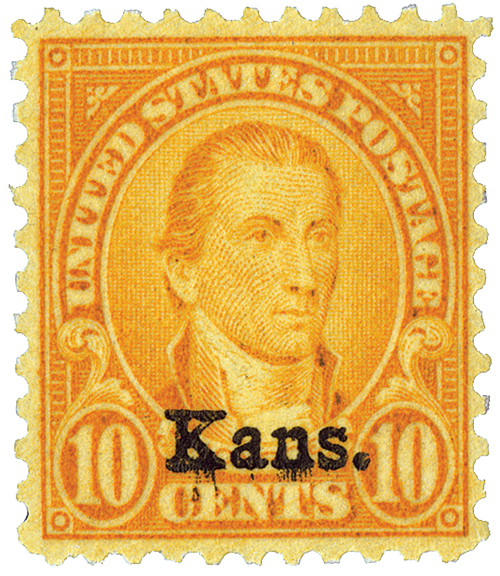

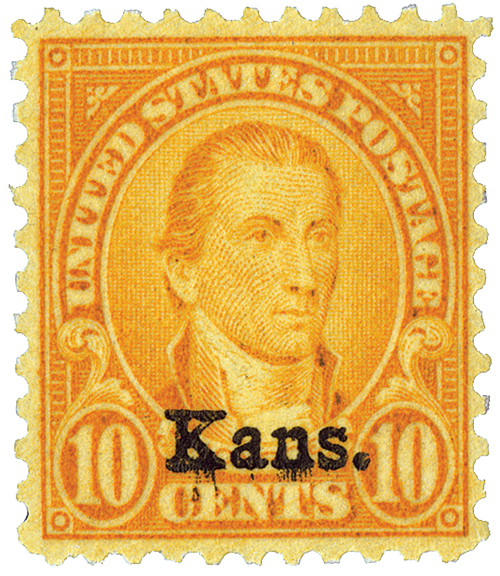

# 668 PB - 1929 10c Monroe, orange yellow, Kansas-Nebraska overprints

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

10¢ Kansas

First City: Colby, KS

Quantity Issued: 2,860,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Orange yellow

Kansas Becomes 34th State

Four main tribes lived in eastern Kansas before white settlers arrived – the Kansa, Osage, Pawnee, and Wichita. After acquiring horses by the late 1700s, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and other tribes moved into the central plains to hunt buffalo.

Spanish explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led the first whites into the area in 1541. Coronado’s expedition was looking for a land called Quivira, where an Indian guide told him he would find gold. No gold was found, and the Spanish left without creating a settlement. By the early 1600s, France had claimed much of North America, including Kansas. During the early 1700s, French fur trappers began to settle in what is now the northeastern corner of Kansas.

In 1803, France sold the vast Louisiana Territory to the United States, including most of Kansas. The southwestern corner of present-day Kansas was claimed by Spain. This land would later become part of Mexico, and then Texas, before being made part of Kansas.

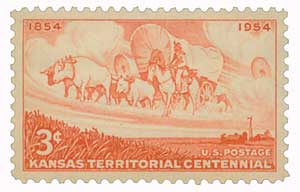

Kansas was governed as part of the District of Louisiana, the Louisiana Territory, and the Missouri Territory. Many Indians from the East were resettled in Kansas for a time. But soon, whites began to settle the area. Some came as missionaries to the Indians and others decided to stay while traveling the Santa Fe Trail. In 1827, Colonel Henry Leavenworth opened the first U.S. outpost, Fort Leavenworth. By 1850, there was substantial pressure to open Kansas for white settlement. The Federal Government negotiated with Indians and reclaimed most of the land. In 1854, Kansas was declared open for settlement. The Indians were sent to reservations in Oklahoma – but some decided to fight. However, none of these groups were successful for long.

During the 1850s, Kansas became the center of the America’s fight over slavery, an issue which had divided the nation. In Congress, slavery created a deep rift between the North and South. This was particularly true concerning the fate of new U.S. territories – there was a great struggle over whether the practice of slavery would be allowed in the new territories or not. Congress sought to avoid the issue with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which essentially let the people who settled these territories decide whether slavery would be legal or not.

Kansas became a U.S. territory on May 30, 1854. Soon, settlers from the North and South were pouring into Kansas. Groups looking to influence the decision over slavery aided these people in an attempt to gain a majority. In the election of 1855, many citizens from the slave state of Missouri came to Kansas and voted. Proslavery candidates did well in the election. Soon after, violence broke out in Kansas, particularly near the border with Missouri. The fighting became so intense that newspapers began to call the territory “Bleeding Kansas.” Proslavery officials wrote a constitution favoring slavery, but Congress refused to admit Kansas to the Union as a slave state. Finally, politicians opposed to slavery were able to gain control of the legislature.

