead his men in the field.

The Confederates were gaining ground when the Union began a short counterattack at 6:30 p.m. The Northern soldiers were soon called back because of darkness.

Preparations for the next day’s battle took place that night. The Union forces consolidated near Elkhorn Tavern, and Curtis made sure his men were fed, resupplied with ammunition, and rested during the night. Van Dorn was joined by the remainder of the forces that had fought at Leetown but went without food or additional ammunition because the supply wagons had been mistakenly sent back to camp.

The sound of cannon fire again greeted the dawn. This time the Union had more artillery. The Confederate gunners were forced back, and the Federal guns were turned toward the surrounding woods. Splinters from the trees and rocks from the surrounding mountainside added to the deadly barrage of cannonballs.

The Union attacked the Confederates from many sides. By about 9:30 a.m., Van Dorn realized his supply train had gone in the opposite direction from the battle and he had no hope of victory. The Army of the West began a rapid and disorganized retreat. They escaped capture but had missed the opportunity to overcome a much smaller Union force.

The Federal victory at Pea Ridge ensured that Missouri would remain a part of the Union. Northern Arkansas also remained under Union control. Brigadier General Curtis hoped to capture Little Rock, Arkansas, but the town proved to be too far from supply lines and well protected by guerrilla fighters. He seized Helena though, a few months later.

Many of the Confederate troops deserted during the retreat. Those from Missouri returned home, the Native Americans vanished into the woods, and other soldiers sought refuge in Arkansas. Van Dorn was disheartened from the loss and transferred his remaining forces east of the Mississippi River to support the Army of Tennessee.

1936 3¢ Arkansas Centennial

Issue Date: June 15, 1936

First City: Little Rock, AR

Quantity Issued: 72,992,650

Battle Of Pea Ridge

On March 6, 1862, the largest fight in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, the Battle of Pea Ridge, began.

The Union Army of the Southwest had pushed the Confederates out of Missouri and were pursuing them into Arkansas in early 1862. Major General Earl Van Dorn had recently taken command of the Southern Army of the West and was determined to regain lost ground. In a letter to his wife, he wrote of his goals saying, “I must have St. Louis.”

Van Dorn was given the opportunity to destroy the much smaller Union Army when Brigadier General Samuel Curtis positioned his men near Pea Ridge in northern Arkansas. Van Dorn’s plan was to march around the enemy and attack their rear from the North, cutting off their supply route and communications. The Union would be forced to retreat to Missouri or be destroyed.

General Van Dorn split his forces into two divisions, which would travel along either side of Pea Ridge and attack the Union on two fronts. He instructed his soldiers to take rations for three days, forty rounds of ammunition, and a blanket. The supply trains would carry ammunition for the cannon and an additional day’s rations. The Army of the West headed out for a hard three-day march in a freezing storm and arrived near the Union position on March 6, 1862. That night, Van Dorn ordered an attack on the Union line at Elkhorn Tavern, and they succeeded in pushing the Union forces back and cutting the Union lines of communication before the night was out.

Van Dorn put Brigadier General Benjamin McCulloch in charge of the divisions that turned east to meet the Union Army. The Northern forces detected their movements and were ready for them. The two sides met in the small town of Leetown.

Union cavalry units attacked in order to buy some time for the Union infantry to organize. The much larger Confederate force overwhelmed the small force and captured their artillery. By that time, the Federal artillery line was in place and began firing on the Rebel troops.

General McCulloch rode forward to scout the enemy’s position and was killed by enemy fire. Brigadier General James McIntosh took command, but he soon met the same fate. The next in the chain of command was Colonel Louis Hébert. The other units pulled back from the attack and awaited orders from Hébert. He did not realize his superiors were dead and that he was in command.

Hébert led his division in an attack from the left and overtook the Union’s Third Division, led by Colonel Jefferson C. Davis (no relation to the Confederate president). The Confederate troops were eventually surrounded on three sides and retreated in confusion. Hébert and his men got lost in the battle’s smoke and were captured. Some of the troops were left on the field, others returned to camp, while the rest connected with the other division of the Confederate Army.

While a portion of each army was occupied in Leetown, the rest were fighting to the north at Elkhorn Tavern. The Confederate force was considerably larger than their opponents, but the Union held a stronger defensive position on top of Pea Ridge.

The morning began with the sound of artillery fire. The Southern guns outnumbered the Federal cannon and cleared the way for an infantry advance. General Sterling Price led the attack up the hill and was met by Colonel Eugene Carr and his regiment. In spite of gaining reinforcements, the Union was still outnumbered and was forced back up the hill. Carr was wounded three times but continued to lead his men in the field.

The Confederates were gaining ground when the Union began a short counterattack at 6:30 p.m. The Northern soldiers were soon called back because of darkness.

Preparations for the next day’s battle took place that night. The Union forces consolidated near Elkhorn Tavern, and Curtis made sure his men were fed, resupplied with ammunition, and rested during the night. Van Dorn was joined by the remainder of the forces that had fought at Leetown but went without food or additional ammunition because the supply wagons had been mistakenly sent back to camp.

The sound of cannon fire again greeted the dawn. This time the Union had more artillery. The Confederate gunners were forced back, and the Federal guns were turned toward the surrounding woods. Splinters from the trees and rocks from the surrounding mountainside added to the deadly barrage of cannonballs.

The Union attacked the Confederates from many sides. By about 9:30 a.m., Van Dorn realized his supply train had gone in the opposite direction from the battle and he had no hope of victory. The Army of the West began a rapid and disorganized retreat. They escaped capture but had missed the opportunity to overcome a much smaller Union force.

The Federal victory at Pea Ridge ensured that Missouri would remain a part of the Union. Northern Arkansas also remained under Union control. Brigadier General Curtis hoped to capture Little Rock, Arkansas, but the town proved to be too far from supply lines and well protected by guerrilla fighters. He seized Helena though, a few months later.

Many of the Confederate troops deserted during the retreat. Those from Missouri returned home, the Native Americans vanished into the woods, and other soldiers sought refuge in Arkansas. Van Dorn was disheartened from the loss and transferred his remaining forces east of the Mississippi River to support the Army of Tennessee.