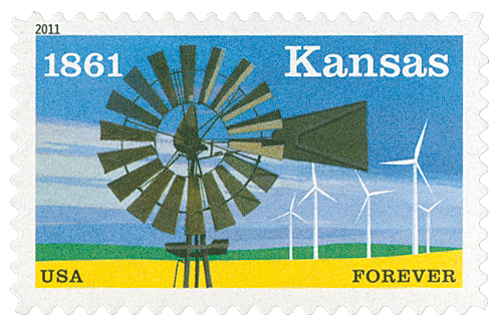

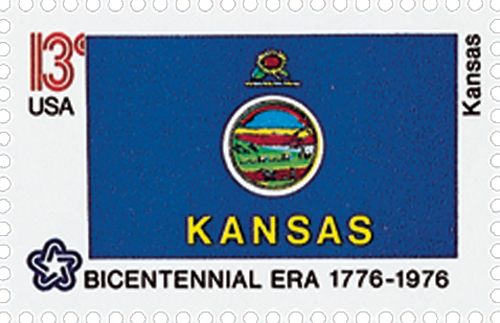

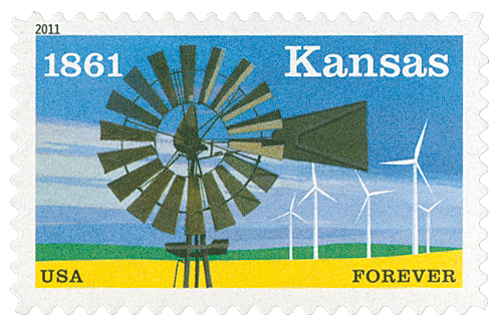

Kansas achieved statehood on January 29, 1861. At that time, several Southern states had already seceded from the Union. Within a few weeks, the Civil War erupted. Kansas was soon hit with a new wave of violence. Confederate raiders under William C. Quantrill burned most of the town of Lawrence, Kansas, and killed about 150 people. During the war, Kansas sent more men to the Union Army in proportion to its total population than any other state. When the war ended in 1865, thousands of Union veterans and newly freed slaves moved to Kansas. In the years following the war, Kansas became a major ranching and farming center (dubbed the Breadbasket of America). Water shortages have plagued the state, though, particularly during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.

1929 Kansas-Nebraska Overprints

10¢ Kansas

First City: Colby, KS

Quantity Issued: 2,860,000

Printing Method: Rotary Press

Perforation: 11 x 10.5

Color: Orange yellow

Kansas Becomes 34th State

Four main tribes lived in eastern Kansas before white settlers arrived – the Kansa, Osage, Pawnee, and Wichita. After acquiring horses by the late 1700s, the Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, Kiowa, and other tribes moved into the central plains to hunt buffalo.

Spanish explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado led the first whites into the area in 1541. Coronado’s expedition was looking for a land called Quivira, where an Indian guide told him he would find gold. No gold was found, and the Spanish left without creating a settlement. By the early 1600s, France had claimed much of North America, including Kansas. During the early 1700s, French fur trappers began to settle in what is now the northeastern corner of Kansas.

In 1803, France sold the vast Louisiana Territory to the United States, including most of Kansas. The southwestern corner of present-day Kansas was claimed by Spain. This land would later become part of Mexico, and then Texas, before being made part of Kansas.

Kansas was governed as part of the District of Louisiana, the Louisiana Territory, and the Missouri Territory. Many Indians from the East were resettled in Kansas for a time. But soon, whites began to settle the area. Some came as missionaries to the Indians and others decided to stay while traveling the Santa Fe Trail. In 1827, Colonel Henry Leavenworth opened the first U.S. outpost, Fort Leavenworth. By 1850, there was substantial pressure to open Kansas for white settlement. The Federal Government negotiated with Indians and reclaimed most of the land. In 1854, Kansas was declared open for settlement. The Indians were sent to reservations in Oklahoma – but some decided to fight. However, none of these groups were successful for long.

During the 1850s, Kansas became the center of the America’s fight over slavery, an issue which had divided the nation. In Congress, slavery created a deep rift between the North and South. This was particularly true concerning the fate of new U.S. territories – there was a great struggle over whether the practice of slavery would be allowed in the new territories or not. Congress sought to avoid the issue with the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which essentially let the people who settled these territories decide whether slavery would be legal or not.

Kansas became a U.S. territory on May 30, 1854. Soon, settlers from the North and South were pouring into Kansas. Groups looking to influence the decision over slavery aided these people in an attempt to gain a majority. In the election of 1855, many citizens from the slave state of Missouri came to Kansas and voted. Proslavery candidates did well in the election. Soon after, violence broke out in Kansas, particularly near the border with Missouri. The fighting became so intense that newspapers began to call the territory “Bleeding Kansas.” Proslavery officials wrote a constitution favoring slavery, but Congress refused to admit Kansas to the Union as a slave state. Finally, politicians opposed to slavery were able to gain control of the legislature.

Kansas achieved statehood on January 29, 1861. At that time, several Southern states had already seceded from the Union. Within a few weeks, the Civil War erupted. Kansas was soon hit with a new wave of violence. Confederate raiders under William C. Quantrill burned most of the town of Lawrence, Kansas, and killed about 150 people. During the war, Kansas sent more men to the Union Army in proportion to its total population than any other state. When the war ended in 1865, thousands of Union veterans and newly freed slaves moved to Kansas. In the years following the war, Kansas became a major ranching and farming center (dubbed the Breadbasket of America). Water shortages have plagued the state, though, particularly during the Dust Bowl of the 1930s.